(Some thoughts on three recent concerts as spring gradually emerges...)

Claire Chase presents Pauline Oliveros, part of SoundState, Queen Elizabeth Hall Foyer, 3rd April 2022

This free concert in the foyer of the Queen Elizabeth Hall paid tribute to the late Pauline Oliveros, exemplifying the social, and sonic pleasures of the late composer’s work. Playing an array of flutes and whistles, Claire Chase was accompanied by Senem Pirler, working with the electronic ‘Expanded Instrument System’, a “computer-controlled sound interface” Oliveros first designed in 1963. For the first piece, ‘Sounds from Childhood’ (1992), Chase instructed the audience to remember a time in childhood “when it was a lot of fun to make sounds”, and then to make those sounds. The collective texture—raspberries, sighs, groans, ululations—was then played back through the EIS as a chorus at once disjointed and with the pleasures of togetherness; memory taken forward into the present and, via the EIS, the futuristic. For the text score ‘13 Changes’ (1988), Chase read out each of the textual prompts before interpreting them for an array of flutes. The titles thus served as entities in themselves, by terms pithy, humorous, and thought-provoking, from ‘Songs of ancient mothers among awesome rocks’ to ‘Rollicking monkeys landing on Mars’. The EIS gave the resultant whirling of breath and air an edge sometimes mechanical, sometimes digital, the pieces rendered something like epic bagatelles, condensed but imaginatively vast and expansive.

The duo concluded with the most substantial work on the programme, ‘Intensity 20.15, Grace Chase’ (2015). Oliveros wrote the piece for Chase’s enormous bass flute—or ‘Bertha’, as she dubs it—but with the kicker that the flute would only be deployed briefly at the end. For the rest of the piece, Chase would have to find other sound-producing means. After extended discussion, Oliveros and Chase hit upon the idea of using texts by Chase’s grandmother, Grace. Diagnosed as schizophrenic in her 20s and subjected to electroshock, Grace had self-medicated through art, writing unclassifiable texts in hundreds of notebooks, their inveterate punning subverting linguistic and patriarchal authority.

“In adulthood I have taken up a load of childlike things”, Chase proclaimed, neatly inverting the Biblical declaration of maturity. She proceeded to unload carrier bags of notebooks, bells, whistles, and percussion instruments, turning the stage into a kind of children’s music workshop run riot. This was music as dispersed play rather than concentrated training, un-learning the hierarchies embedded in the world of ‘classical’ music. A linguistic riff—“And I step on you and you and you”—saw Chase using countless pairs of shoes as percussion instruments, ultimately striking a giant bass drum with a high heel in a neatly subversive feminist gesture. The piece ended with an extended bass flute drone, a meditation that eased us back into the present. Throughout, the legacies of the women Chase described as her spiritual grandmother (Oliveros) and her biological grandmother (Grace) provided a non-essentialist model of feminist energies, accessible to all: airing what was unaired in order to bring in new airs for us to breathe together.

A few minutes in, I overheard a small child in the row behind me whisper: “this is cool, I’d actually like to stay”. The ‘avant-garde’ or ‘experimental’ here is accessible, not despite, but precisely because of its experimentation, the particular openings it offers onto the world—to childhood and adulthood, to suppressed memories and lost histories—and above all, to the sheer pleasure in sound-making as participatory endeavour. Oliveros would have been proud.

The duo concluded with the most substantial work on the programme, ‘Intensity 20.15, Grace Chase’ (2015). Oliveros wrote the piece for Chase’s enormous bass flute—or ‘Bertha’, as she dubs it—but with the kicker that the flute would only be deployed briefly at the end. For the rest of the piece, Chase would have to find other sound-producing means. After extended discussion, Oliveros and Chase hit upon the idea of using texts by Chase’s grandmother, Grace. Diagnosed as schizophrenic in her 20s and subjected to electroshock, Grace had self-medicated through art, writing unclassifiable texts in hundreds of notebooks, their inveterate punning subverting linguistic and patriarchal authority.

“In adulthood I have taken up a load of childlike things”, Chase proclaimed, neatly inverting the Biblical declaration of maturity. She proceeded to unload carrier bags of notebooks, bells, whistles, and percussion instruments, turning the stage into a kind of children’s music workshop run riot. This was music as dispersed play rather than concentrated training, un-learning the hierarchies embedded in the world of ‘classical’ music. A linguistic riff—“And I step on you and you and you”—saw Chase using countless pairs of shoes as percussion instruments, ultimately striking a giant bass drum with a high heel in a neatly subversive feminist gesture. The piece ended with an extended bass flute drone, a meditation that eased us back into the present. Throughout, the legacies of the women Chase described as her spiritual grandmother (Oliveros) and her biological grandmother (Grace) provided a non-essentialist model of feminist energies, accessible to all: airing what was unaired in order to bring in new airs for us to breathe together.

A few minutes in, I overheard a small child in the row behind me whisper: “this is cool, I’d actually like to stay”. The ‘avant-garde’ or ‘experimental’ here is accessible, not despite, but precisely because of its experimentation, the particular openings it offers onto the world—to childhood and adulthood, to suppressed memories and lost histories—and above all, to the sheer pleasure in sound-making as participatory endeavour. Oliveros would have been proud.

Eva-Maria Houben / GBSR Duo, Together on the Way', Southbank Centre, 3rd April 2022

(Image again by Gillian Moore)

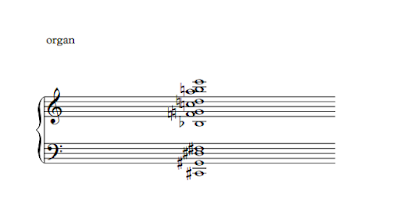

Immediately preceding the Oliveros concert in the foyer, the QEH's inner concert hall saw a performance by the composer and the GBSR Duo, of Eva-Maria Houben's Together on the Way for organ, piano, and percussion, premiered at Huddersfield in 2021, a performance recently released on Another Timbre. Whereas that performance took place in a small church, the expanded space of the QEH allowed the work to breathe in a new way, even as so much of Houben's music is about doing away with hierarchies of vast auditoriums, prosceniums, scale as a performance of cultural legitimacy: a case outlined in her book Musical Practice as a Form of Life and elsewhere, which might in part be about returning to a pre-19th century way of thinking--the tradition of the local church organist, say (Houben's first professional job in music was as a 12-year old church organist), a different relation between composer, performer, and listening community than that of the giant concert hall--as well as elements of 19th-century Romanticism that might be reclaimed beyond the idea of the Romantic composer as an isolated, bourgeois "political bonehead". Breathing in a new way, cast in a different light.

Today, bathed in a resplendently subtle light show, Houben was playing the QEH organ that literally rises from underneath the stage (sadly not a spectacle the audience got to witness): emergence from the depths not so much as cthonic grandiosity (Phantoms of the Opera), nor the portentous religiosity that horror film aesthetic builds off, but a more modest inhabiting of environment, of space: what's not there, hidden in the corners, the barely there, that which will disappear again. (Houben's ever-present concern with the paradox a sound that exists in its disappearance, with the "presque rien" indications on Berlioz's scores.) For though, to say it again, the organ has reputation as grandiose, enormous cathedral spectacular, in fact Houben reveals it as a wheezing, mechanical instruments of stops and clicks and wheezes ("the organ is for me a Hoffmanesque instrument", as she says in an interview about the piece here), and at the same time a delicate, airy instrument of breath, of near-silence, sustaining a kind of cloud of sound that hangs in, through and as air, through pipes and stops and keys, at once intangible, evanescent, and weighted, heavy, with freighted tradition, with its un- and re-making...

On stage, Houben was flanked by the two members of the GBSR Duo, Siwan Rhys's piano gently prepared with horsehair, but more often played in a series of unadorned notes, melody reduced to its simplest means--one note, two notes, a few notes that almost, but don't quite, build up a scale or an octave transposition--or gently struck dissonances, reverberating in the sustain pedal and a finger-dampened string; George Barton's huge array of percussion played as a series of barely-audible taps, synchronised and overlapping piano and percussion entries over a single organ chord, sustained over the course of the entire work, not so much as a "drone" as a near-transparent texture, wheezing, breathing, enormous yet transparent, what Houben calls a "shelter" or a kind of sounding silence in which the players can each occupy their separate spaces, spread out on the stage; rather than Cage, for whom it's de rigueur to compare Wandelweiser music, I kept thinking of Nono, Houben's image of "the way" and his borrowing of Machado in the "no hay caminos..." motto that suffuses his late work, or the interplay of the piano and its outsides, its surrounding echoes and silences in "...sofferte onde serene", of the creation of sound as an environment, a way of remaking the space it's in.

Nono: "It is the inaudible, the unheard that does not fill the space but discovers the space, uncovers the space as if we too have become part of sound and we were sounding ourselves".Houben: "all together are rather more listening than playing.all together become aware of the different ways their sounds decay."

At one point the breathing of someone in the row above me was louder than the music coming from the stage, but there was almost no "actual" silence: a veil, a representation, a mediation. Somewhere in all of this a meditation on decay, on the anxieties of environment as not simply a "natural" space but a contested terrain of despoliation and the imminent ending of life--Houben's programme notes nodding to the anthropocene--or the histories closer to home, the current conflicts and conjunctures that seep into a place that doesn't, as the cliche goes, close itself off from them in a cocoon, but lets them enter and disappear. This is a historical music, a music maybe at the end of something, with the melancholy that implies, but also with the possibility of remaking and rethinking ("when the chord is unfolded, it sounds for a while, then the process of deconstruction begins"...)--spread out, as the performers were on stage, over large distance, chasms, yet with a kind of intimacy, a human scale, the possibilities of bodies in space, the possibilities of hearing as a mode of relation: a music that models eternity or infinity, as per Cage's ASLSP, its centuries-long sounding organ, yet which is in itself concerned with the material of decay, with a focused materialism. After an hour or so--just under or just over--the work ends, signalled with uncharacteristic drama or force by an inexorable, regular set of drum taps, one after the other, over and over: I didn't count exactly, but perhaps as many as fifteen times, a regular, barely reverberating stroke, flatly thudding, inexorably placed. A host of associations invoked: Beethoven's fate, Wagner's forge, yet the taps here also remove drama, ostentation, military forthrightness: and while those connotations can never render this a gesture "purely" formal or abstract, the context of the work as a whole, the manner of its delivery, lend this conclusion a non-forced materiality, at once transparent clarity and a refusal to be reductively read, rendered symbol.

Afterwards, Houben remarked that the piece, which exists in a different configuration each time it's performed, and is thus in essence never the same piece twice, might be considered as still sounding, still being performed. More to write and think about this...

Pat Thomas/Elaine Mitchener--Cafe Oto, 10th April 2022

(Image by David Laskowski)

This was the first time Mitchener and Thomas had performed as a duo, though they appear with Orphy Robinson and the visiting duo of William Parker and Hamid Drake on the expansive Some Good News album, also recorded live at Cafe Oto a few years ago, on which Mitchener is essentially the guest--and entirely at home--with two established duos, that of Robinson/Thomas and Parker/Drake. No prerequisites or expectations as to 'genre' here, this Sunday afternoon in early April; either musician could go anyway, together or separately. It's playing as listening, improvising, holding a line or--more often--knowing when to let it drop and hold back; Mitchener stepping to the side of the stage to listen to Thomas, solo, or vice versa. Both supplemented the complex 'basics' of piano and voice: Thomas with two i-pads functioning as kaoss-pads--an updated version of his earlier rougher, analogue electronics and tapes of the 90s, where he'd deploy tapes recorded off the TV, lo-fi musique concrete cut-ups and blarts of noise, but nonetheless treated with the same expert capacity for a kind of brusque disruption, a refusal to use electronics to coast or provide ambient texture; Mitchener with objects on a table, selectively deployed--a couple of whistles, a thumb piano, some rattles and shakers, used for specific and precise textures at particular points. No prerequisites, no expectations--and the opening five or ten minutes in particular all about finding ways into listening: Thomas scraping or stroking the piano's inside strings, Mitchener's quiet articulations, sometimes the amplifier buzz louder than the sounds they made; audience quiet and focused, this warm spring afternoon, so much lighter and more lifted than the lockdown of two years ago, a social space open to be whatever it might be, the openness of matinees like this, where the music can just be open and relaxed in its exploration, in its unforced listening.

Both Mitcher and Thomas have a penchant for intensity and volume: Thomas' electronic walls or, on piano, trademark thick chords, often clusters played with palms, the piano at once treated in its harmonic richness and rhythmically, as drum; Mitchener's virtuosity, her to turn any note into a series of gasps or rhythmic stutters, gargles, fluid yodels, effects for which the term "extended techniques" will have to substitute for a more precise technical designation--ululations reminiscent of transmuted marketplace or muezzin cry or folk music buzz, echoes of jazz--though almost never 'scat'--occasional avant-classical high pitches, pure and biting like laser beams, sirens, piercing through. But this was not a showcase of techniques, a kind of masterclass or workshop in displaying virtuosity; those impulses initially, and often throughout, kept muted, finding their way in, not forcing the music.

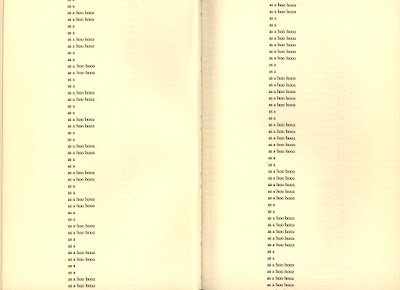

What was performed, with the interruption of a brief set break, was essentially one long piece divided into natural, unplanned episodes and pauses--though occasionally the audience broke in with applause to 'end' a section. Absent of a score, Mitchener used a series of texts--a Cecil Taylor poem on the elements and on creation("thrice water in air..."), Mingus and Jeanne Lee quotations on creativity, and, the most extended, poems by N.H. Pritchard, mainly from his second book, EECCHHOOEESS--which she moved through, improvising on or off, a word revealing itself gradually, cohesively broken down; the text not so much as a script but as a repository to give the voice shape, as texture and also as a space, a placeholder, a holding place for thought, for suggestion, for image. Pritchard in particular, who she's worked with before, formed the basis for the most extended (re)articulations of the set--the ecstatic yelling of the word "FR/OG" that closed the first set with aplomb, the poem of that name taken up again in the second half, Pritchard's splitting of words, so that "echoing" is reversed, mimesis of the aural effect rendered visually and then resounded--"ing echo", Thomas picking up on that echoic play with a rare melodic echo of Mitchener's pitched tones. An echo is one mode of relation, between the sounding and the sound, the semantic and the 'purely' sonic, the intentional and the unintended, the spoken and the spoken-for. Another--language's connecting words, the way they tie and fry, they fray: the spoken-sung recitation of Pritchard's mediation on and with the simile, "as a / as a / as a / hoo hooz", the call of an owl or the questioning of possession or colour gradation, "whose", "hue", words slipping and sliding, nature imitation, night birds or crickets, Thoreau's loon, nocturnes, clouds forming, faces in the sky, ("VISAGE / BLACK CLOUDBANK / FORMING/ ELSE WHERE") a kind of mystic-material inquiry rooted in (perhaps) American Transcendentalism, the reading of nature's hieroglyph as Emerson put it--letters, sounds, transparent eyeballs, bells--or theosophy, Toomer's Gurdjieff, his sound poems ("vor cosma saga [...] vor shalmer raga"), or a (post)structuralist enquiry into language--metaphysics or metaphor, any number of enquiries..."As a" as a repeated loop between speech and song, Thomas sometimes picking up with piano figurations that offered rhythmic support of staggered dance, more often with electronics on the i-pad that fed in insectoid cracklings or multi-layered clouds sustained then dying away.

I had a thought, but it was more a feeling, transmitted in the performance's vibrations, its sensations of tone, that this was all above all about material, about the piano as material, as object, as percussion, as an instrument with an inside and an outside, about how Thomas' performance "outside" on keyboard and "inside" on strings activated both, refusing distinctions between them; and how Mitchener too articulated inside and outside, clicks from the back of the throat while singing, the way the entire palette and throat is drawn into and made visible as articulation. It's about time, too, and poise, how listening gets articulated visually as well as sonically, in the way Thomas would hover over a chord, fingers in position, decide not to repeat it, move instead to the inside of the piano or the i-pad; the way both he and Mitchener insistently and unforcedly avoided the cliches of 'responsive' improv (echoing, playing 'together' in too obvious ways, as if that were the only way to play were to overcompensate by demonstrating you were 'listening' by imitation--which is not really listening at all, just a kind of language-learning game, a preliminary to the real listening that never really happens). Often Mitchener channeled an entire band in rhythm and lead parts herself, accompanying doubled vocal lines with a shaker, with a rhythmic articulation that supplemented and separated and merged from a melodic line (like an avant-garde Bobby McFerrin, occasionally); Thomas instead responding with a series of tranquil dissonant chords, or silence, or an electronic crackle, or in one delightful moment, a sudden burst of club music that faded in and out like the ghost of a different sociality, invoked with (im)perfect humour and (im)perfect ting, art brut, joyously knowing. Only at the end did he join or lead in a jazz-tinged series of chords that channelled a host of optimistically rueful medium-tempo solos exemplified by the solo Monk playing over the sound system when I entered the venue, and that maybe aurally echoed in his playing, that lent itself to song-like song-line close on Jeanne Lee's words on the experience of life as process, on life as living: not stasis, not object; and on those words, those chords, that song, synchronous, asynchronous, warmly to end.

(Pages from N.H. Pritchard's EECCHHOOEESS performed by Mitchener/Thomas)

No comments:

Post a Comment