[Extended cut of two pieces for The Wire: a longer online piece (available here) and a shorter piece for the print edition (issue 491/492).]

Always, already there: an incubator for Afrodiasporic New Music

Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 4-10.11.2024

Over the course of seven days at Berlin’s HKW (Haus der Kulturen der Welt), a programme of concerts, panels, and lectures focusing on Afrodiasporic composition offered one of the richest, broadest spreads of Black New Music I can recall encountering. Described as an “incubator”, the event reflected the tireless and polymathic activities of George E. Lewis, who in recent years has gone from being one of the famed voices in the AACM as an instrumentalist to a music historian and theorist, professor at Columbia University, New Music composer and probably the leading figure worldwide for the Black presence in New Music. There was enough going on here for at least two years’ worth of festivals. Somewhere between a symposium, a conference, a concert series, a festival, with internal discussions amongst the numerous musicians and composers built in as part of the programme.

Several participants suggested this was maybe the first of its kind—at least, in Europe, and at least, in the past half century or so—and far more took place than can be properly summarised here. (A beautifully-designed booklet was produced for the occasion, and can be downloaded from the event page.) The public-facing element involved daily roundtables in the Safi Faye Hall, joined at the weekend by four concerts given by the International Contemporary Ensemble, which Lewis currently directs, featuring music by no less than twenty different composers, one devoted to the music of Douglas Ewart, and a closing concert also featuring members of Berlin-based biopic Com Chor.

At one point in the discussions, Lewis referred to the “maelstrom of knowledge” being unleashed, and during the week of events, names, facts, dates, ideas popped out at a prodigious rate. I was scrambling to take notes for this piece, but even if I hadn’t been, I would have had to write things down. There’s only so much one head can retain. In itself, this is conclusive evidence of the incubator’s principal contention: that Afro-diasporic composers were, are, and will be present in classical and New Music contexts for centuries, even when those contexts were and continue to be systematically racist and in which those who do manage to make it into those worlds are often written out of the history books. (Take a look, for example, at the 363 different artists listed in the MBC Living Composers Directory.)

The incubator took its name from the late James Snead’s classic essay on repetition in Black culture. In this wide-ranging essay, Snead turns Hegel’s infamous characterisation of Africa as a-historical and static against itself: being “immediate”, the African “is always there in any given moment”, writes Snead. “Being there, the African is also always already there, or perhaps always there before, whereas the European is headed there or, better, not yet there.”

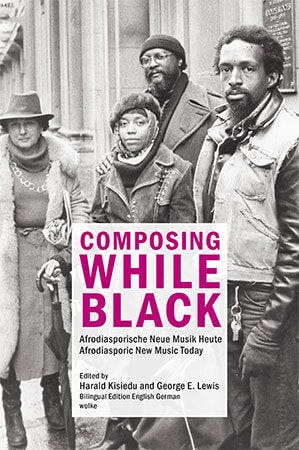

Reversing the familiar dictum of ‘progress’ and ‘development’, then, we might say Europe has still not caught up or got to where it’s heading, and during one of the talks, Nigerian composer-musicologist Akin Euba was quoted, to the effect that the great even of the twenty-first century will be to de-centre Europe. That work is already happening. Most immediately, Always, already there builds on the bilingual English/German book composing while black: Afro-diasporic new music today/ afrodisaporische neue musik heute, edited by Harald Kisiedu and George Lewis and published by Wolke Verlag last year, reviewed by Peter Margasak in The Wire’s August 2023 issue, and those interested could do worse than starting there. It also builds on events organized over the past few years, largely within the new music scene in Germany—still one of the best-funded and prominent in Euro-America—such as Berlin’s Maerz Musik. In 2020 this saw Elaine Mitchener instigate the first invitations of Afro-diasporic composers to the classical section of Donaueschingener Musiktage , and in 2023, Lewis, Braxton and Tyshawn Sorey were featured artists at the Darmstadt Summer Course.

Darmstadt and Donaueschingen have long been regarded as bastions of European new music. Numerous Black artists had appeared over the years at the latter’s now-defunct jazz strand but, until Mitchener’s commission, none at the principal, new music section, itself telling of the status of the likes of artists like Sun Ra, Archie Shepp, Anthony Braxton, and Lewis himself. Such was a case, as Lewis remarked in his opening address, of ‘mis-genreing’: an assumption that Black artists could not be composers, that composition and improvisation were somehow unrelated. It is impossible not to see this as racialized—that’s to say, as structurally racist. As Harald Kisiedu notes, 1967 saw the recording of two key documents of 1960s free jazz: Shepp’s Life at the Donaueschingen Festival and the second performance by the Globe Unity Orchestra (later released on Globe Unity 67 and 70). But, as Harald Kisiedu notes, while Brötzmann was labelled as ‘Komponist’—composer—receiving the according fee, Shepp was labelled merely as ‘Interpretet’, interpreter, despite the fact that, of the two, Shepp was clearly the more focused on compositional methods.

But the point is not to focus on historical wrongs. What’s key here is the equal focus on living artists and on the work of historical retrieval or legacy, beyond the focus on single figures as representatives of entire swathes—say, Julius Eastman for new/experimental music and Florence Price for more traditional classical forms. As Lewis remarked, one of the seeds for the events was laid when he attended a concert of Eastman’s work at Maerz Musik, and noticed the audience’s appreciation, wondered if Eastman was the only Black composer they’d ever heard, or heard of.

Precarity has long been a condition of Afro-diasporic new music, Lewis noted. Lewis knew Eastman during his time as director of New York avant-garde venue The Kitchen; in 1983, getting back to New York from a tour of Japan with Gil Evans, he met Eastman on the street, who told him that he was now homeless and had lost all his scores. Julia Perry—whose work was subject of a recent release by the Experiential Orchestra and a festival in New York this March—was awarded two Guggenheims and studied with Luigi Dallapiccola, but ill-health and the lack of a publishing deal meant that essentially nothing more was heard until a very recent revival.

Yet the point, as Lewis argued in an introductory talk on the Monday, is not to lament the absence of Black composers and artists from various historical art movements as if they never existed, but rather, to argue that they were always hiding in plain sight: in Lewis’s words, to “smash the myth of absence”. The term ‘Afro-diasporic’ is carefully chosen: rather than treat Blackness as a near-exclusively US phenomena (what Lewis called an “undeserved hegemony”), the composers here encompass Africa and all its diasporic traces, including those within Europe. Composers featured here have ancestry, live and work in Canada, DR Congo, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guadeloupe, Guyana, Jamaica, Kenya, New Zealand, Nigeria, Martinique, South Africa, Switzerland, the UK and the US.

From the invention of jazz on instruments discarded by European marching bands to the rhythmic innovations when drums were taken away from enslaved persons and the creative repurposing of turntables and samplers, Black music has always improvised on the given, syncretic and ‘impure’ at root. It’s white critics who historically have tried to draw boundaries and borders, to police genre, to set imaginary boundaries and then to criticize Black composers for crossing those lines. To disallow entry in white orchestras and conservatories for the likes of Mingus or Simone is part of the same discriminatory world view as those critics who denounced composers like Anthony Braxton for overstepping the boundaries of ‘jazz’.

Expansiveness is the watchword. As Lewis emphasized, one of the purposes of such events is precisely to de-provincialize the Euro- and US-centric focus that dogs so much of our understanding of music, perhaps most especially of all in classical and new music, so that Europe, and what has been called the ‘western’ tradition, emerges as just amongst many localities that make up music’s possibility. European classical music itself was a form of identity politics: a “form of sensory deprivation’ leading to an “impoverishment of the field”. Lewis’s aim is instead to “form a new creolized and maroon identity for classical music writ large”, one that recognizes it as already creolized, a “diasporan music that’s performed all over the world”.

Lewis here draws on a term he’s returned to repeatedly in the past few years, taken from Jean Bernabé, Patrick Chamoiseau and Rafaël Confiant’s 1990s manifesto Éloge de la Creolité, or In Praise of Creoleness, which takes the tri-continental mixture of cultures fostered by colonialism in the Caribbean as model for a new conception of global, ‘mosaic’ identity, along with the metaphor of slaves running away to form multi-cultural ‘maroon’ communities in the hills and forests, away from the forced labour of plantations. (“Marronerons nous Depestre?” (“shall we marroon ourselves Depsetre?”), writes Aimé Césaire in a famous poem to fellow poet René Depestre in reference to the socialist realistic dictates of the Communist Party; the metaphor of marronage as political model has been picked up in Neil Roberts’ recent book Freedom as Marronage.)

As documented in poet Kamau Brathwaite’s classic study, in the Caribbean, Creolization was initially a violent process of enforced ‘acculturation’—by which two cultures blend, but with the subordinate culture in general subordinated to that of the majority, involving processes of what we’d call today ‘cultural erasure’. Yet it also functioned as hybridization, or ‘interculturation’, by which the dominant culture is subverted and changed from within. The syncretic practices of vodou and santería, the disguise of subversive messages through music, the way that forms of Afro-American music with African roots became the sound of global popular music—all these suggest that the process works both ways.

As Lewis notes, the model of ‘diversity’ by which historical erasure of the Black presence within culture has recently been redressed still assumes the model of a dominant culture as centre, adding bits and pieces here and there but ultimately remaining unshaken from its central role. Lewis himself prefers the term ‘new complexity’, cheekily borrowed from the journalistic term used in the ’80s to describe the dense and hyper-virtuosic music of composers like Michael Finnissy and Brian Ferneyhough, often seen as a reaction to the ‘new simplicity’ and the return to tradition—tonal harmony, Romanticism, melodicism—on the part of Euro-American composers. A new, creolized view of new music would be “the newest new complexity”, part of a process of “complexifying identity”. Such “interculturality”, Lewis suggested, could offer “new visions of what cultures of the world could be like”; or, as HKW director Bonaventure Soh Bjeng Ndikung interjected, “nothing else but the norm”.

Historically, it’s been assumed that Black musicians tend to play popular music; or, if they don’t, and lean more towards the experimental or composed, that they play ‘jazz’ (once jazz is rechristened an art music). The point is to demean or degrade that term, establishing a hierarchy of ‘new music good, jazz bad’: rather, as Ndikung noted, it’s “both to fill up existing categories, and to create new ones” that “bridge” those already in existence. “There is no music from around the world that is not experimental, and none that is not classical”, he remarked. Against both a progressivist model inherently suspicious of tradition—while assuming that ‘tradition’ means that of ‘western’ music (in reality a relatively recent and local phenomenon within Northern Europe in the last couple of centuries)—and a traditionalist model devoted to doggedly defending precisely this parochial conception against attacks from all manner of perceived outsiders, this would move closer to what Cedric Robinson terms the ‘Black Radical Tradition’ and Amiri Baraka ‘the changing same’—a holistic sense in which tradition can be resistance to the norm, to forced acculturation, and in which built into it is the very idea of change, of improvisation, of resistance to enforced fixity.

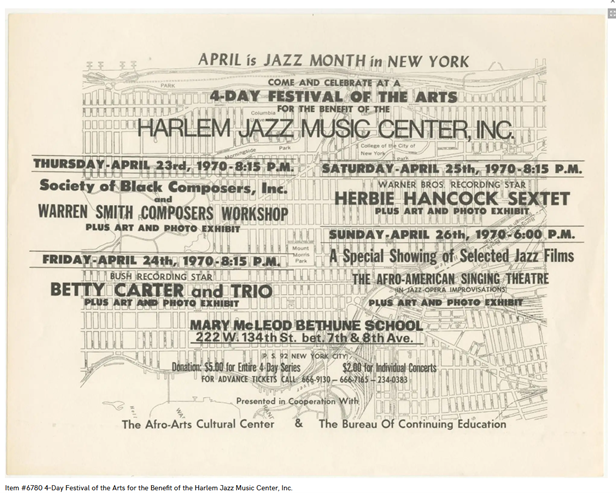

If the first day’s talk was expansive and wide-ranging—beginning with Cameroonian musicologist, writer and musician Francis Bebey and ending with the future of the world itself—Harald Kisiedu’s lecture on the Society of Black Composers the following day offered some patient historical context. Formed in 1968 by composers Carman Moore and Dorothy Rudd Moore, among others, with Fluxus artist Ben Patterson as president, the Society lasted five years, organizing concerts and discussions and connecting composers across the US. (A photo of Society Composers Julius Eastman, Tania León and Talib Rasul Hakim appears on the cover to Composing While Black.)

In the months before the Society was founded, Kisiedu noted, students protesting segregation had just been massacred in Orangeburg, and Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy had been assassinated. Kisideu’s talk made persuasive contextualisation around the broader context of the Black Arts Movement and groups, generally associated with jazz—though, as Kisiedu noted, equally concerned with composition—such as the AACM and the Black Artists Group. Self-organisation was here a political imperative, and if the sphere of classical music has given the Society less of a militant reputation than the purveyors of free jazz or the New Black Poetry—if that, is, it’s talked about at all—politics was no less central.

As Kisiedu notes, the SBC recruited musicians more generally thought of as jazz than classical musicians, but who might be considered composers, among them Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp, and Herbie Hancock. Drawing genre boundaries was not part of their operation. During this time, fierce debates spiralled about the meaning of ‘Black music’? Did it imply the use of certain, ‘authentically African’ sound materials, and the absence of other, ‘white’ or European materials? One trend, for instance, saw electronic music as an ‘unnatural’ western imposition, while another—notably in the work of Sun Ra—used electronics to afford Afro-futurist visions of both past and future. The Society itself cleared up the matter in its 1969 newsletter, arguing that “a common vocabulary or grammar is not even desirable among Black composers”. Debates concerning “which specific musical sounds and materials would be necessary to make black music”, the newsletter continues, “are no longer necessary. We know that because we are black, we are making black music”.

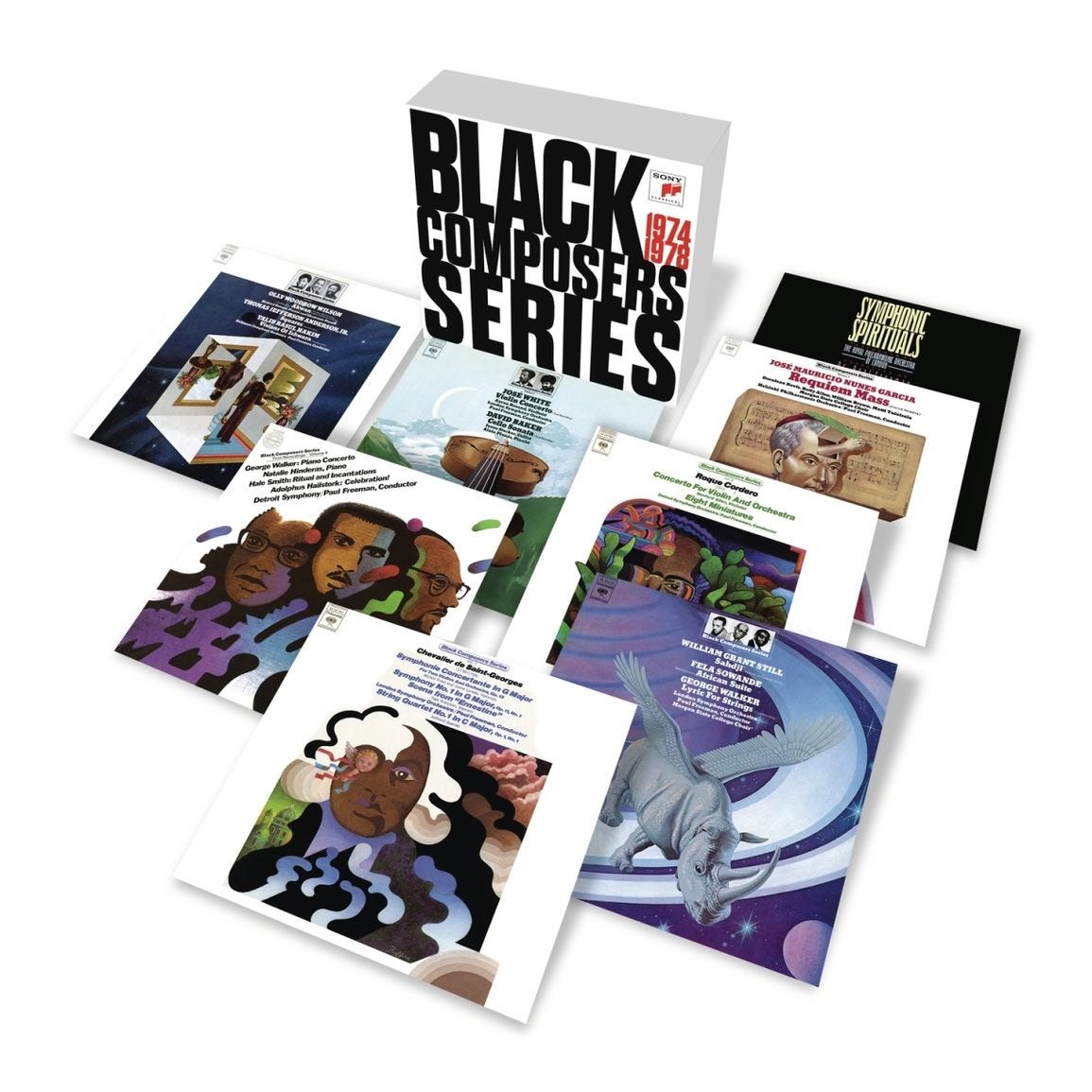

The SBC folded due to funding issues in 1973. But, as Kisiedu warned, we should not frame it through the “trope of failure”. As Eileen Southern noted, when the Society was founded, everyone knew about jazz, but few could have named three or four Black classical composers—if that. By the time it folded, the climate had begun to shift. In 1971, Columbia issued the landmark LP The Black Composer in America, following this up between 1974 and 1978 with the ten-volume Black Composers Series, spearheaded by conductor Paul Freeman. Among other releases, the series—now available in a CD boxset—included an important record of works by SBC composers Olly Wilson and Talib Rasul Hakim—born Stephen Chambers and brother of drummer and multi-instrumental Joe Chambers—alongside T.J. Anderson. Reflecting the times, no women composers feature in the series, but they were central in SBC, amongst them Dorothy Rudd Moore and Tania León.

After the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, Kermit Moore had co-founded the Symphony of the New World, the first fully-integrated orchestra in the US. Eileen and Joseph Southern’s The Black Perspective in Music was founded in 1973, and is today accessible (via institutional subscription) on JSTOR. Eileen Southern’s book The Music of Black Americans, like the Black Composers in America LP, came out in 1971, and 1978 saw the publication of the important book of interviews The Black Composer Speaks. In the new decade, Black composers began to be more extensively commissioned and performed by smaller local groups and major orchestras, while musicians such as Jackie McLean, Archie Shepp, Marion Brown, Bill Dixon and Milford Graves were appointed to teaching positions, often by liberal arts colleges—often, as Lewis remarked, due to the pressure of Black Power student protest movements. Southern herself was appointed a full professor at Harvard in 1976, though, as Lewis noted, she expressed frustration that her white colleagues did not care about her work.

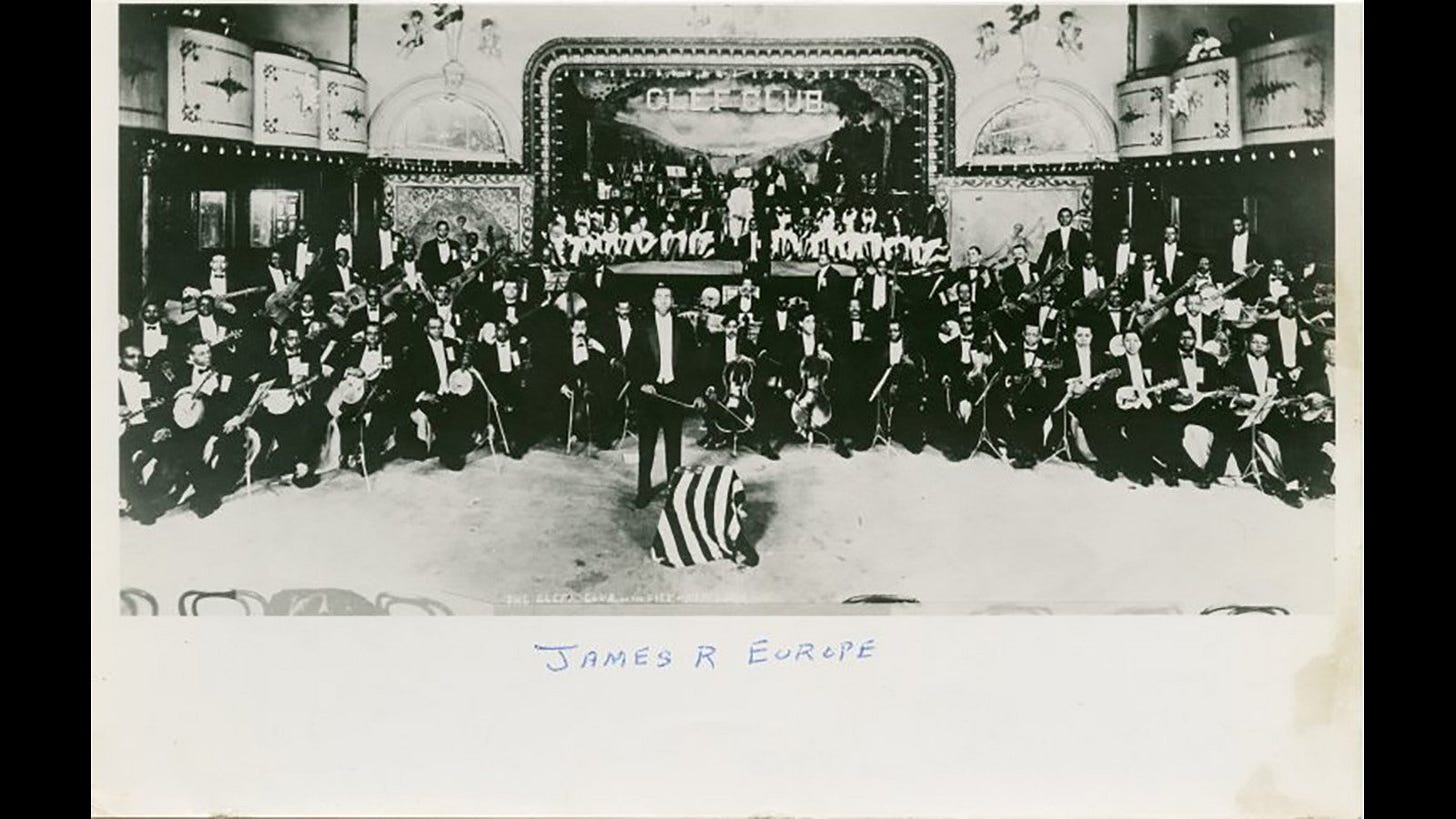

As precursor to the SBC, Kisiedu named the Society for Jazz and Classical Music founded by Modern Jazz Quartet pianist John Lewis in the mid-’50s. One could also date such self-organising efforts back much further, to James Reece Europe, recently explored in Jason Moran’s album and multimedia project From the Dancehall to the Battlefield.

Lewis was notable for his fusions of classical music and jazz, and a concert by the MJQ was largely regarded to have upstaged the premiere of Stravinsky’s Agon at the 1957 Donaueschinger Musiktage (leading jazz to be excluded from the festival for the next ten years). Yet there is also a story by which the mass exclusion of Black musicians from classical jobs, whether that be Charles Mingus’ rejection from symphony orchestras to Nina Simone’s from the Curtis Institute of Music, the latter subject of an excoriating series of works by visual artist Theodore Harris—led to a more creative fulfilment of their ideas in Afro-disaporic composition within the spheres of jazz and popular music.

Some did both: SBC co-founder Kermit Moore appears on records by Ornette Coleman, Yusef Lateef and Robert Flack, among others, Richard Davis with symphony orchestras under George Szell, Leopold Stokowski, Igor Stravinsky, Pierre Boulez, Gunther Schuller, and Leonard Bernstein (and appeared on Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks), and was said to be Stravinsky’s favourite double bassist; Andrew White, who, as a saxophonist, produced definite books of Coltrane transcriptions and numerous self-released jazz albums on his Andrew’s Music label, was also an orchestral oboe player (with the American Ballet Theatre) and Stevie Wonder’s bass player at the same time.

Yet when Black musicians whose reputations were largely associated with jazz worked with white orchestral musicians as composers, they were often met with incomprehension, often because their scores asked players to be more creative than orchestral players are accustomed to being within the hierarchies of classical music. Notable here are the London Symphony Orchestra’s reactions to Ornette Coleman’s Skies of America, and the reaction of the studio musicians hired by Horace Tapscott for the orchestral backdrops to Black Panther Elaine Brown’s second album Seize the Time (Tapscott’s comments come in an unpublished interview with Stephen Isoardi, and the sessions are documented in an as-yet unpublished piece by The Wire’s Pierre Crépon.)

Today, particularly within new music, classical musicians are increasingly more comfortable with improvisation, and such prejudices seem to be fading. Given this, what might have been seen as a kind of necessary ‘double consciousness’ in earlier generations has by now, thanks to years of struggle, given way to the creation of new music that resist such often arbitrary and racialized generic divisions, while retaining the right to lay claims to titles often denied afro-diasporic creators—new music, classic music, and the like.

Five composers took part on the next day’s panel on ‘Decolonizing Electronic Music’, a combination of artist’s- and research-based talks. Making my way back to the Safi Faye Hall, I heard someone whistling ‘Pursuance’ from Coltrane’s A Love Supreme in the corridors. The Haus had begun to feel like home. Corie Rose Soumah talked about unpredictability, “eco-anxieties” and relations to the earth, showcasing a piece involving vibrating shells; Christina Wheeler about the exclusions of race, gender and class that prevent Black artists, and Black women in particular, from accessing the more expensive studio resources available to white composers, combined with the prejudice against the electronic music that Black artists have produced—extensively—within popular or underground experimental musics. And too often, the recent attention to a feminist tradition within electronics has bene almost exclusively white—as Wheeler noted, the much-acclaimed documentary Sisters with Transistors did not feature a single Black artist.

In contrast to the post-war resources available to a Stockhausen or a Schaeffer, historically—and too often today—Black experiments in electronics were based on borrowed time, borrowed instruments, studio visits—Sun Ra’s visit to the Moog studios in 1969, borrowing and never giving back a prototype synth—or those experiments with samplers and turntables that gave birth to hip-hop, and today to Fruity Loops and trap beats. As Christian Wheeler pointed out, the electric guitar is an electronic instrument, and viewed this way, Charlie Christian, Big Mama Thornton or Sister Rosetta Tharpe could easily be pinpointed as pioneers of electronic music as much as Schaeffer or Stockhausen.

In his biography of Sun Ra, John Szwed reports on Ra’s visit to Robert Moog’s laboratories to look at new synthesizers in 1969 (the results would be heard on his recording from the same year, My Brother, The Wind).

He traveled up to Moog’s studios in 1969 and saw his experimental models, one of which was a theremin that was activated by touching a band of metal. Later at a rehearsal, he told the band that when he couldn’t make one of these models work, Moog’s people said that it responded differently to different people’s skin […] One of the technicians showed him a theremin which was activated by touching a band of steel. But it wouldn’t work for Sonny. “The man said, ‘for some people there is a kind of skin resistance.’ In other words,” Sonny said, “for black people, it ain’t gonna play!” […] Then, like a Booker T Washington, he turned the joke into a serious discussion of the progress being made on electric instruments and how he had seen only white people playing at Moog’s studios. “Black people are behind on these things, and they’ve got to catch up.”

The expansive vision of sound found in post-war electronic music—one which expanded the parameters of sound and of music itself—is hardly the preserve of white artists. In her talk, Jessica Ekoumare described the potentials of electronic programmes to move beyond notes and equal temperament, to the potential for every possible sound within the frequency range of human ears, while drawing attention to the presence of sonic innovations supposedly the product of Western avant-garde in ‘pre-modern’ music: for instance, the presence of combination tones and of melodic distribution among multiple parts without voice leading, in music of the Baka people. Ekoumare also made links to a broader process of musical homogenisation also taking place in Europe, whereby the exclusion of instruments not part of standard tuning from the orchestra formed part of a process of suppressing regional customs and languages that would be extended to the colonies, noting her work for traditional instruments in France, such as bagpipes and hurdy-gurdies.

Noting the origin of computation outside Europe—the invention, for instance, of the algorithm by Persian mathematician al-Khwārizmī—and the ways in which innovations from outside Europe now fundamental to modern systems were initially perceived as a threat—for instance, the introduction of the Arabic 0 into Europe as threatening the base of Christianity, because it was seen as introducing the theologically-problematic trope of nothingness—Ekoumare argued against histories of electronic music that begin and end in Europe, with a move towards abstraction as goal, and that end in a place with no political backdrop.

Such accounts are the standards ones by which electronic music begins with Pierre Schaeffer and the GRM in 1948 and not with Halim El-Dabh in 1944 and the piece Ta’abir Al-Zaar (The Expression of Zaar). Indeed, this came up again and again in this and in other panels: the number of times that Schaeffer was cited as founding electronic music in the post-war Stunde Null. (The next day, Nyokabi Kariũki noted, for instance, that she spent an entire semester at IRCAM in 2018, during which El-Dabh’s name was not mentioned once.) This myth takes place alongside the myth that Darmstadt or Donaueschingen or Princeton and other centres of Western European new music were entirely absent of creators of colour or creators from outside Europe’s borders.

While western institutions were generally dominated by white men, as now, there were others always already there. The Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center was not just Milton Babbitt and Charles Wuorinen but El-Dabh, Chou Wen-chung, Halim El-Dabh, Michiko Toyama, Bülent Arel, and İlhan Mimaroğlu (the latter of whom later worked with Freddie Hubbard on the anti-Vietnam Song me a Song of Songmy, a little known early example of electroacoustic collaboration with jazz musicians in the late ’60s). (We could also name Isang Yung at Darmstadt, the formative influence on Luigi Nono and Bruno Maderna of communist Brazilian composer and subsequently ethnomusicologist Eunice Katunda’s study of Afro-Brazilian music, and the long-running jazz component of the Donaueschingen Musiktage.)

This myth—what Lewis (following Dana Reason Myers) terms “the myth of absence”—is accurate in that it reflects the institutional and discursive structures which reinforce an idea of a white avant-garde as norm, leaving the capacity to innovate to whiteness and seeing everything else as aberration nor imitation. But it is hopelessly inaccurate as a historical account of what’s actually gone in music. As Leila Adu-Gilmore noted in her presentation, acts of “radical reclassification” are needed to force such recognition (Gilmore prefers to use the term “Northern European Christian harmony” to ‘western’ or ‘tonal’ harmony in order to re-provincialize it.)

Another tactic is simply to make information available. Traveling and performing across the world, collaborating and documenting artists from numerous different countries, Cedrik Fermont’s work has been exemplary in this regard. Fermont’s online database of electronic music from the African and Asian continents, divided by country, is ever-expanding, and freely accessible on his Syrphe website.

As a collector, Fermont makes an important point: it’s not as if this work was not already documented, sometimes by major record companies and in major institutions. He named, for example, Hugh Davies’ vast International Electronic Music Catalogue from 1967, which includes work from Eastern Europe, South Africa, South America and Japan. But historical memories tend to be shorter when it comes to creators who are not white: hence the need to remind people that material is out there, in albums, compilations, books and other resources, and more accessible than ever in the age of the internet. Someone in the audience was reading Kwame Nkrumah’s Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare. This is not exactly the same kind of decolonisation as databases and albums—but then again, it isn’t not.

Whether acoustically or electronically, inventing or extending instruments as a part of Afro-diapsoric creativity—from the radical refiguration of the saxophones or the creation of the modern drum set to autotune—to Africanize European instruments, to fuse.

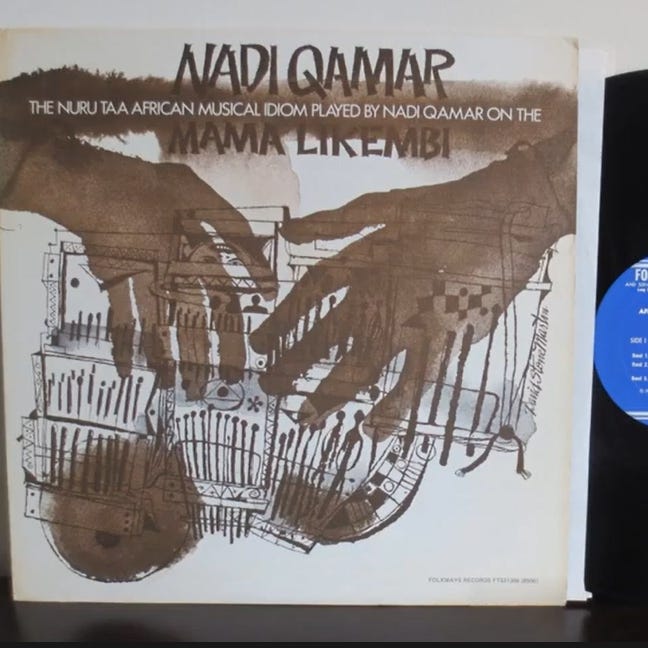

Christina Wheeler plays the array mbira, Bill Wesley’s giant mbira. Also worthy of mention in this field is Nadi Qamar—who died aged 103 in 2020. Also a jazz pianist and composer, Qamar recorded with Charles Mingus in the ’50s and Andrew Hill in the ’60s, and on the soundtrack to Bill Gunn’s Ganja and Hess in the ’70s, before recording a series of lecture-demonstration albums on his own invented lamellaphones for Folkways records. Before Wesley, Qamar invented another super-kalimba, the Mama Likembi, which a writer at the Kalimba Magic site describes as a ‘neo-traditional’ instrument: “By neo-traditional, I mean that even though the instrument was not a traditional kalimba in a traditional kalimba tuning, Nadi was creating his own tradition that symbolically points back to the rich African musical traditions that he had been cut off from through his ancestors forcible patriation to America through the institution of slavery. Jazz itself is like a new-traditional musical form.”

In George Lewis’ own Homage to Charles Parker, contact mics on cymbals pick up Parker’s vibrations. El-Dabh’s own electronic music came from a fusion of modern technology—he’d been researching electronics as part of his work as an agricultural engineer, trying to make sounds that would keep insects away from crops—and his desire to document the ancient tradition of the Zaar or Zār, a public ritual of possession taking place on the street. The binaries of modernity and tradition, East and West, and all those other supposed oppositions used to justify various forms of white supremacy, are subverted, fall away. Sometimes the sound of the future comes through as the sound of the past, and the sound of the past as the sound of the future.

Day Four’s panel focused on African Art Music, a term the contributors immediately problematized. As moderator, South African composer Andile Khumalo noted, historically, Christian missionaries imposed western music on colonized countries to stamp out what they perceived to be ‘demonic’ or ‘barbaric’ cultural practices, establishing an opposition between the ‘civilized’ and the ‘artistic’ and its others that persists to this day. In one of the characteristically cruel paradoxes of colonisation, the Church became a place of refuge from the more overt horrors of colonialism: in South Africa, for instance, the police wouldn’t enter churches, but would brutalize people on the street. To make music was to make music in the church, as Black people were largely excluded from university settings, leading to the development of choral composition, in which western hymns, their European words rewritten to fit indigenous languages, were also subtly altered musically through the inclusion of Africanized vocal stylings such as glissandi resembling speech patterns and call and response—in some cases, enacting musical tropes for which musicians could have been arrested outside the context of church music. African classical music was thus of necessity hybrid, and inasmuch as the African continent itself contains numerous separate nations, cultures, and ethnicities, all with different musical traditions.

As Njabulo Phulinga explained, the concept of ‘art’ music relates to legitimacy conferred by certain types of classical training, automatically establishing a hierarchy with folk or popular traditions. While African classical composers thus participated in a music constantly at odds with the conditions under which it was presented, even as they were forced to seek validation from those conditions.

On the one hand, the modes of knowledge already present in African musics were systematically excluded from the canon of legitimacy. Attending school in Kenya, for instance, Nyokabi Kariũki noted that students had to describe snow an exam despite never having experienced it. (Recall Kamau Brathwaite’s famous anecdote about the Caribbean child writing an essay with the absurd, impossible image of “snow “falling on the cane fields”, thanks to a colonial education.)

On the other hand, African composers, like African-American jazz musicians, have often been expected to refer to recognisably ‘African’ traditional subject matter to earn legitimacy. The reality, however, is that the experience of Africans on the African continent, like that of African-Americans, is by its very nature hybrid. African art music, or, to use a less loaded term, contemporary or new music, could thus be defined, not by its subject matter or even, necessarily, its musical techniques, but by its intention, or what Phulinga called “cultivation of a musical medium in the context of the gatekeeping in African institutions focusing on western music”.

Njabulo Phulinga and Andile Khumalo live and work in Africa (Phulinga in Durban and Khumalo in Johannesburg). Often, however, the African composer has to travel to seek wider recognition and opportunity. On Zoom, Monthati Masebe, now studying at Duke, reflected on the problem of “what happens when an African artist moves abroad and comes with their music”, and the need “to be both globalized in taste and localised in palette.” During a European residency, Phulinga noted, he had presented a piece with no specific reference to his cultural background. It was African because he is, as the Society of Black Composers noted about Black music.

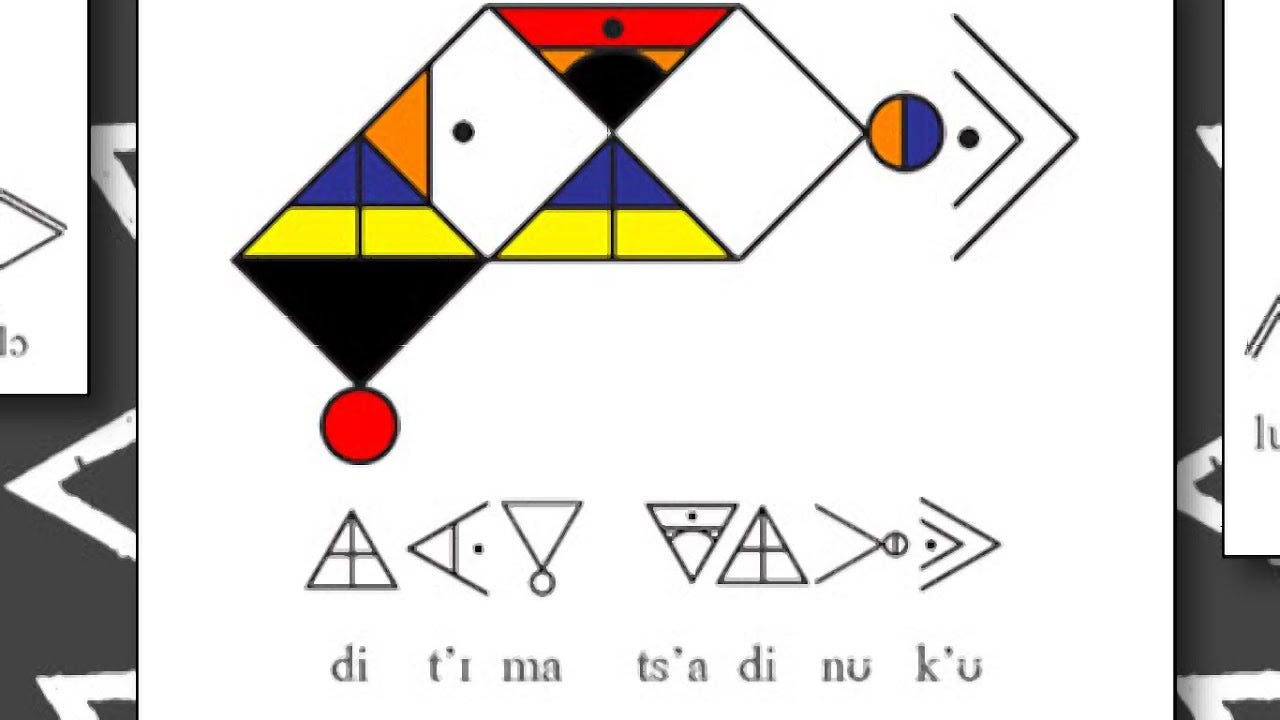

On the other hand, in moving outside Africa, Masebe noted, the desire is to avoid simply presenting a reified image of the continent. In this regard, Masebe noted their own attempts to draw on the harmonies present in traditional throat singing, in which key changes are not signalled at particular points, but transitioned towards more gradually, along with the de-prioritisation of fixed meter in favour of asymmetric pulse. In their work, Masebe suggested, they try to keep these divisions as a source of visible and productive tension—for instance, in figures which move against, rather than with barlines. Elsewhere, they’ve developed a form of graphic notation influenced by the Ditema tsa Dinoko, a modern-day Sesotho syllabary developed in South Africa for the siNtu or Southern Bantu languages. SiNtu languages are tonal and rhythmic, and this reflected in orthography which, while linguistic, also indicates mouth position and syllable expression in ways that bring it closer to music notation.

Nyokabi Kariuki, meanwhile, noted the ways that contemporary African electronic musics develop outside official institutional sanction in Kenya, such as The Mist in Naoribi, which takes place in the abandoned basement of a shopping mall. “Culture”, she observed, “bubbles up in places people choose to turn away from”, “springing up outside institutional spaces that determine memory and who gets to be remembered”. Today, African music is increasingly making itself felt worldwide, in the development of Afro-beats and in the African influences heard in the work of second-generation musicians growing up in Euro-America. (Aya Nakamura, for instance, is currently the most listened-to French artist in the world.) Focusing on African composition—whether we term it African contemporary music, African art music, African new music, or some other as yet-undetermined term—also shows another side to African music beyond either traditional or pop musics, deepening both our sense of African music as a whole and of classical or new music.

Thursday saw the incubator’s first concert, titled, like the previous day’s panel, Decolonial Electronics. Corie Rose Soumah’s States of Intermeshing: Smoke made full use of the Miriam Makeba Auditorium’s surround-sound system, as a series of crackling sounds (the smoke of the title?) emerged as if from the back or the top of our heads. A two-note figure gradually emerged to serve as a kind of ‘bassline’, surrounded by whooshing, static, phaser and other effects, before fading out again. Satch Hoyt’s Oblation Un-Muted featured members from the International Contemporary Ensemble intertwining alongside Hoyt’s own playing of a table chock-a-block with percussion and other instruments, from cuíca to slide whistle, with projections of Hoyt’s paintings—‘Afro-sonic maps’ that resemble vévés, speakers, and celestial objects—and Hoyt recited a poem which spoke of the need to “go beyond layers of apologetic tokenism” as the music build up to squalling trumpet and bass clarinet.

The weekend before, I’d seen Fay Victor’s extraordinary performance of Herbie Nicols song at the Jazz Keller over in Schöneweide. As this concert proved, as well as one of our finest jazz singers, Victor is superlative interpreter within a new music context. Working with percussionist Levy Lorenzo, who modified her imput with joystick electronics, Victor moved between ‘abstract’, wordless vocals to a poem which imagined a world where the time taken for activism could be taken up instead by doing things that “bring joy”. The imagination of utopia was expressed as speech, as something ‘non-musical’, an interruption: the move from discourse to enactment, ending on a wordless syllable that breaks out of and emerges from language, hanging there, an unanswered question.

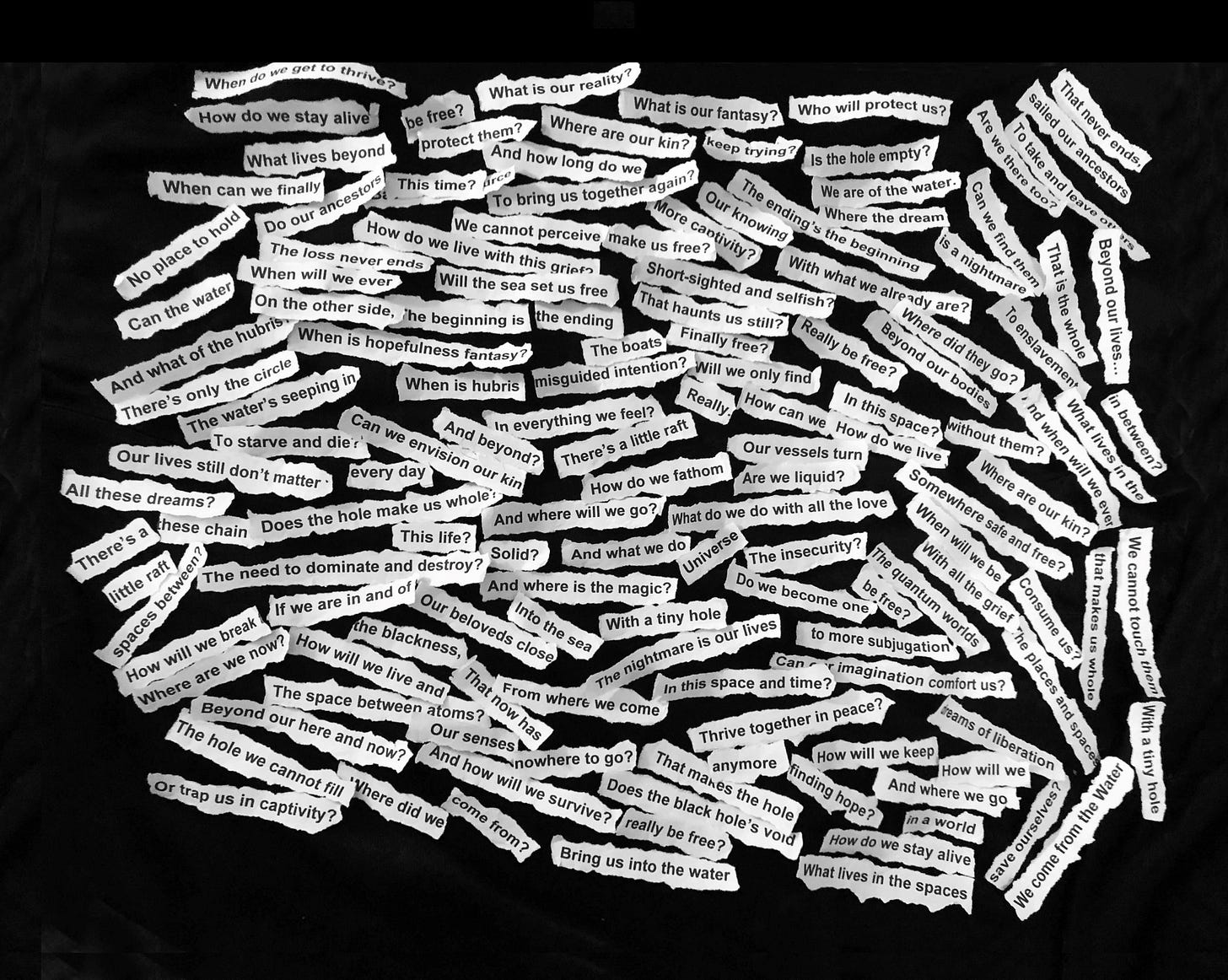

In Cedrik Fermont’s solo Point of Convergence, channels faded in and out of each other, pitch-shifting sine tones, crackles, whooshes, what sounds like the occasional fragment of a voice: sounds always on the verge of explosion, or emergence, which—as per the piece’s concept around an indecipherable language, or a kind of anti-lingua franca—never quite seemed to fully emerge. The evening ended with Christina Wheeler’s From the Quarter to the (W)hole: A Prelude, with Wheeler—on kora, mbira, balafon, and voice—onstage alongside members of ICE. A series of questions—‘who are we?’, ‘where do we come from?’, ‘where are we going?’, ‘when will be free?’—are spoken and sung as recorded percussion and slow ensemble melodies fracture and spiral into overlapping lines.

As the weekend approached, activity at the HKW increased, with the Saturday alone including two panels followed by a concert, a solid five hours of activity. Friday began with a panel on interdisciplinary featuring Douglas Ewart, Anthony R. Green, Satch Hoyt, Nyokabi Kariũki, and Elaine Mitchener. Mitchener spoke of work with dance and choreography, and turning what would have been a vocal gesture into a physical one in a recent piece on fast fashion performed at Somerset House. Speaking about the “sharing of experience” involved in such collaborations, and quoting Eastman—“music is only one of my attributes”—she noted that “I don’t know any other way of working but interdisciplinarity”.

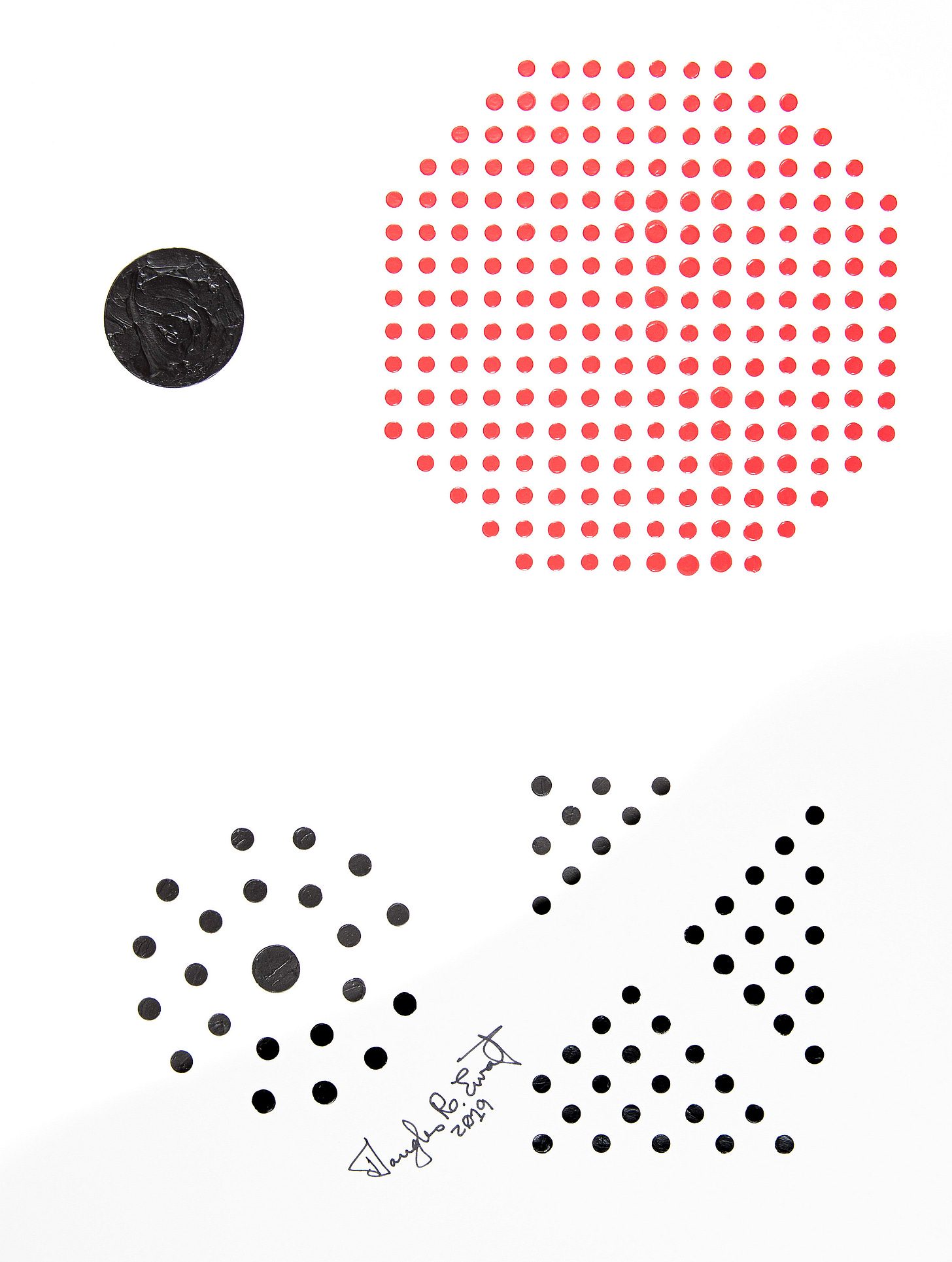

Within this concept of interdisciplinarity, even the framework of ‘composition’ or ‘composers’, so often a racialized one, is one to be challenged, or expanded. A composition might involve the facilitation of a group endeavour through built instruments, as in Ewart’s work—the division between craft and art practices. Mitchener talked about choreographic movement as the extension of vocal gesture, Hoyt about paintings as graphic scores and visual representations of sound, and Kariũki about planting trees. We might think back too to the 1950s, to the recently-passed poet-composer Russell Atkins and his concept of ‘psychovisualism’, or to the 1960s and Ben Patterson, trained as a classical musician and working primarily as a visual artist.

This fluency is one which, in the context of Afro-diasporic music, we should increasingly see as norm rather than exception, and which, indeed, we might see as a condition of musicking per se (to use Christopher Small’s term): it’s only in the divisions fostered by a certain attitude to classical music—the division of composer and interpreter, score and sound—that interdisciplinarity is not fundamental. Following Shawn Wilson’s argument in Research is Ceremony, Nyokabi Kariũki argued that knowledge is “relational, not individual”.

Kariũki’s presentation focused on a project in which she travelled back to her parents’ region in central Kenya to work on a project on trees, which involved learning Kikuyu. “To switch language is also to switch world view”, she argued. Anthony R. Green outlined some of his numerous projects, involving his work as vocalist, pianist, and performance artist as well as composer, while Hoyt spoke about his trajectory from theatre to visual art and thence to music, and his current projects recording what he termed “incarcerated” African instruments within western ethnographic museums, using these recordings to insure that, even if the instruments themselves are kept separate from any functional use, their “spirits” might be kept in the room.

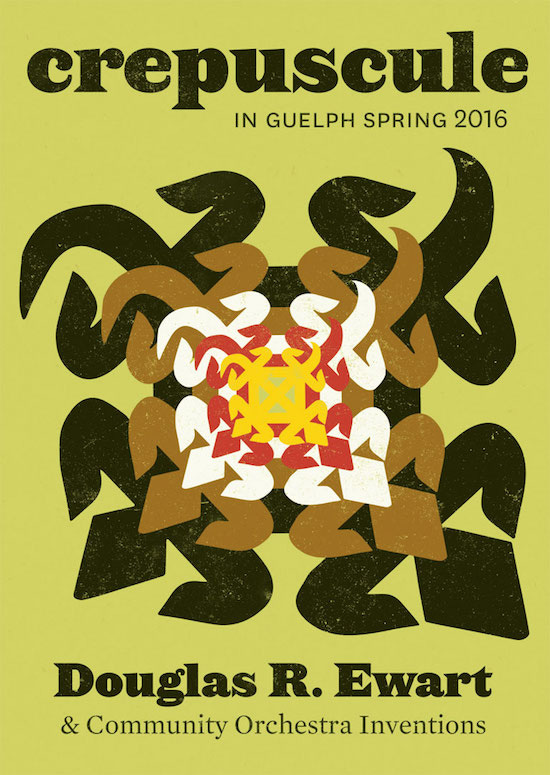

Douglas Ewart began with his childhood in Jamaica, recalling building his own toys as a child and writing his first song, a blues, about the strike-breakers sent into Harbour View, before speaking of more recent community projects involving spinning tops and other constructed instruments such as the George Floyd Bundt Staff (Ewart lives a few blocks away from where George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis and played these instruments on the street during the 2020 protests.) There is, he noted, a gatekeeping, racialized hierarchy which establishes a distinction between ‘art’ and ‘craft’. But for Ewart, his practice as craftsman, instrument builder, and musician is inseparable, stemming back to that practice of building developed as a child.

Likewise, Ewart’s work as a musician is inseparable from its community function: his piece Crepuscule begins with a gathering by a tree or water, as different ensembles drawn from the community embark on a parade, with the entire community, from young children to elders, represented, along the lines that “the individual helps build community and the community helps build the individual”. The AACM School, as he noted, was a fundamental part of its work, but this is not simple about formal training: the way an ordinary listener absorbs music on the radio or in daily life is equally a kind of training, and, as a musician, by “remaining supple like a child, you absorb and you return to absorption”.

Such work may arise by necessity—when Ewart first arrived in Chicago, he was unable to afford a conventional flute, so built his own, eventually making them for others and selling them at art fairs. Importantly, Ewart likened this to the “multitudinous work of mothers”—the fluid multitasking so often required in a society where the burden of household labour, childrearing is placed on women. ‘Community’ is not just a general buzzword, but something deeply entwined with gender roles, with racialisation, with the work of survival and transformation. For some, interdisciplinarity is not a choice. But it is also an opportunity, to generalize the skills so often demeaned or delegated to others, across the community as a whole.

Following the panel, a concert entitled Composing while Black took place in the Makeba Auditorium. The longest of all the concerts, it featured no less than nine composers and lasted something like two hours. With each composer allotted slightly longer pieces, this alone might have formed the basis for an entire festival.

The soundworld of Alyssa Regent’s opening Emergence was set by a prepared violin bow, creating a friction in its movement over the string to set off various partials and other extended effects, over which the rest of the ensemble offered slow held notes, multiphonics. Conventional ways of producing sound are impeded, and thus extended, its course altered from the norm so it can flow.

In Nyokabi Kariũki’s The Color of Home, Levy Lorenzo performed on a table of percussion instruments, over a film juxtaposing shots of clouds, grass, dew, birds and skies with multi-lingual recordings with the immigrant parents of various US-based musicians reflecting on the concept of home, the difficult of arrival and of starting afresh. The solo percussion part, and recorded electronics featuring the treated and untreated sounds of violin and zither, didn’t so much translate or accompany the interviews as exist alongside them. Perhaps the most potent part of the piece, both musically and sonically, were the two large jugs which Lorenzo played with mallets, periodically transferring varying amounts of water to vary the pitch. And this ended up being the final action of the piece: the movement of the large into the small, the transfer from one medium to another, voyages and returns and flows.

William Parker has called Jalalu Kalvert-Nelson “one of the unsung heroes of music in the 20th and 21st centuries. The quality and scope of his work are, for me, on a par with Ornette Coleman and Duke Ellington”. Nelson studied with Xenakis, among others: today he is perhaps less known than others because of his long-term residence in Switzerland. His Rotations III combines composed music for bass clarinet with a combination of improvisation and composition for the trumpet part (Nelson is himself a trumpeter: that role today was taken by ICE’s Jonathan Finlayson, himself an excellent jazz musician). The piece is a fascinating aural experiment that finds new ways alongside the strategies for combining the two found in by now tried and tested formats such as text-based, aleatoric or graphic scores. Above all, it’s good-natured: fun, lively, dancing with ideas.

Leila Adu-Gilmore’s Freedom Suite takes up the mode of what used to be called ‘art song’. Lines and rhymes spin out in careful constructions that approach music theatre before spinning into prosaic extensions and harmonic dislocations closer to new music, all smoothly enacted by Gilmore herself on voice and piano alongside the ensemble. At times, words and music join in smooth, extended melodies, at others, strain with deliberate awkwardness against the rhythm, as ways of reflecting on the ways song carries meanings of various kinds. In the first song, for example, there’s a particularly painful rhyme on the potential respective fates of teenage encounters with police across racial lines—“sent home in a bodybag” and “wind up as a college grad”—music and text enacting the cruel joining of discontinuous experiences to chilling effect.

The title to Andile Khumalo’s piece for solo piano, Schau-fe[r]ns-ter II puns on the German for window display—Schaufenster—and the phrase aus der Ferne schauen—to look from afar. (In German, to look and to show are the same word.) Something of this ambiguity makes it way into the piece. Onstage, an image is projected from South Africa’s apartheid history, of a child holding the body of another, murdered child, running towards the camera. What does it mean to look from afar, or close up? How is the viewer or listener placed? (These issues assume particular, painful relevance today as we see daily massacres enacted on TV and computer screens while politicians continue to deny that anything is amiss.) In the piece itself, repeated high notes contract and merge with taut flourishes, sustain-pedaled tones sounding out into silence: a kind of call and response not only with the notes themselves but with the silence surrounding them.

Charles Uzor’s Elegy for Marianne Schatz, for violin and electronics, was dedicated to the classical patron who’d asked him, some years before, to set newly-rediscovered poems by her “long-dead childhood-sweetheart”, a task he’d had trouble accomplishing before her death. Motivic features seem to catch themselves as they repeat, elongating or altering each time; the sudden entry of recorded Hindewhu, the single-tone Ba-Benzélé flutes made famous through the 1966 LP recorded by ethnomusicologists Simha Arom and Geneviève Taurelle, fade in and out, revealing their scalar relation to the violin’s scalar material. Rather than signifying African roots (born in Nigeria, Uzor came to Switzerland aged seven due to the disruptions of the Biafran War), they are, he observes in the programme notes, from a place whose language he does not know, interrupting as much as explaining, opening up an alternate space in the music, unknown, experience as a sonic object, matter out of place, that yet forms its basis. Referring to Schatz’s commission, Uzor calls the piece “the testimony of an attraction that hovered over the hurdle of strangeness […] what is (not) mine, who do I belong to (not)?”

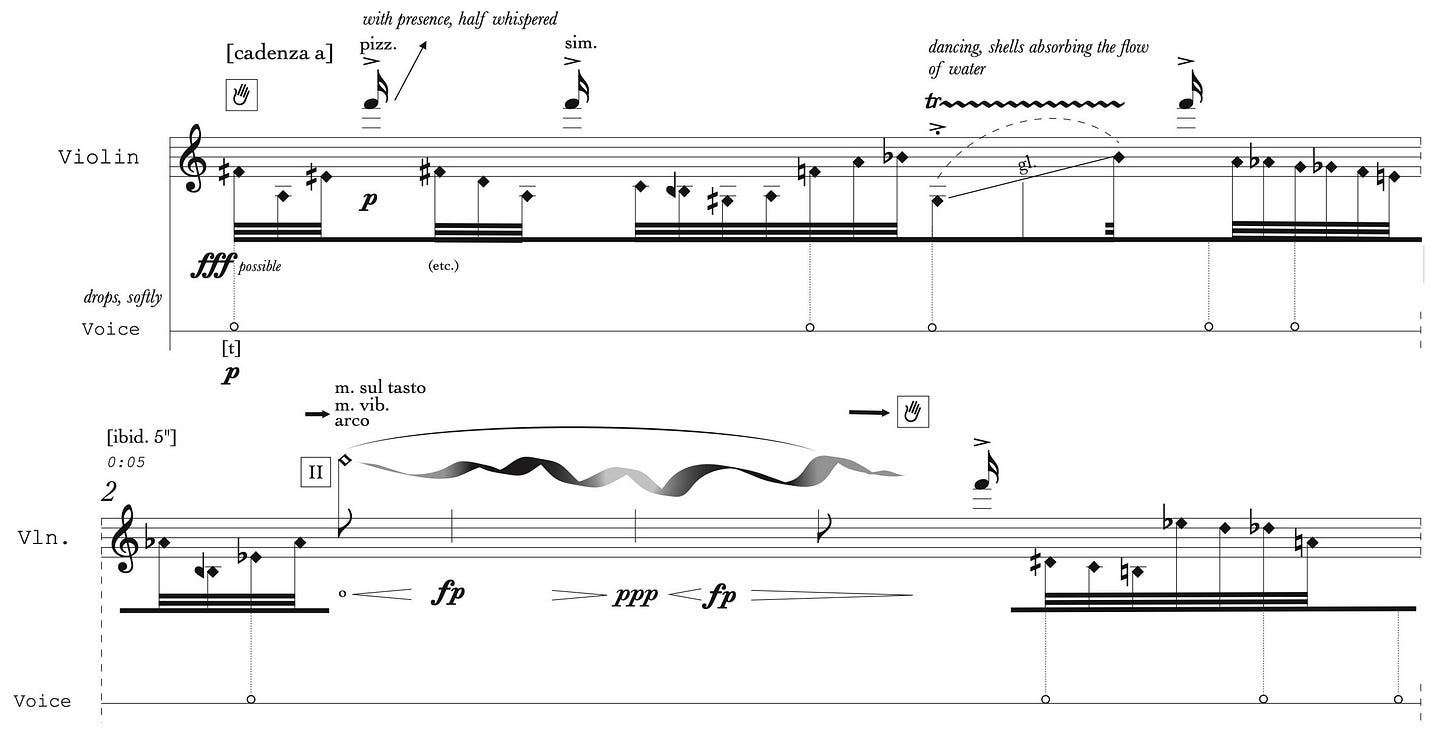

Powerful as all these works were, to me, the most impressive pieces on the programme were those which delved closest into fundamental assumptions about what new music is and how it might be performed. Corey Rose Soumah’s limpidités IV for solo violin mics up the soloist—the astonishing Caitlin Edwards—with an amplified voice part propelling, interrupting and interacting with a highly virtuosic (but by no means flashy) instrumental line. Something like a scored version of the humming famously practiced by performers from Glenn Gould to Sunny Murray, the performer’s vocal interjections and whispered expulsions, function as rhythmic punctuation or set off pizzicato scuttles down the fingerboard. The work very carefully alternates sound areas—moments of jagged delicacy alternating with seesawing bowed figures, a held chord wavering into partials—in a kind of slow juggling, as ideas come back or disappear. As a passage of unpitched bowing seemed to transmute the violinist’s breath, we in the audience held ours. Before the concert a friend told me about the way a ballet dancer leads with their hand, the gesture shaping where they’ll go next: the hand shaping thought. And, in ways not quite like any other piece I can think of, the work draws attention of to the performer’s body and its relation to sound production, in ways that our habituation to more conventional forms of virtuosity perhaps too often inures us to. (The debut recording of the piece by violinist Gillian Smith is below.)

Hannah Kendall’s when flesh is pressed against the dark, its title, as in a number of her recent works, taken from Ocean Vuong, for voice (Damian Norfleet), trumpet, trombone and bass clarinet, continues Kendall’s exploration of the histories embedded within musical instruments, musical references: music boxes that play melodies of particular resonance during the time of the slave trade, harmonicas, with their associations with the blues, walky-talkies, their closed system echoing Cuban writer Antonio Benítez-Rojo’s writing on what he calls ‘the plantation machine’.

All four musicians begin on harmonicas, a held rhythm of breathing, a fortissimo falsetto erupting like a sudden cry, before Norfleet mutes the sound by covering his mouth with his hand, then sings a deep croon into two walky-talkies that feed back into each other, gently. It’s as if singing up against something, muffled, muted, the transmitting device that feeds back into itself, that mutes as well as amplifies. For much of the piece, at least one musician can be found playing a harmonica while the others quietly or with sudden blare hold muted or open notes, split open into multiphonics, smearing and trilling upwards, high and strained, against the registral grain, now getting quieter and quiet, never quite fully fading, walky-talky feedback merging with harmonics and painfully, deliberately held. Gently humming along, Norfleet winds up a music box which plays the hymn ‘Then sings my soul’ into the silence. Within the extensive, open-plan space of the Makeba Auditorium, the quiet tension is palpable, and the moment is profoundly moving. (The premiere performance of the piece by ensemble loadbang is below.)

To close the concert, Jessie Cox’s (Noisy) Black/blackness (unbounded) introduced a palpable energy that moved into the energies of other forms (Cox is himself a drummer and has performed in free jazz contexts), somewhere in the borderlands between composed gesture—most notably in the form of unison vocal entries from Norfleet and Fay Victor—and something that seemed closer to the flows and assemblages more often associated with improvisation. Norfleet moves effortlessly from eerie falsetto to guttural, swooping growls, as the instrumentalists dash through quick bursts of muted scurrying or broken melody, a violin scratch, a trumpet breath. The ensemble builds to a particularly dense intensity seemingly on the edges of fortissimo, before a trumpet blast echoes a cut-off vocal yell and the piece ends.

Paradoxically perhaps, in all these pieces, the moments where the music came closest to silence were the most charged, particularly in the vast space of the HKW auditorium. These, it felt, were the moments where one might most deeply interrogate all the histories swirling and around the music, at the point where it itself had almost disappeared. A point to assess where we are; a point from which to begin again.

Day 6, Saturday, and a discussion on curation was followed by the first of two ‘Composing While Black’ panels on the individual practice of particular composers involved. Daniel Daude, founder of the String Archestra and ComChor, who performed on the final night, offered important perspective—surprisingly often ignored within the English-leaning international art scenes of Berlin—on the specific experience of Afro-Germans, noting a lineage that goes back to the formative anthology Farbe Bekennen (Show Your Colors) edited by May Ayim, Dagmar Schultz, and Katharina Oguntoye, and that includes Oguntoye’s intercultural network Joliba—formed in response to the racial violence of the early ’90s, a time when neo-Nazi and anti-immigrant rhetoric forms disturbing parallels to today. As Duade noted, her ensembles have often operated outside the traditional institutions for classical or new music: the conductor-less Archestra, for instance, organises a regular night in a Kreuzberg punk venue, emphasizing music by Black musicians as part of an already-existing community practice, rather than trying to force one’s way into the often indifferent and even hostile settings in which such music is more often heard.

The problem, Elaine Mitchener agreed, is persuading institutions to take the steps to programme music, especially experimental music. Cedrik Fermont, speaking of his experiences co-organising electronic music workshops for female composers from Asia and Africa at the Darmstadt Summer School, made the important point that, while there is much talk about race and programming, there’s less about the practical issues of money and, especially, visas for artists from the Global South, the barriers of entry fees and ticket prices. Both Fermont and Duade emphasized the need to conceive of new music outside traditional spaces, while Mitchener noted that, even when performing within traditional spaces, one might seek to “test” them, transforming them from within. As chair Leila Adu-Gilmore put it, this process might involve “being a double agent”, bringing new music into experimental spaces, and experimental music into new or classical spaces. Ultimately, the participants agreed that the situation won’t change if the boards, directorships, and most of the positions in the major classical institutions are still almost universally white and mono-cultural. That HKW is now run by Bonaventure Ndikung, and that the events took place here, rather than a more traditional classical venue like the Philharmonie, is indicative. To build community must be collaborative, but change, if it’s to come, must also come at the top as well as from below.

On the composer’s panel, Hannah Kendall spoke about her practice of ‘creolizing’ western orchestral instruments through preparing them with dreadlock cuffs. Because the cuffs slide up and down the strings of a violin or harp when they’re played, these sounds are inherently unpredictable, a figure, in turn for the kinds of intercultural encounters this practice can foster, as when a Finnish collaborator went to an Afro-shop in Helsinki to purchase cuffs for a piece. Njabulo Phulanga talked about Borges’s infinite library and a ‘corridor’ method of composition in which sounds were perceived as rooms coming off a floor, rather than according principals of linearity and development.

Anthony R. Green’s talk on the US election result and the daily racism faced ‘composing while Black’ hit home the obstacles that exist before even beginning to compose. Monthati Masebe likewise spoke of the political dilemmas faced in South Africa, where politicians have profited from decades of struggle while the majority of people have not, and where classical music often distances itself from those who want to be politically progressive, “pandering to whiteness”. Likewise, in the US, her cultural background is often misunderstood: “you have to fight for your own voice even when you’re provided with a platform”. Noting the growing apathy towards corrupt or authoritarian states in African countries, Masebe described themself as too connected to South Africa to be diasporic but no longer living there; of the necessity of maintaining the idea of blackness as oneness while registering the reality of political divisions. For his part, Jessie Cox, also acting as moderator, placed his work in the lineage of Richard Iton and Fred Moten: “to reimagine the world—that’s what music is to me”.

The evening’s concert featured the work of Douglas Ewart, performed by International Contemporary Ensemble with Elaine Mitchener, Damian Norfleet and Fay Victor on vocals alongside Jonathan Finlayson on trumpet, Rebekah Heller on trombone, Joshua Rubin on bass clarinet, Jakob Greenberg on piano and harmonium, and Levy Lorenzo on percussion, with Ewart himself selecting from a table of instruments or reciting poetry.

The concert opened with the deep unison of bass clarinet, bassoon and trumpet playing a melody that didn’t stop, a single line, or perhaps more accurately, a spiral, one line bending, weaving, waving into other lines, other forms: a prelude, elegant, ruminatively buoyant. A text against plastic bags and environmental waste ushered in the vocalists, before Ewart conducted in a lively-urgent, march-like melody and words on “the concentric rings of trees” as a metaphor for connection—“related yet autonomous”, “embracing yet unbridled”, “complex like the rings of Saturn”, these rings set off against the apparently “ceaseless” war machine, the production of weapons opposed to the comradeship. “We are compelled”, Ewart recited, “to go beyond tolerance to coexistence, / in order to survive and to thrive / the human family. Evolution / Revolution / Resolution”. The ensemble volume rises and falls as Ewart switches instruments, from didgeridoo to bird whistle, a large shaker rustling like water or shells, a self-constructed flute; then, cued by a massive gong blast, Ewart’s circular-breathed sopranino saxophone blows up a maelstrom as the collective voice rises, blasting away, ending with a final trio fanfare recalling the opening.

The form of the music performed was, as far as I could tell, essentially modular: there were unison melodies that could also be picked up and varied during group improvisations, and poetic texts that could serve as the basis for vocal extension, as well as clear starting and stopping points from various pieces, but the music was intended to flow as a whole, and could change on a whim. Towards the end of the set, Ewart started handing out new scores to the musicians, forcing them to think quickly on their feet, while other pieces that had been rehearsed were apparently not performed. As with the scores of Cecil Taylor, perhaps, rehearsal is not just a chance to perfect the interpretation of fixed music, but of thinking one’s way into a musical space that might, on the night, be realized by playing completely different music.

As such work reveals, the distinction between composition and improvisation, or between kinds of composition and what counts as real composition, reinforces hierarchies that also denied the lived reality and experience of the way that many musicians actually make music, or restrict the possibilities for others trained to dismiss such crossovers and not to develop such skills. Expanding the idea of the composer and of composition to also include performing, co-creating, making and inventing instruments—as Douglas Ewart does—or writing in its various senses could change our idea of what music is.

Day 7: Sunday was the final day of what had been a whirlwind of events. Having begun the week with a heavy flu, through which I’d struggled to drag myself to the panels, by now I was approaching something closer to lucidity. The final discussion, a second ‘Composing While Black’ panel, featured Andile Khumalo, Jalalu Kalvert-Nelson, Alyssa Regent, Corie Rose Soumah and Charles Uzor. Khumalo talked about the segregation fostered by Apartheid, and its continuing effects in South African musical education, speaking of his experience in the largely jazz-based Siyakhula programme run by Brian Thusi in the 1980s and in the Salvation Army Band, and about the need to view music as “more than the geographic representation of a person”. Timbre, he suggested, might be one place to do this, allowing one to lose the identity of the instrument playing—that’s to say, the idea of what sort of thing that instrument is supposed to play—and to focus on the sound itself.

Alyssa Regent spoke about juxtaposing settings of poems by Louise Labé with recordings of Audre Lorde. The genial Kalvert Nelson—who observed that “last time I was in a gathering of Black composers it was in the 20th century”—talked about “standing on the shoulders” of those who’d come before—among them George Walker, Olly Wilson and Hale Smith, in order to move “into the stratosphere”, before discussing a recent piece entitled ‘Jim Crowing’, and the way his work bridges conventional notation and improvisation. As he put it: “I try to improvise like the music is being composed before your ears, and I try to compose as if the music is being improvised before your ears”. Corey Rose Soumah spoke of biraciality as a form of life, of hybrid graphic and traditional notation, and of composition as a process of layering: while the first idea may, in fact, be the best idea, it must be “overwritten”, sound treated as blocks to be moved rather than the linear following of ideas.

Charles Uzor offered an intriguing ‘Berlin Manifesto’, largely read out by an automated voice, with Uzor occasionally echoing live, full of playful contradictions which he gracefully refused to explain. (Manifestos are, he noted, “a bunch of contradictions banging on your door.”) Among other things: “repetition is a melodic necessity”, “twelve tones are deficient since they express bourgeois values”, “we admire Alban Berg when his structure crumbles in its sensation”, “the vocal is an act of intersubjective mercy”. These elegant paradoxes where perhaps as good a place as any for the discursive part of the incubator to end, offering multiple paths to be discarded, or taken up. But perhaps most pressing was Kalvert-Nelson’s post-US election warning in the Q&A: “we will have to fight for our creativity, which means to fight for our lives”.

And so to the final concert, given by International Contemporary Ensemble and the Com Chor, and entitled ‘The Wide-Open Mouth’. Jessica Ekomane opened with nye, a work for solo electronics, the stage darkened, the audience in a muted blue light, as the speakers gave out the sounds of cicadas, chirrups, the sounds of night, joined by synth tones and swells in a slowly-repeating three-note melody, joined by dial-tone arpeggios and piercing high square waves.

Njabulo Phungula’s Playground Postcard offered a graphic score in which the musicians were invited to treat ‘playing’ as playground and sound as space, finding their own routes through its prompts. Fay Victor’s Overlap/Seam was likewise playful in its structure: music as game-like construction, a shared negotiation in which hierarchy is decentred an players must work together. Described in the programme as a ‘self-conduction’, it saw the performers pick pieces of paper from a bag handed out by Victor, then, throughout the piece, swap these around, the prompts creating a constant movement, a fragmenting texture efflorescing from the initial melodic seed laid by Finlayson’s trumpet melody.

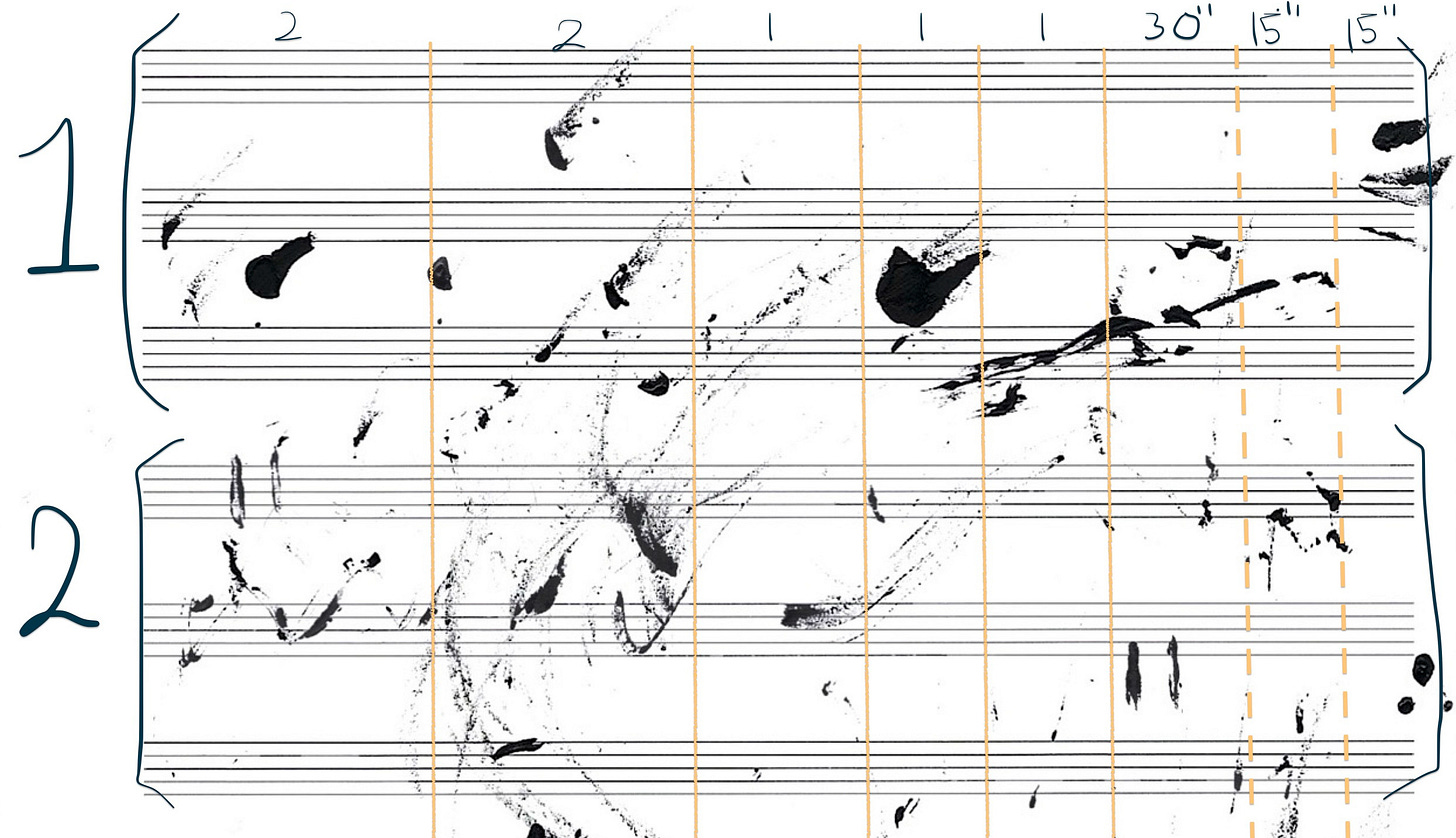

Elaine Mitchener’s th/e s/ou/nd be/t/ween offered a graphic score of a different kind (printed in the programme), ink smears and smudges on manuscript paper offering enigmatic spurs to self-organise sound. The quartet of Damian Norfleet, Fay Victor, Rebekah Heller and Joshua Rubin rendered it spiky and angular, with the moment-to-moment logics I tend to associate with improvisation balanced by the presence of recurring figures—in particular, a falsetto figure from Norfleet which sounded like a kind of avant-garde cuckoo clock—so that the piece seemed to move vertically as much as horizontally. The ten minutes flew by.

In two of the pieces, bloodcirclesairwhistles by Mitchener and Connections by Anthony R. Green, the choir swoop off the stage, up, down and around the large, sloping aisles of the vast hall, chattering, chanting, whispering, singing. In Mitchener’s piece, William Harvey’s 1648 text on the circulation of the blood by was transformed into a series of fragments, the constant circulation of the vocalists creating a different kind of surround sound” “blood, bl, bl, das Blut, circu, shh, shh”. Half-way through, the performers switched to sports whistles, their imperfect chirping drawing them back to the stage, a quiet electronic hum barely audible beneath it all, constancy beneath flow, constant flow.

Green’s Connections, meanwhile, touched on those experiences of isolation and connection—physical, emotional, erotic and otherwise—felt with particular keenness in the pandemic lockdowns of 2020. Green himself played melodica and piano (often at the same time), sang and recited a text, while choir and musicians flowed around, together and apart. It was as much cohesive as fragmentary, anarchically joyful as anxious, and it transformed the space: a vast movement, a parade. The weekend before, I saw the Sun Ra Arkestra move through the aisles in their time-honoured fashion at the Berlin Jazz Festival, and this felt like an extension. The parade says: we are here, we are not just on stage but among you, we are moving.

The event ended with Grain, Shelly Phillips leading the choir through a kind of live score projected from an onstage sheet of glass, on which she drew patterns in sand over a map of Africa, both triggering electronic reverberations and, seemingly, directing the music’s flow, as fortissimo falsetto shouts fading to piano figure s and harmonium drones before Phillips conducts the choir in a short final song: “here we are, / though even unto today you tear us apart”.

If Mitchener and Green set off movement, Phillips spoke about fixity: about standing ground, maintaining presence even in the face of dispersal. These are, perhaps, the two sides of the diaspora the festival as a whole sought to illuminate: the persistence of sound, the potentials it offers for survival, on the one hand, and its adaptations, its escapes, its flows forward into the future on the other.

As ever, this is about more than just music. As Harald Kisiedu noted in his talk, the first jazz programme in Germany was established during the Weimer Republic (at the Frankfurt Hochschule), and it was one of the first cultural institutions the Nazis closed down on assuming power. The fear of creolization, of Black and Jewish influences on German culture, lay behind the Nazi condemnation and persecution of ‘entartete Kunst’, ‘degenerate art’, influences already felt in the twin modernism of classical music: both the serialism of the Second Viennese School, whose principal architect, Arnold Schoenberg, was Jewish, and the jazz modernism of works like Ernst Krenek’s hugely popular opera Johnny Spielt Auf (Johnny Strikes Up). What both these trends are saying, Kisiedu noted, was that “the old world is finished”.

It’s at moment of real or imminent change that the forces of reaction most desperately rear their heads. On the second night of these events, Donald Trump was re-elected president of the United States by millions. As Kisiedu noted in his talk, in 1967, 70% of white Americans thought the pace of change of Civil Rights was too fast. Kisiedu drew links to Weimer Germany and to the rise of the Nazis, and the same day, news came out of a far right terror plot to establish a Nazi regime. Germany’s cultural institutions are hardly a bastion of free expression, as indicated in the last year’s barrage of anti-Palestinian censorship, and the matter of working with institutions—especially those funded by the State—will always be complex. (HKW was, after all, in its original guise as the Kongresshalle, a pet US Cold War project of Eleanor Dulles, sister of CIA Director Allen Dulles, which hosted events by CIA front organization the Congress on Cultural Freedom.)

But events like Always, already there nonetheless suggests a vision of that creolizing identity against which today’s fascists lash out, demanding the forced ‘acculturation’ of those who ‘refuse to integrate’ and threatening with deportation and ‘remigration’ those who don’t: as Lewis put it, “Afro-diasporic perspectives could lead to spiritual renewal in Europe to counteract the rise of Fascism in Europe and the US”. At the very least, as he put it in his onstage announcement during the penultimate concert, “it can no longer be said that there’s no such thing as an Afro-diasporic composer. We’re making you all into new experts in a new world”.