[MaerzMusik happened in March this year. This is an extended cut of a much shorter review out in The Wire, split into three parts for ease of reading. Part 2 is here, Part 3 is here.]

Part 1: Nguyễn + Transitory, Susie Ibarra, Pamela Z, Joan La Babara

I caught half-a-dozen performances at this year’s MaerzMusik, held across a variety of venues in the city. Since its rebranding as MaerzMusik in 2002 (it was originally funded as the International Festival of Contemporary music in 1967 as a Biennale), the festival has gone beyond the usual remit of Neue Musik to incorporate a wider generic framework, and, under Kamila Metwaly’s curatorship, it feels like an open and generative space aesthetically.

Offering a particular context, MaerzMusik exists within a context. Berlin’s—and Germany’s—state-funded art scene has been in some turmoil of late, increasingly doubling down on the censorship of Palestinian and pro-Palestinian voices during a continuing western-backed genocide and facing funding cuts from a conservative city authority, sure to be doubled down on with the newly elected, right-leaning coalition government in the years to come. At a recent performance I attended (not part of MaerzMusik), after the choreographer spoke out about state censorship and the deportation of friends for pro-Palestinian sentiment, the director of the venue hastily stepped in to distance themselves from the remarks, to boos from the audience. Similar rebuttals around Nan Goldin’s intervention during her Neue Nationale Galerie show have drawn fresh attention to the institutional censorship that has brokered the Strike Germany campaign. In the past month, a particular university prevented a UN representative from speaking after pressure from the city mayor. Criminal cases are ongoing against protesters. And so on. The pro-Palestinian sentiment of artists or audiences and the anti-Palestinian sentiment of institutional funding bodies speaks to the contradictions of the German state position, one which reflects the turns towards general condemnation of Israeli actions against civilians on the part of the German population, a topic on which virtually none of the main political parties are willing to speak out. The state that supplies the weapons and the denials also supplies the art. Given this, these days, in any state-funded event in Germany, despite the rich diversity of art on offer, sometimes what’s not heard is as telling as what is. This is not so much an expression of a crisis we’re heading towards as a crisis we’re already in: the rise of the far right, of authoritarianism in general, of a turn, in Europe, towards an enhanced war economy, with a blind eye to genocide and dictatorship. This all risks becoming a litany that denudes itself of meaning in its rote familiarity. But it bears repeating.

So to the music. At the riverside Radialsystem, the duo of Nguyễn + Transitory present Drifting to the Rhythms at the Southeast of Nowhere, which, in a post-concert talk, they call a “symphony of intimacies”. The latest configuration of the duo’s ongoing collaborative project, the piece refigures exactly how an audience might think of the relation of music and dance. It is at once an instrument and a score, which is both ‘played’ and composed in real time by the performers, as the dancers move over copper lines on the stage floor and interact with a rope interlaced with copper wires above, triggering electronic sounds in ways that change depending on their movements. This particular iteration opens with the five female dancers, all from Thailand, gathering around a glowing light as if round a fire, followed by collective procession in silence, each dancer sharing the same gestures: a moment of collective regimentation which gives way to a series of highly virtuosic solos, duos and trios. In their essay in the programme, Bussaraporn Thongchai contrasts the fluidity of Thai folk dance with the Thai court dance, focused in Bangkok, a ‘prestige culture’ with fixed conventions, and the dancers thus perform folk dances from more neglected regions of Thailand, especially the North-East.

With some using traditional movements and some merging them into a more contemporary vocabulary, the performance includes dances interacting with spirits and movements from a martial art traditionally performed by men. As the artists discuss in a post-show talk, the all-female piece follows a loose scenario of queer desire—meeting, coming together, strife, negotiation with society, acceptance, and the return to the collective—but it would be a mistake to call it obviously narrative. The four-sided stage is devoid of scenery or backdrop, and while engaging the traditional background in dialogue, the movements themselves are also abstracted from their original context. Tradition—at least in the folk dance that Thongchai describes, a tradition from below rather than from above—is not something fixed, but something which is improvised upon and with, and the dance—particularly for those in the audience, like myself, unfamiliar with this context—creates scenarios that morph and change fluidly without being necessarily illustrative. Throughout all of this, the electronics emit a booming bass drone which forms a kind of ever-present base on which both sound and movement build: moments of erotic intimacy, bursts of energy triggered by samples of traditional music in brief loops, and, in a particularly striking sequence, a kind of battle with copper poles.

The feet are the proletarian of the body, said Etienne Decroux. “Take a walk at night. Walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears”, writes Pauline Oliveros in the fifth sonic meditation, ‘Native’. The foot is where the body encounters the earth. And in this performance the feet are where the sound is triggered. As the show’s title gets us to think: what is the supposed centre we are Southeast from? The foot turns on the axes, shifts them. This sound, this drifting rhythm.

The modern Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche stands next to the preserved ruin of the original, bombed church in the midst of a busy shopping square. Slightly sunk into the ground, its stained-glass windows blocking out the surrounding buildings with a light that seems to exist somewhere between day and night, it’s an appropriate setting for a concert-length work by Susie Ibarra, CHAN: Sonnet and Devotions. Largely through-composed, with the exception of improvised accompaniments to the poetic recitations, the piece integrates poets Logan February and Don Mee Choi with a full band including singers (soprano and tenor), harp, bass clarinet, trombone, French horn, acoustic and electric guitar, viola, double bass, the venue’s pipe organ, and Ibarra herself on drumset, gongs, and percussion. Titled for Ibarra’s middle name, which means ‘meditation’, each piece is a kundiman, a type of Filipino love song, with the love in this case devoted to ecosytems rather than individual humans: German forests, Himalayan lakes, the Pasig river in the Manila bay which, declared biologically dead in the ‘90s following industrial pollution, has recently come to life again.

CHAN opens with birdsong, the ensemble joining in the mood largely maintained throughout, of an occasionally restive calm. Over its multiple movements, it changes paces like the gentle fluctuations of breath. Ibarra rarely features the full ensemble, but instead uses it as a set of juxtaposed and overlapping timbral fields: a wheezing organ accompanied by the gentle pluck of harp and acoustic guitar, a soprano and viola duet; a particularly beautiful moment for Hilary Jeffrey’s muted trombone over electronics and Ibarra’s percussive rumbles. The musicians sit in a semi-circle round Ibarra, who plays and conducts from the drumkit. Though her playing is not the principal focus, at one point she offers a beautiful solo, characterised by carefully crafted melodic momentum; at another she rattles hand bells, uses brushes to play the air itself as if harnessing the rhythm of the wind. Most visually striking is the speaker tree sculpture standing to the side of the ensemble: ten speakers branching off a central wooden pole, which over the course of the concert play field recordings, percussion, and at times seem to offer real-time manipulation of sounds. At different points, the poets pick up separate, portable speakers and carry them down the aisles, while soprano Otay:onii (Lane Shi) scatters invisible flowers to audience members from an empty bag. In the final movement, Logan February recites from the organ loft, a poem playing on the classic trope of. the interaction, or distance between, the bodies of human lovers and the metaphorical transfer to a surrounding environment: “you must remain”, they intone, before a final ensemble melody closes the piece quietly. A distinct and beautifully integrated work.

We’re now at the mid-week point, and solo recitals by Pamela Z—a recital called ‘Other Rooms’—and Joan La Barbara—titled after her debut solo album ‘Voice is the Original Instrument’—take place down the road at the blackbox space next to the Festspiele Haus. Alone onstage in black box setting with two laptops, one for voice and one for video, and two gesture-activated MIDI controllers, which trigger live samples like a theremin, Z transforms herself into both soloist and accompanist, a one-person choir, deploying tuning forks struck to ring against the microphone, the snap of popped bubble wrap, and the soaring echo and delay of her voice, in words spoken or soaring into song: counting to twenty in multiple languages, fragments of French, descriptions of spent flares on a pavement “like broken swastikas”, while video projections accompany the pieces, similarly interested in looping and transformation.

Z is interested in the way an object, a concept, a theme, blurs the edges of perception, using the MIDI-controller to “play” the keys of a typewriter in the air as he mimes composing a letter, or using an avian sample to turn herself into a whistling, chirping bird, pitch-shifting, shape-shifting, transforming. There’s something of the stage magician about the intricacy of the display: at once showing how it’s done and leaving one to marvel at the many shapes into which Z twists her body and voice. Fragments of language and gesture are gently tweaked, pulled apart and reconfigured into songs at once tightly woven and with a sense of the glittering slipperiness of an ordinary language that, on the brink of articulation, runs away from us, our assumptions—not least, the idea that there is a singular, un-inflected ‘we’ or ‘us’—and into that space we call music.

Like Pamela Z, La Barbara also works heavily with the microphone—which, in a post-concert talk with soprano Nina Guo, she describe as “part of her instrument”. Her pieces tend to last for longer, offering morphing soundscapes—“sonic atmospheres” or a “pool of sound”—in which the higher chirps of her younger self on tape—what she calls her “backing tracks”—interact with the deeper register of her current voice: a combination of “sounds that I know and sounds that I imagine”. The scores, she explains, are often “vocal gestures” that are notated graphically: La Barbara experiences sound as shape, and in many cases is working with sounds for which there is no conventional notation—sounds whose operations, at least initially, are as mysterious to hear as to her auditors.

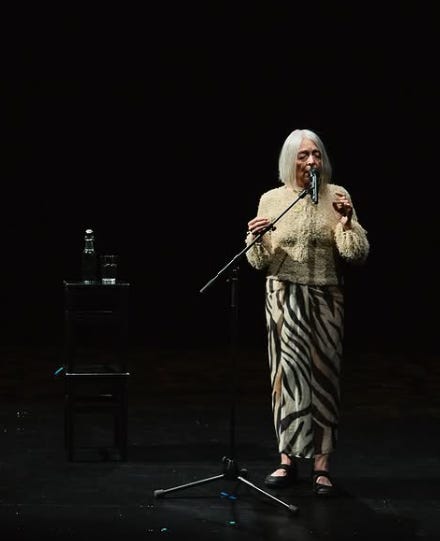

La Barbara stands onstage in a single spotlight, larger pools of coloured light gradually emerging behind her, roughly equivalent with the layers on the work’s tape parts. The first piece, ‘Erin’, comes from 1980, and was inspired by the photograph of the father carrying the coffin of his son who’d died in the hunger strike at Long Kesh. It begins with energetic high pitches, babble and chatter, simulating conversation, perhaps, a collective sharing of stories, swirling round the speakers, before turning into a kind of lament for pitch-shifted low voices, ending on a final burst of the chatter as if to single hope remaining. ‘Solitary Journeys of the Mind’, one of the more recent pieces, serves as a framework for La Barbara’s improvisations, moving round the harmonics of a single note then up to the level of throat-singing or yodel. Technically impressive, the work’s effect is not of virtuosic display, but more of a kind of singing to the self, following a line in meditative exploration, rumination as much as ecstasy. The lament, or at least a quality of reflection, that characterizes ‘Erin’ to some extent goes through all these works. ‘October Music’ offers a portrait of the California night sky realized at IRCAM. Like Pamela Z, though without the MIDI controllers, La Barbara moves her hands to shape the sound: conducting, as a body conducts or carries sounds or force. Only in the final piece, the ‘opera in progress’ ‘Windows’ do we hear any other sound than those derived from La Barbara’s live and recorded voice. Samples from a decades’ worth of instrumental recordings, swirl and build on the edge of climax, in a febrile, moving structure. To the sounds of a ringing bell and gently lapping water, La Barbara sings with a kind of shrugging motion, the music slowly subsiding, now at rest.

Four concerts in, there were still many hours of music to come...

To follow: Part 2—Mazen Kerbaj’s Lungless.

No comments:

Post a Comment