Between around 2012 and 2017, Rob Halpern was in the UK every summer, and during this time he gave an extraordinary series of readings, in Brighton, Cambridge, London, whose echoes still sometimes crash off the walls with a kind of plangent whisper. Lisa Jeschke

memorably characterised one of these readings as lasting so long that it felt as if if it still hadn't ended. “In some ways it still hasn’t”, she observed, and this wasn’t really a joke. The reading in question took place at the Sussex Poetry Festival in summer 2013, held in the upstairs room of a pub next to Brighton station, where the shutters could be closed so that none of the sunlight from outside entered into the room, a kind of all-day poetry cocoon. Lisa Robertston read—I think—the whole of

Cinema of the Present and Rob read a substantial portion of

Music for Porn (or perhaps it was

Common Place): two very different poetries, two entire worlds, poetics that engage with a kind of world-building, an attempt to map a totality—in the case of

Cinema of the Present, in a luxuriant, sentence-based structure, in that of

Music for Porn, a mixture of poetry and prose that curls in on itself with an agonised and painful rigour that at once collapses and extends the distances and costs of the so-called War on Terror. Though they were the ‘headliners’, both poets read well beyond the expected length, around an hour each; it was excessive,

too long, too much—and it was thus precisely right for each of the projects and the way they move into and out of the world, pushing at the limits of what we can hear. Like Lisa J said, the reading still hasn’t ended.

During this time, Rob was working through the project encompassing

Common Place,

Music for Porn, and their refraction in the UK collection

Placeholder: a difficult project which is a work of mourning—for the victims of US neo-imperialism after 9/11, for the loss of a lover that the work can barely begin itself to articulate—a ritualistic, repetitive, masturbatory one conducted through an eroticized register that, in the wake of Genet, Whitman, and New Narrative writing, drags us through the contemporary necropolis with a tenderness that’s at once deliberately repulsive and full of loving care. In their ability to convey a kind of ambient, immersive detail in the minutiae of horrific documents of the abuses of power, combined with a devastating queer erotics of mourning and loss, along with Rob's patient, slow, careful, sometimes agonising delivery, those readings were a vitalizing force—at once rigorously Marxist, queer, and committed, through a verse line sometimes knottily prosaic in its unfolding and a prose line verse-like in its lyrical concatenations, its devotional circulations. (The impact of that work on a transatlantic poetic community—or, perhaps more accurately, several intersecting communities--can be illustrated by the special

Crisis Inquiry volume of

Damn the Caesars that Richard Owens edited around this time, jointly dedicated to the work of Halpern and Keston Sutherland). Since

Placeholder, Rob’s work has moved on, even as the formal features and many of the thematic concerns remain: in 2017, a veer pamphlet called

Touching Voids in Sense came out with little fanfare, but was, for me, one of Halpern’s finest achievements, its amped-up play with sound, a rhyming insistence sometimes deliberately verging on doggerel, suffusing a painful reckoning with that personal loss the previous work had skirted around, via meditations on a photography by Mike Kelley reproduced on the cover; and then last year (though written earlier), came

Fertility, published by Sara Crangle and Sam Ladkin’s Sancho Panzo press, a set of love poems with the characteristic reflexive torque of Halpern’s verse, but with a lighter tone—one might almost call them

charming, something that could hardly be said of the preceding

Music for Porn-Common Place Inferno.

Now comes Halpern’s latest. The 28 poems that make up

Hieroglphys of the Inverted World, none longer than two pages, were written, as Halpern notes in the book’s long afterword, in the atmosphere of the far right rallies

at Charlottesville in 2017, through the period extending into the moment of corona crisis in 2020. As such, they function as something of a failed daybook, a stop-start diary full of gaps, ellipses pauses or smoothed-over transitions, like the rub of imperfectly-sanded wood, the visible superglue on broken plastic or metal, the Polyfilla on the crack in the wall. The book’s title, and its explanation in the afterword, ‘For a Hieroglyphic Poetics’, refigure such fractured “calendrics” through a kind of after-the-fact schematisation by which discrete lyrics are joined into the coherent incoherence of a book. Both the hieroglyphs and the inverted world are Marx’s terms for the operations of capital, the structural prism in and through which the world is viewed upside down, the most ‘unnatural’ and distorted of social relations enshrined as the norm.

Value, therefore, does not stalk about with a label describing what it is. It is value, rather, that converts every product into a social hieroglyphic. Later on, we try to decipher the hieroglyphic, to get behind the secret of our own social products; for to stamp an object of utility as a value, is just as much a social product as language.

(In today’s climate this process gets once more concealed under that murderously snappy slogan “the new normal”; but it is better understood as what

Adorno, half-a-century before, called “the heritage of the ancient spell—the new form of the myth of the ever-same”.)

A poem is, Halpern suggests, both a good and a bad place to figure “the narrow path of the totality”. Within the frame of the poem, and if one is not

Zukofsky attempting to set Marx to Cavalcanti, poems have tendency to evade their concepts, either too light or too blunt a hammer for the task; and if, as per Marx, the Hegelian dialectic must in turn be “inverted”, turned right side up, the rush of blood streaming down the body when one spends too long standing on one’s head risks its own kind of hallucinatory distortion. Yet it is this impulse that, as C

ésaire observed of Lautr

éamont, that also gives poetry is particular brand of (sur)realism in chronicling that “inverted world”; and in the past few years of imperial afterlives as much as the era of 19th century imperialism, such distortions more than match the distorted world around. Consequently, a real Baudelarian spleen, new to Halpern’s work, suffuses the anti-Fascist fury of some of the earlier poems: “in my tongue-torqued tuna-slag the fascists are totally fucked / They puke their boiled prawns on my dream of corn & fat” (13) writes Halpern, insisting on his right “to smother / [fascists] in their own puke” while sarcastically observing “they fashion the worst haircuts too” (22). Later poems become less gleeful, more mournful, as Halpern (re)turns to the bloody viscera familiar from his earlier work: the victims of bombings and torture spread out across a landscape at once real and imagined, in which “common sense” and “

common place” are distorted echoes as akin to black sites where torture, erasure and incarceration underwrite whatever script’s read out on the evening news or the propaganda of official verse, official statistic, official silence. Here Halpern reiterates the concerns of his previous work with deliberate obsessiveness for which rhyme’s absurd recurrence forms a useful figure (more on that presently):

homonationalism, the war on terror, the unspeakable trauma of the AIDS crisis, personal loss, the rising inequalities of a hometown—San Francisco—in which the tech boom, the opioid crisis, homelessness, the radical alteration of the city’s social landscape index the changing structure through which the wealthier realms of the ‘western world’ view life as such—the screens of social media, their bases a few miles away from where Halpern might write the poem.

Building on Halpern’s tutelary immersion in New Narrative writing, much of his previous work sees the erotic as the primary valence through which such concerns are figured, from the radically compromised devotional erotics of

Music for Porn and

Common Place and their

Genet-ian love poems to the dead, the beautifully bungled, self-sabotaging love poems in the chapbook

Fertility. That’s perhaps less the case in these

Hieroglpyhs, where the erotic occurs alongside a broader range of dedications—to Halpern’s daughter, Laia-Rose, to his late father, to Sean Bonney and to Andrea Brady—and on less programmatic lines. Yet Halpern nonetheless continues to borrow from the erotic and more-than-erotic methodologies of the Romantics and the Metaphysical poets in particular. As he suggests in the afterword,

via Anahid Nersessian’s recent

The Calamity Form, these are poets whose approach to the collapsed distances of simile, metaphor, rhyme, and other forms of metonymy reproduce the changing scalar dimensions of the growth of racial capitalism, from the initial colonial moments of the Early Modern era and its extensions into the Americas, to the growth of the Industrial Revolution and the Atlantic expansion of the triangular trade. Like these emergent and expanding forms of capital, the conceit, wordplay and wit, maintain multiple dimensions at once, at once an expansion and a compression, or what Halpern might, in today’s terms, name “a ‘kill box’ collapsing space [...] the interior of a prison cell like another hoary figure for the soul” (38).

This receives perhaps its clearest expression in one of the longer poems in the book, Halpern’s elegy-cum-verse essay, “for & after” Sean Bonney:

Counterfeiting stones to rhyme with what I can’t even hear

Inaudible substance of catastrophe a heavy-handed conceit

[...]

like the soul

In Donne’s Funerall where the poet compares his to a wreathe

Of braided hair laced round his lover’s shrouded writs

Confusing the spirit that inspires his verse with a cuff

Or cop-lock affirming the vehicle’s power to collapse mystery. (36)

For Halpern, as in Donne, this metaphysical collapse maps the image of the beloved, of fulfilled or frustrated desire, onto the cartographic extensions and concealments of imperialism and its mirrors in a language which enables and justifies—or at least normalises, renders into common sense—this movement. (Again, that naming and renaming of conquered territory, “the names of occupied places & lands / And how each enlarges a colony”.) Here are some of those cartographies: constantly recurring images of body parts and the desires they arise juxtaposed with the tortured bodies and corpses of the War on Terror and the occupation of Palestinian lands: the erasure from maps and physical locations of dwellings, which, raised according to Zionist tenets, Halpern “was told as a kid / never existed as places” (26); the bones of buried Palestinians ground up to simulate the sands of a beach in Ramallah (27); the victims of drone strikes or the wounded soldiers of occupying armies juxtaposed with Halpern’s interactions with his one-year old daughter; the poet writing the poem alongside the workers in Shenzen or Ghuangzho (20) who produce the earpieces and computer devices he uses to communicate internationally or the clothes he wears, in a parody of globalisation’s distances, at once collapsed through technologically-advanced commodities and radically extended through the gap between Global North and Global South.

For Halpern: “What appears to be the most obvious of things—be it the self-evidence of everyday life, or the social violence erased in that self-evidences—arrives dispossessed of a language not already structured by the violence it might wish to oppose or decry” (49). The aim, then, is not a revelation of a tenderness that might outstrip such conditions—a tenderness that reaches its parodic peak in Halpern’s images of erotic fantasy and commune with the corpses of US soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan and of Guantanamo Bay detainees in Music for Porn and Common Place—but of the inextricability of a language of love, desire, tenderness and care from the structural conditions in which these affects are produced. For Halpern, the poem thus evinces a kind of Marxist version of “negative capability” challenging the irritable facts and reasons of what passes for common sense in the “inverted world” where unequal social relations are reified as normality, where abstraction of value and the commodity form is the ground on which relations from the most minute to the largest are conducted; “whose unspeakable aim might be to abolish its own conditions, something the poem is only ever too frail to do” (57). Poetry is at once both the ideal site for such analysis and something which, precisely because it moves beyond the analysis of diagnostic, prosaic language, gestures beyond itself and beyond the social conditions which produce it and in which it is produced: “In other words, diagnosis of our conditions always lies elsewhere [...] the poem’s competence is [...] as a point of departure [...] a move beyond the poem, out of poetry, headlong & recklessly into the world” (57).

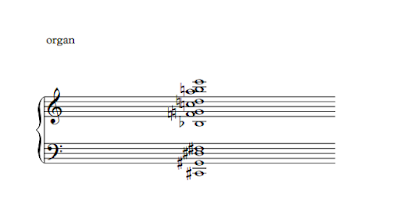

In metaphor, simile, and other forms of conceit, one thing stands for another thing, but they don’t line up as do the balanced parts of an equation or a fraction, the components of a sum. Relatedly, in its play with various forms of rhythmic counting, parallelism, the numbered parcelling out of syllables and other particles of sound, poetry may gesture at mathematics, but it lacks the forms of closure, or even the paradoxical logics of set and chaos theory. Likewise, it may gesture at music, but a music that’s lost the flow of sound, one which is blocked and dammed by the stumbling block of word on page (or perhaps vice versa). These paradoxes and double-binds—which are not, perhaps, fully-formed dialectics—once more for Halpern find their expression in the titular figure of the hieroglyph, taken both, as we’ve seen, from Marx, and from

Johann Wilhem Ritter via Walter Benjamin (with Etel Adnan’s

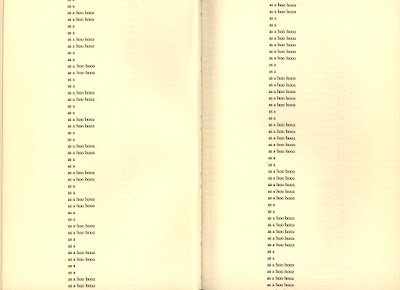

Arab Apocalypse ever in view). For Ritter, Halpern suggests, the hieroglyph is a sign that stands in for sound, a fixed mark that stands in for movement, a compressed point that contains a kind of transparent secret, were we to know how to read it, and the book’s cover design incorporates fragments Ritter’s sound diagrams, cut in half by the spine. The hieroglyph is thus a useful jumping-off point for the way these poems work with sound. “Purposeless rhymes mute forgotten / Crimes” (38), Halpern writes in the poem dedicated to Sean Bonney; or again, in the following poem, for Andrea Brady: “I think of the names of occupied places & lands / And how each enlarges a colony as if the word / Itself were a spit of sand in my mouth” (39). At times, sound forms an alternative way of knowing. In the same poem, Halpern notes his daughter Laia-Rose’s imitation of a seagull on the beach, “soaring in some divine imitation she soars the air / Parts as it would for a word like ‘bird’ it brings / Her closer to the world its creatures & mysteries” (39)—for the moment, a counter-possibility to the colonial mimesis, its naming and renaming of erased place names, redrawn borders on the map, from Afghanistan to Palestine, which occupies the rest of the poem. Likewise, in the concluding poem, ‘Hieroglyph No.11520’, dedicated to Laia-Rose, Halpern recalls the recitation of Delmore Schwartz’s ‘I Am Cherry Alive, The Little Girl Sang’ to his daughter during the first year of her life as a daily ritual. Here, poetry—particularly the jingling sonic pleasure of rhyme—is lullaby, balm and joyous invention, with “not one rhyme excluded” (45), “as if truth / Were hiding in some alphabetic trance where it reaches us / Thru a veil this screen of rhymes” (46). But a poem cannot include every rhyme, and rhyme’s infinity forms a clanging bad metaphor for the impossibility of imagining elsewhere, a perpetual echo to narcissus’ ever-same, the poem a mirror to nature only in that nature’s ‘self-evidence’ is that of the totalising sphere of global racial capitalism, with all its extractivist terror.

Ultimately, then, the rhyme, the conceit, the metaphor, the simile, and all those forms of heightened language contained with the serial cell of the poem recur as a repeated, and traumatic re-staging of the poem’s own failure to grasp and encompass the common sense and common place it seeks:

This model falls flat the conceit’s useless

To do anything more than what poetry has always done

To arouse the ache for communion or the rage that joins

Its loss [.] (37)

To many readers, this aroused ache will hardly seem “useless”: “To arouse the ache for communion or the rage that joins / Its loss” is surely as good a slogan or a programme for poetry as any, even as it within its very form is staged that collapse, that breaking apart so central to the book, easing as it does into iambics before the polysyllables of “communion” break it apart, extending into the line break between ‘joining’ and ‘loss’ that contradictions its very urge for communion or joining with their opposites. This double movement—that of utopian assertion and formal negation—doesn’t so much cancel out as further the project of deciphering the hieroglyphs that surround us, reading the unreadable, in aching rage against the losses the daily we hide from and are hidden from us. In doing so, the ache and the rage of Halpern’s verse trace a music intensely moving in its repeated commitment: “To exceed its limit in a movement beyond the shattered sight of glass: to conceive what’s inconceivable as part of a larger effort to abolish the conditions of that impossibility” (59).