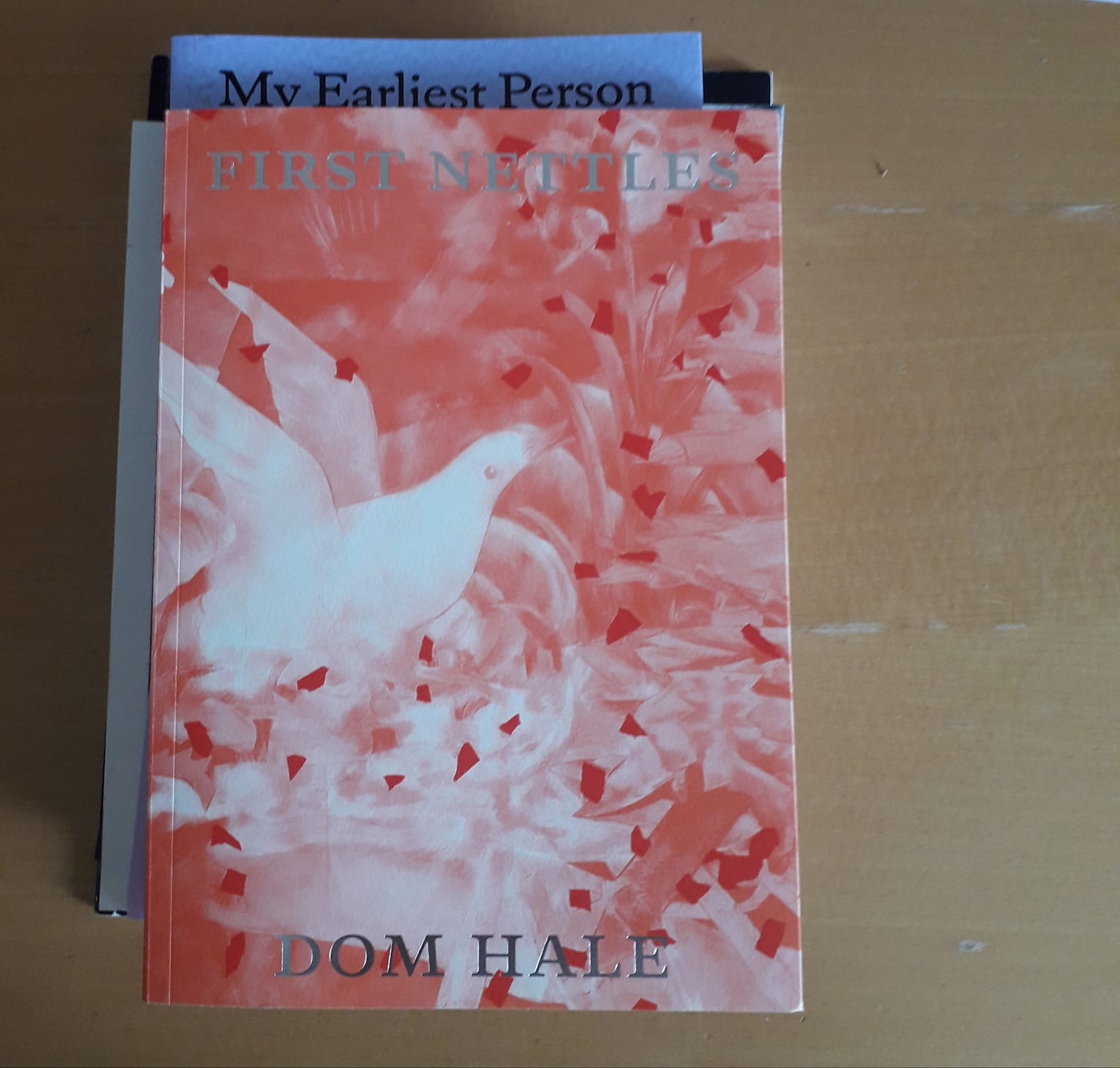

On the Substack version of this site, a review of Dom Hale’s First Nettles and Jennifer Soong’s My Earliest Person, both published by the Last Books. As it’s a long post (6,000 words or so) it’s only available in full behind the Substack paywall. But some excerpts below:

“How did the earlier poets hold it together[?]” asks Hale in the wracked ode ‘Castor and Pollux’, which I first read in a draft from 2021, just this side of the pandemic. “what defence does a poet have?” Not so much a defence of poetry or poetry as defence, but poetry as defencelessness. (“a poets lot is morbid frailty”...) The poem’s epigraph is from Stephen Jonas’s own resplendent ode ‘Love, The Poem, The Sea’—“I shall / with doubt / bloom in my season”. Jonas himself died young, that doubt overwhelming him—the earlier poets, too often, unable to hold it together—but Hale takes the message of loving survival in Jonas’ poem seriously. For, for all their faults, what are we writing poetry for if we can’t learn something from the poems that have gone before us?

“I found a pied wagtail and it spokes to me”, writes Hale in a parenthetical aside shot through with a deep Romanticism, as Romanticism emerged during the privatisation of the commons and the beginning of the Capitalocene. A poem takes or borrows its material from the world, but the way it does this is the opposite of the extractivist logic that governs that world system. A refusal to extract, is what a poem is, or could be.

In Soong’s poems, violence, forgiveness, love, exist beyond the theological register that still haunts the way we speak of them: “I say: what to do / with such forgiveness / of the unforeseeable?” Language betrays us: or we exceed it, it exceeds us. “we / leave behind what / we say we can’t”. “what is equal to more / than can be said”. To be equal to, to balance up, to come up with an equation that would solve things, would be one way: the well-made poem, rhyme as resolution, metre as an ordering of the normal disorder of speech. But poetry is not that. It overflows it, unbalances it: seeks instead, dialectically, to acknowledge imbalance and transformation. The poems move in the instability of that line break, that cut, as much as they move in the smoothing, soothing shell of enjambment, sound-pattern, echo. When our speech is choked off, we speak with stumbling fluency through that prohibition: it births our speech. We perform and refuse to move on and our desire is shared with others and others are internalised into us, this ensemble that is the poem. For

we get to where we can't, having been taught by the things in each other.Poems like Dom Hale’s and Jenn Soong’s sift through the grift, let it stick: not the fine details, but the jagged edges of feeling, which are a thousand small ridges, cuts, wounds, incisions on the break of a line, the placement of a comma, the absence of an apostrophe. Care in the scattering. [...] In our poems, our posts, our criticism: trying to find a form for these things we perhaps cannot even properly say to each other in conversation when we speak, these things we try to put our finger on, while the map moves beneath our pointing digits.

No comments:

Post a Comment