A True Account collects works written between 2013 and 2020, published by a variety of small presses in the UK and the US. Here are variously refracted the student movement, austerity, general election, referendum, the crisis of 2020 or 2019 or any year you care to name; the Massacre of the Innocents, the housing question, the October Revolution in November; Sappho, Mingus, Storm Ophelia; Rukeyser, Rilke, Rodefer; the aesthetics of resistance, the insistence of history: luxury and voluptuousness, peace and pleasure, beauty and order, the questions that still remain unanswered and the problems that remain unsolved. “Wanting poetry to save my life, to shame my life, as LONG as the WORLD is WIDE, and as WIDE as the WORLD is LONG.”“Lyrically gorgeous and real poetry. This book is a bright spot in a bleak time.” - Peter Gizzi

Thursday 2 November 2023

A True Account

Monday 23 October 2023

"Moral Clarity"

Wednesday 6 September 2023

News of News of News of News

Sunday 2 July 2023

News of News of News

A short essay called ‘ “Key to a Savage Sideshow”: The Magazines of the Occult School of Boston’ up at Post-45 in a Little Magazines feature edited by Nick Sturm, focusing mainly on the one-shot Boston Newsletter assembled by Jack Spicer, Robin Blaser, John Wieners, Stephen Jonas and Joe Dunn one Boston summer. The issue also contains some fantastic pieces including Iris Cushing's piece on the first issue of Umbra magazine. Great to see Umbra scholarship continuing to develop and Iris’s piece will be very useful for those who haven't managed to see a copy of the magazine itself.

Also Umbra-related, my review of the Lorenzo Thomas Collected edited by Aldon Nielsen and Laura Vrana is out from Tripwire--online and it will also be out in the next print edition. I wrote this a few years ago--pre-Covid--so it’s nice for it to finally be out, with many thanks to David and Caleb.

A longer essay, ‘ “The Arc of Struggle”: Poetry and Defeat in the Work of Sean Bonney’, is out in‘No Future: Poetry of the Current British Crisis’, a special issue of Études anglaises edited by Dan Katz.

And the Multiple Melodicas set from Cafe Oto earlier last month is up at Douglas Benford's Soundcloud page: Douglas, myself, Georgina Brett and Steve Beresford all playing multiple melodicas, multiply. Recording thanks to Billy Steiger.

Monday 5 June 2023

Kaija Saariaho (1952-2023)

Barbican Centre, Sunday 7th May 2023

Anu Komsi, Anssi Karttunen, BCC SO/Sakari Oramo

For the final concert in a day of performances of Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho’s work, the BBC Symphony Orchestra came together to play four orchestra pieces spanning three decades, offering readings of rare radiance and clarity. From 1989, Du Cristal, the earliest work on the programme, is one long sustained, not-quite climax: an extraordinary array of textures shimmering and hovering on a brink of controlled delirium. With notes piled up on top of one another to create dense layers, the orchestral sound is massive, sometimes overwhelming, yet at the same time it feels as if something is being contained: a seething mass, a great, explosive force constantly on the edge. This effect of suspended movement is emphasized by five percussionists on an array of overlapping tuned metal—glockenspiel, crotales, triangles, tubular bells, xylophone, vibraphone—and multiple, booming kettle drums, with a synthesizer, harp and piano acting as a kind of additional rhythm section. Yet, particularly when witnessed live, what stands out if Saariaho’s care for individual detail: the fortissimo trill of a piccolo sounding out over the whole orchestra, a miniature choir wailing clarinets, the whole work ending, magically, on held harmonics from a single cello.

Written in 2020, Saarikoski Songs was the most recent work on the programme: it was here given its UK premiere by its commissioner, the extraordinary soprano Anu Komsi. The texts by Finnish poet Pentti Saarikoski—Communist, bohemian, translator of both Joyce’s and Homer’s Ulysses—offer nature poetry shadowed by pantheistic assurance and the threat of destruction. It’s hard not to read their words as dire warnings of the ecological catastrophe or the threats of war in the contested borders of and beyond Europe (as a Finnish war child, Saarikoski was evacuated to Sweden). “The forest is an academy obliterated by barbarians”, writes Saarikoski in the first text, ‘The Face of Nature’, reversing the cliché of “nature red in tooth and claw” by which human governments project social destruction onto nature, thus justifying their own actions. Across the world the Amazon rainforest burns: wordless melismatic syllables reach for high vibrating notes, twittering, rhapsodizing or lamenting, the orchestra aswirl on sustained tremolo or a doubled motif, a woodblock tap or rustle of bells, low, sliding strings, an unexpectedly lush string chord, as the soprano momentarily becomes “the song of birds lost in the extinction”. The subsequent settings are sardonic (‘Everyone from now on will have their own’), tenuously rhapsodic (‘All of This’), bitingly tensile (‘Bird and Sanke in Me’), and finally raptly mysterious (‘Through the Mist’), closing out on a final series of wordless held soprano notes and a final glockenspiel note which seems to condense the entire work into a single, miniature chime.

For me, it’s the closing piece Circle Map, that, along with Du Cristal, is the real highlight here. Written for the largest ensemble configuration of the night, this 2012 work sets poems by Rumi in their Persian originals. It is not, however, a conventional song cycle in the manner of the Saariskoski songs. Rather, recordings of the poems by Arshia Cont were electronically treated by Saariaho and her husband, composer Jean-Baptiste Barrière: broadcast on speakers surrounding the audience, they are both integrated into the orchestral texture and stand outside like a kind of radiant alien object (think the monolith in Kubrick’s 2001). Once more we hear swirling harp, tuned percussion, motifs that rise and fall into hushed held chords stretched like thin wires; plangent brass underscored by low piano rumbles, the orchestra as a swooning, swooping, shimmering entity full of rich inward song. The treated voice is a deus ex machina, not the meditative swooping soloist of the previous works but instead coming as if from the outside with the thrill of the integrated unknown, as the orchestra accompanies the echoing pitch cadences of speech translated to simultaneous monody. A film is projected over the stage, showing a hand tracing out script overlaid with superimpositions of computer-generated abstracted calligraphy along with the subtitled text. Close one’s eyes, however and far richer inner worlds emerge, attesting to music’s capacity to alway be more than the visual, more than speech. As one of the poems puts it, “whatever circles comes from the centre”. And that could be a principle for Saariaho’s music as a whole, its swirling still points, animated suspensions, its glittering clarity and mesmeric power.

Monday 22 May 2023

News of News

Some recent writing:

--On So Much for Life, the new Mark Hyatt Selected Poems edited by Sam Ladkin and Luke Roberts, for The Poetry Foundation.

--On Elaine Mitchener's forthcoming performance of Peter Maxwell-Davies's Eight Songs for a Mad King for The Wire here. A longer piece on Eight Songs and its contexts is brewing somewhere along the line.

And some upcoming gigs:

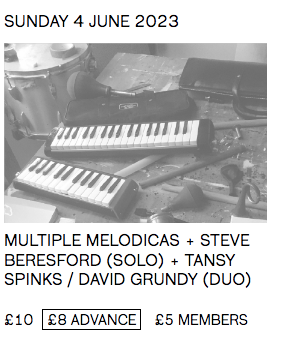

--Following a gig at waterintobeer last month, a second outing for Multiple Melodicas (me, Douglas Benford, Steve Beresford, Georgina Brett, Martin Hackett) at Cafe Oto on the afternoon of Sunday 4th June, along with a solo piano set by Steve Beresford and a duo set by me on piano and Tansy Spinks on violin. Details here.

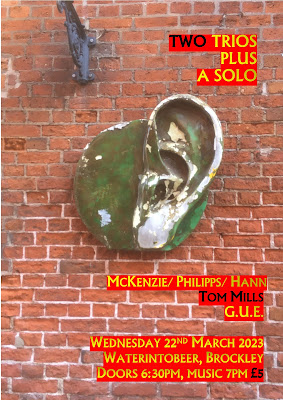

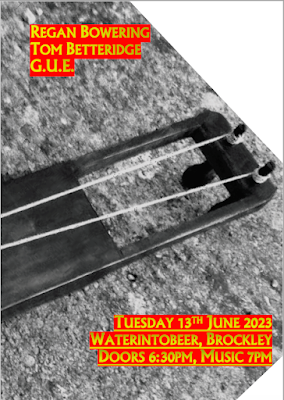

--Also planning another gig by G.U.E. (me, Jacken Elswyth, Laurel Uziell) on a bill with Tom Betteridge making what I believe is a live solo debut and Regan Bowering on electronics/objects/snare drum. This one will be at waterintobeer in Brockley on Tuesday 13th June, doors at 18:30. Tickets here.

We've been going through hours' worth of GUE recordings made over the past year or so so a release of some sort will be on the cards at some point soon.

And in other news...

--Following the launch reading with James Goodwin and Candace Hill last month, Howard Slater's review of Candace's Short Leash Kept On at Northern Review of Books here. (The book is available at the Materials website.)

--And there's also a nice review from Tom Allen of Present Continuous at LA Review of Books.

Finally, Materials will be relocating to Berlin in July, joining Materialien in Germany, which may involve some logistical shuffling and slower processing for orders. But expect more news the other side of the move...

Friday 19 May 2023

"The Subject of Emancipation": Trilce Translation Launch

|

punctuates time with its physical order; it creates a time that’s equally subdivided and empty. Language administers it.Whether one is in actual prison or not, prison-time is a static present, an empty time excised from the continuity of time’s movement. But the time it takes to say the word time continues. The juxtaposition of these two times, sun-glare of nausea, is beat out by the poem’s metronomic repetition of words in twos and fours. Vallejo was imprisoned on remand for 112 days.

Thursday 27 April 2023

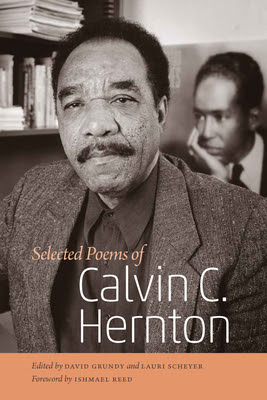

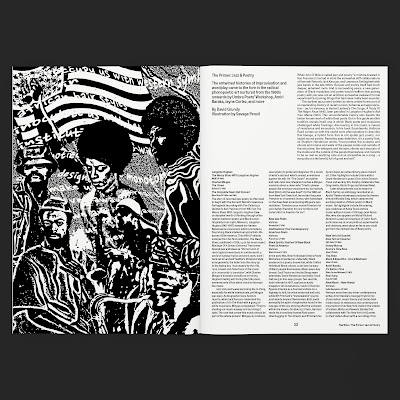

Selected Poems of Calvin C. Hernton: Preview

Thursday 20 April 2023

Latest

Sunday 2 April 2023

In other news...

On Thursday April 13th I'll be playing with a new group, Multiple Melodicas, at waterintobeer in Brockley, South London: myself, Georgina Brett, Steve Beresford, Douglas Benford, and Martin Hackett on melodicas, along with solos sets from Eddie Prévost and N.O. Moore. Unit 2, mantle court, 209-211 mantle road, brockley, se4 2ew. Doors: 6:30pm for a 7pm start. More details and advance tickets at the eventbrite page.

But, as well as music, this work is also conversation--talking (talking to, talking about, talking with, talking back). "I want to talk about the tears and sorrows of the people", he says in his introduction. And this concept of "the people" is a global one, Thomas reading his poem in memory of Neruda and translations of work by African poets--that internationalist, multi-lingual aspect running through his work: poems by Francisco José Tenreiro, Agostinho Neto, Marcelino Dos Santos, the latter then emerging from the victorious struggles against Portugal in Angola and Mozambique. Thomas' work of the 1970s, as he honed the finely-poised ironies of his earlier work through the lens of his experience in Vietnam and his reading in writers like Christopher Caudwell, is a contribution to a left populist poetry that has been virtually ignored: far too few notices of the Collected Poems edited by Aldon Nielsen and Laura Vrana have made it into print. (I've so far been unable to place my own review.) But being able to watch this video, to hear Thomas' cadences, his sonorous rise and fall, helps to newly bring that work alive: a poetry that charges the space, crackles with fierce energy and moral compulsion.

Thomas read with David Henderson, fronting the nine-piece band Ghetto Violence--as singer...(in this harking back to his early career with vocal group the Star Steppers, as documented in Henderson's classic early poem 'Boston Road Blues' (for the poem, scroll down to page 41 here.) In the U.S. Bicentennial Spring, Henderson and the band deliver "Hail to the Chief" ("agit-rock...dedicated to the next Presidential election". In the event, Jimmy Carter would replace Gerald Ford, who'd pardoned Richard Nixon for his Watergate crimes, in the recurring cycle of putatively 'democratic' debasement. It continues.

(The full recording of Thomas' and Henderson's reading is here.)

Also from the Poetry Centre's Digital Archives, another gem: Karen Brodine and Meridel LeSueur reading in 1981, two generations of Left feminist writing looking into the jaws of the 1980s with implacable courage. What's particularly valuable is to have this document of Brodine reading the entirety of the sequence Woman Sitting at the Machine, Thinking, written from her experience of workplace organising as a typesetter (and her reading of Engels). I'm working on a chapter on Brodine, Merle Woo and Nellie Wong for a forthcoming book on queer poetry in Boston and San Francisco which hopefully will be fully drafted in the next few months. Last year, I spent a valuable week in Brodine's archives at the James C. Hormel Center on the top floor of the San Francisco Public Library, Tim Wilson and the other librarians patiently bringing me box after box and allowing me to see, in her unpublished notebooks, drafts, teaching preparations, and talks, how, for her, poetry articulated her sense of herself as woman, as lesbian, as worker, as socialist, the clarity of the way she theorizes language, the specific uses she sees poetry as fulfilling: conceptions well beyond the cliche of poetry as a kind of transparent vehicle for messages, on the one hand, or as 'neutral' abstraction on the other. For Brodine, poetry's form is its argument: which is to say that "form" is inseparable from, dialectically related to "content", the distinction between which she skewers in her unpublished pieces on aesthetics. We all know the rhythms of our days, shaped by labour or its absence, in our different ways, some feeling the pinch more than others, and spending time with 'Woman Sitting' in particular, going over it and again, still enables a reckoning with and refiguration with the violence of that time, the violence of Brodine's and our times: this poem which is so much about time, about the work week and the ways workers work within and resist capitalist time.

knowledge this power owned, nor shared

owned and hoarded

to white men [...]

wrench it backknowledge is something we have

Here's Brodine's reading:

And from the same reading it would be negligent not to mention Meridel Le Sueur's poems of fierce solidarity, reading the global and gendered division of labour in ways that, once again, are firmly internationalist, are about mapping the general and the particular in precise and specific ways that poetry--specifically--can be used as a tool to pry open, a compass for navigation. And Le Sueur's opening denunciation of Eliot's The Waste Land as nihilistic male modernism remains as hilarious and as provocative as it's meant to be...

Friday 10 March 2023

Gaia: Two Orchestral Works by Wayne Shorter

Two luminous orchestral works by the late, great Wayne Shorter: first, Dramatis Personae, a Lincoln Centre Commission from 1998 with Shorter on soprano, Jim Beard on piano, Christian McBride, bass, and Herlin Riley drums alongside orchestra conducted and arranged by Robert Sadin--the bridge between the monumental, and underrated, High Life (1995) and the orchestral collaborations of the Danilo Pérez/ John Patitucci/ Brian Blade acoustic quartet to come.

A decade-and-a-half on, the massive LA Philharmonic commission Gaia (2013), described by Richard S. Ginell in Variety as a “murky, thick-set monster of a piece [...] massive, slow-moving, opaque textures, sometimes tracking Wayne’s distinctive long, snaking melodic lines on soprano; treating the sections of the orchestra as blocs”. Varying in performance from 25 to 30 minutes, this version from Gdansk in 2014 veers toward the latter, with Shorter on soprano forming part of a quartet with Leo Genovese (piano) and Terri Lynn Carrington (drums); the solo vocal part and libretto are by Esperanza Spalding, who also doubles on bass as part of the quartet.

Shorter first began work as a teenage student at NYU, and it’s to be hoped that Shorter’s Kennedy Center collaboration with Spalding on the opera Iphigenia--his final piece after he retired from performing in 2019--might appear in the future. For now, the serene drama of these orchestral works represent the majestic, achieved late blossoming of the compositional impulse Shorter had been building throughout his entire life, from his early work on that teenage opera through to the unreleased orchestral pieces Universe, Legend and Twin Dragon he wrote for Miles Davis in the 1960s and ’80s (later realised by Wallace Roney) and the misunderstood trilogy of post-Weather Report Afro-futurist epics Atlantis (1985), Phantom Navigator (1986), and Joy Ryder (1989), along with the aforementioned High Life.

I have a longer piece on Shorter in The Wire, with thanks to Meg Woof.

(Edited down from a 30,000 word draft--with plenty more to say on Shorter’s orchestral work, his status as composer, and the framing of ‘jazz’; more of that may see the light of day elsewhere.)

///

In other news:

My interview with composer Hannah Kendall is online at Bachtrack: Kendall is Composer-in-Residence at the Royal Academy of Music this March, and a couple of concerts are forthcoming the following week. Highly recommended if you’ve not heard her music in performance before.

Saturday 25 February 2023

News and Views

In February I was interviewed about A Black Arts Poetry Machine by João Paulo Guimarães (University of Porto) and Elina Siltanen (University of Turku) for the online Poets Talk Politics Series hosted by the University of Porto. Thanks to João and Elina for the questions and discussion, and to João for the invitation. The event was live-streamed and should be uploaded to the Youtube channel of the Instituto de Literatura Comparada Margarida Losa in the next few weeks. For now, it's available on Facebook, as embedded below (no need for an account) or at this link.

Also online is the video of the online launch for Present Continuous back in January, hosted by Malvika Jolly and with responses from Tyrone Williams, Linda Kemp, Ciarán Finlayson, and Ghazal Mosadeq, can be seen on the Pamenar Press Youtube channel here, or in the video embedded below. Many thanks to Malvika for hosting and Ghazal and Hamed for publishing, designing and typesetting the book!

Some photos from the 'Electro-Acoustic Responsiveness' gig at IKLECTIK with Eddie Prévost (percussion), John Butcher (tenor and soprano saxophones), N.O. Moore (guitar), Emmanuelle Waeckerlé (voice, objects), and Tony Hardie-Bick (electronics), courtesy of film-maker Stewart Morgan, whose film on Prévost should soon be nearing completion.

And some photos from the Materials/Materialien reading at Halle für Kunst Lüneburg, with James Goodwin (launching the new collection Faux Ice), Lütfiye Güzel and Laurel Uziell: thanks to curators Ann-Kathrin Eickohf and Elisa R. Linn.

James will be doing a UK launch for his book at Café Oto in Dalston on Sunday 9th April; this will also be the launch for Candace Hill's astonishing book-length poem Short Leash Kept On. James will be in conversation with Nisha Ramayya and I'll be in conversation with Candace via Zoom. (Fred Moten will be reading, in his trio with Brandon Lopez and Gerald Cleaver, later in the evening.) Tickets from the Café Oto website.

Finally, in further Materials news, Anne Boyer's Money City Sick as Fuck and Lisa Jeschke's The Athology of Poems by Drunk Women are back in print and can be purchased from the Materials website at the following links: Boyer here and Jeschke here.

%20Wire%20471%20Jason%20Moran.jpeg)