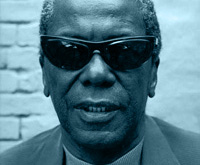

Sadly, April sees the passing of another great jazz musician; the pianist, composer, and bandleader Andrew Hill. He died from lung cancer on Friday 20th, just two months short of his 76th birthday. An important artist who held fast to his idiosyncratic vision, even when that meant long stretches in the commercial wilderness, his music experienced a resurgence in recent years through reissues and remarkable new projects. Where he once may have seemed a fascinating but marginal figure, his influence is now indelibly stamped on many of today’s most creative players.

Jason Moran, one of the most exciting young pianists of today, and a Hill protege, described his mentor as “The Man Who Knew More Than He Was Asked” - in other words, he knew more about different styles of music than people suspected. Hill famously carved out his own unique style of halting phrasings, odd chords and meters, and compositional left turns. His former student emphasized how Hill was also capable of pulling from a vast and surprising storehouse of styles at a moment’s notice. Moran noted how Hill was deeply informed by classical, funk, boogie woogie, cartoon music, and numerous other genres not normally associated with the maestro.

His 2002 big band album, 'A Beautiful Day' was part of a late-career resurgence, begun in 1999 with the critically-acclaimed 'Dusk', and continued until 2006's 'Timelines', reminiscent of his 1960s Blue Note Classics. The 2002 release represents Hill's strengths perfectly - a superb ear for texture and a clear sense of form welded to a freer, more open impulse that expresses itself in wild soloing; the perfect balance between tradition and innovation, composition and improvisation, intellectual weight and emotional power. Such traits can be found in the work Hill produced throughout his career, in particular the series of five albums he made for the Blue Note label in just 8 months in 1963 and 64, at the age of 32.

CAREER OVERVIEW

Hill was born in Chicago of Haitian parents in 1931, and raised in the heart of the city's black South Side. The great Earl “Fatha” Hines discovered Hill playing accordion and tap dancing around the neighborhood's nightclubs and theaters and became one of Hill’s considerable mentors. Another was Stan Kenton's arranger-trombonist Bill Russo, who introduced Hill to one of his greatest influences, the German composer and music theorist-in-exile, Paul Hindemith with whom Hill studies from 1950-52, and who would make a lasting impact on Hill’s intriguing compositional style.

Hill began gigging in 1952 and went on to play with Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dinah Washington and Coleman Hawkins. His first recording came in 1954, as a sideman for bassist David Shipp, and his first session as a leader came one year later, with the album So in Love for the Warwick Records label (accompanied by great Chicago bassist Malachi Favors). This was fairly conventional, and forgettable, hard bop, and Hill quickly forsook that sound, forming a pop-friendly big band known as the De'bonairs and playing as a reliable Chicago sideman before moving to New York in 1961 to play in the bands of Dinah Washington and Rahsaan Roland Kirk.

Always an avid disciple of bebop piano titan Bud Powell, Hill, like most jazz musicians of his generation, was shaken and reinvented by the radical music of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor in the late 1950s and early 1960s. His style beame a synthesis of Powell and Thelonious Monk's bop, Horace Silver's hard bop, and Taylor's dense avant-garde explorations, meshing those disparate sounds into something quite new and original, even iconoclastic: Hill, perhaps more than any other musician of his day, understood that one need not completely embrace the radicalism of the "New Thing" in order to develop the bop-rooted jazz traditions in those same directions. His was an advanced version of hard bop, one that was unafraid to incorporate the thick, dissonant chords and oblong modal work of Taylor and his contemporaries.

In 1963, he was contracted as a leader by Alfred Lyons, the founder of Blue Note Records who proclaimed him his "last great protege," and began one of the most consistently high-quality and forward-thinking recording streaks in jazz history with the November sessions that produced his album Black Fire. The streak continued the next month with Smoke Stack, then into the new year with Judgment!, Point of Departure, and Andrew!!!. On these records, Hill not only began broadening the harmonic canvas of jazz, but found his niche with the most advanced players of the era - peaking with Point of Departure, on which he led an ensemble featuring Joe Henderson, Eric Dolphy, Kenny Dorham, Richard Davis, and Tony Williams. If Horace Silver had represented Blue Note's hard-bop sound in the 1950s, Andrew Hill embodied the progressive Blue Note of the '60s, lending a vision of harmonically and melodically complex musical palettes to the label that now epitomizes jazz recording.

Unfortunately, Hill's tremendous contributions to jazz's artistic development in the 1960s were largely overlooked in the jazz universe (even by the many who bought Point of Departure). Undaunted, he built a cult following of jazzheads and critics, continued an exhaustive and exhausting run of performing and recording, and proceeded to write a new harmonic language and a new conception of time. His influence wasn't the explosive one of Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, or Miles Davis; rather, it was a slow seepage, as like-minded pianists (and other musicians) heard his unique stylistic approach, incorporated it into their own, then let other musicians do the same to them in a long chain of unknowing followers. Among his musical followers and sympathizers were Mal Waldron, Herbie Hancock, Muhal Richard Abrams, Don Pullen, Danilo Perez, and Jason Moran.

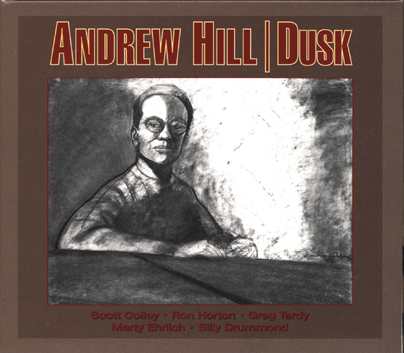

Though he continued playing and touring through the 70s and 80s, recordings as leader again for Blue Note in 1989 and '90, it took a new century for the bulk of the jazz world to finally catch onto, and marvel at, Hill's innovations; in 2001, when he released Dusk (Palmetto), he was raised up as though he were the newest and hippest sensation, not a 50-year journeyman and musical beacon. It won Album of the year in both major jazz publications, Down Beat and JazzTimes. Two years later, Hill won the Jazzpar, the Danish award that is perhaps the most selective and prestigious in the international jazz community.

By 2006, after touring America and the world and returning to Blue Note Records for the release of the Time Lines album, he had four times been named by the Jazz Journalists Association as Jazz Composer of the Year; been one of the earliest recipients of a Doris Duke Foundation Award for Jazz Composers; won a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Jazz Foundation of America; and had Time Lines, his last recording, once again named Jazz Album of the Year by Down Beat, the New York Times, and numerous other publications and critics.

Hill learned in 2004 that he had lung cancer; fighting it every step of the way, he continued to create vital forward-charging music, causing NPR to note that "Hill still creates music as if his best work is ahead of him." He played his last live date in New York City on March 29, 2007, and less than two weeks later, the prestigious Berklee College of Music announced that it would award Hill an honorary doctorate in music at its May 12 commencement ceremony. Sadly, Hill would survive for only nine days after that announcement.

A MUSICAL TOUR THROUGH ANDREW HILL'S CAREER

Here's some commentary on a few career highlights, and, to accompany them, here are the tracks themselves -

http://rapidshare.com/files/28474251/Hill_Career_Overview.rar.html

(4) COMPULSION - (1965, Blue Note) TRACKS -- Compulsion/Premonition

'Compulsion', from 1965, has just been re-released by Blue Note, and it's about time: one of his freest, more 'out there' sessions, it contains plenty of intriguing compositional and improvisational ideas and textures, and has a stellar line-up of Freddie Hubbard, John Coltrane-influence and Sun Ra-accolyte John Gilmoe, bassists Cecil McBee and Richard Davis and drummer Joe Chambers, as well as Nadi Qamar on percussion and Renaud Simmons on congas.

First up is the 14-minute title track, which contrains a 4-minute section that the free-jazz blog 'Destination...Out' describes as "simply the most thrilling four minutes of Andrew Hill’s entire illustrious career." (You can find their blog, and Hill tribute post, at http://destination-out.com - I hope they won't mind me quoting from their excellent commentary on these two tracks).

...the section begins at the 3 minute mark, when Hill’s piano reenters the tune and the dark rhumba groove begins. That stuttering Latin feel subtly underpins this entire section, allowing Hill and trumpeter Freddie Hubbard to become increasingly unhinged. Hubbard soars against the beat with an impassioned solo that’s full of rhythmic stabs and melodic shrapnel, displaying his often-underappreciated avant-garde credentials. Hill slowly turns up the heat on everyone, almost subliminally at first until he begins to unleash a tidal swell of notes. This oceanic rumble is so physical and menacing at first it’s hard to believe it’s coming from him. It’s as if a whirlpool has suddenly emerged at the middle of the tune, threatening to capsize the other players and suck them into its vortex. Hill plays as if he’s limning the void, gleefully. Amazingly, the song doesn’t get blown apart, but manages to stay afloat and even on course –– but just barely. It’s a remarkable passage –– the musical equivalent of watching an ocean linear tossed aloft by 100-foot waves.And there's still 10 more minutes after that, including a a frenzied full-band coda. Hopefully you'll agree that there's a lot to listen to here - as rewarding an experience as any Hill created. With Freddie Hubbard in trumpet, John Gilmore on tenor sax and bass clarinet, Cecil McBee on bass, Joe Chambers drums, Nadi Qamar percussion and Renaud Simmons congas, this is 'Compulsion'.

The second selection, 'Premonition, dials down the drama with a moody and atmospheric feel that perfectly suits the title, and perfectly highlights the open-endedness of Hill’s approach. Possibly, this is one of the reasons he remained something of an elusive figure throughout his career - there's something unsettlingly unresolved in his compositions; they have the feel of a question more than an answer. The track also has a wider significance beyond the immediate context of Hill's style, as the D:O writers again so accuarely put it,

capturing a lot of what was great about the so-called 'New Thing' of the 1960s: the softening of a strict theme-solos-theme format; a willingness to play with texture, unconventional instrumentation, or odd pairings (with some players dropping out for a stretch); side-by-side soloing (trumpet vs. bass vs. bass, for example); and a more elastic sense of time.All this comes with some retention of structure and solidity, and a sense of sheer beauty that eclipses all the other factors in importance and makes this a superb track.

(5) INVOLUTION (rec. 1966/7, rel. 1975, Blue Note) -- TRACK - 'Violence'

Although recorded in 1966 and 1967, it took almost ten years for this collaboration between Hill and Sam Rivers (pictured) to see the light of day as part of a two-record set. It's Hill, Rivers (sax), Walter Booker (bass), and J.C.Moses.on this alternate take, notable for a freer, looser feel that sees Rivers' playing tethered to emotion, while never losing coherence or technique, with Hill providing a slightly more detached, though extremely dramatic, and by no means unemotional approach.

(6) BUT NOT FAREWELL (Blue Note, 1990) -- TRACK - Westbury

Skipping forward a few years now (my reccomendation for Hill's 70s work would probably be 'Lift Every Voice', which comes compelte with gospel choir - while a bit corny, some moments, like 'Hey Hey', are undeniably effective. Carlos Garnett provides some nice tenor stylings). In 1989, Hill had re-signed with Blue Note, and recorded 'Eternal Spirit', which he followed in 1990 wiht 'But Not Farewell'. Featuring Greg Osby on lilting soprano sax, I've picked a gorgeously nostalgic and wistful track called 'Westbury', showcasing a more straightfowardly emotional side to Hill than might have been apparent from the earlier tracks.

(7) DUSK (Blue Note, 2000) -- TRACK - Ball Square

Hill went fairly quiet for the best part of a decade after those two albums, described by critics as his '2nd Blue Note period', but in 2000 he made a triumphant return with a sextet recording called 'Dusk', released on the Palmetto label, which was voted best album of the year by both DownBeat and Jazz Times, and led to a new spurt of creative activity and recording. The track selected is a playful number called 'Ball Square', with the sextet of Ron Horton on trumpet, Greg Tardy and Marty Ehrlich on saxophones, Scott Colley on bass, and Billy Drummond on drums.

(8) A BEAUTIFUL DAY (2002) -- TRACK - New Pinnocchio

After the success of 'Dusk', Hill sprung something of a surprise in 2002, with a live big-band recording. In a way, though, it shouldn't be seen as two much of a departure - Hill's studies with Hindemith and compositions throughout his career revealed a musician who possessed a writing ability far above that of most jazz musicians. The album, 'A Beautiful Day', featured the band performing eight original compositions at New York's legendary Birdland club. Alternately, and sometimes simulatenously energetic, moody, stark, elegant and poignant, it contains what I think is some of the best music he ever produced, a success that was continued when an expanded version of this line-up, featuring a number of British stars, performed a triumphant set at the Bath Jazz Festival in 2003. The musicians on this track are saxophonists Marty Ehrlich (a veteran "downtowner" and musical associate of Muhal Richard Abrams, Julius Hemphill, Wayne Horvitz and John Zorn) and Greg Tardy (Hill’s label mate who is much-in-demand as a tenor soloist); trumpeter Ron Horton (a stalwart of the Jazz Composer's Alliance); bassist Scott Colley and drummer Nasheet Waits. Joining this group are John Savage, Aaron Stewart and JD Parran on saxophones,Dave Ballou, Laurie Frink and Bruce Staelens on trumpets, Charley Gordon, Joe Fiedler and Mike Fahn on trombones, and Jose Davilla on tuba.

(9) TIMELINES (2006) -- TRACK - Timelines

In 2006, Hill made what would turn out to be his final recording for Blue Note, and one that some see as up there with his 60s output. It features trumpeter Charles Tolliver, himself an underrated master, who had earlier played on Hill's Dance With Death and co-led a storming big band with Stanley Cowell called 'Music Inc', who I've played on this show before. 1970. Joining Tolliver and Hill on Time Lines are three younger musicians well established on the New York scene: Gregory Tardy on reeds, John Hebert on bass and Eric McPherson on drums. In an interview, Hill praised their ability to play “three or four different ways. Whenever you hit a musical mood, hey can enter it.” He also cast doubt on the alleged creativity deficit among younger players: “I hear about everything that they’re not. Very few people talk about everything they are. There are so many flowers on the scene, it’s utterly amazing.”

Listening to Time Lines, there’s no mistaking hat Nat Hentoff, in the liner notes to Shades (1986), meant by “the time-within-time-within-time of Andrew Hill.” Richard Cook and Brian Morton, discussing Hill’s earlier work in The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, refer to tempos that are “too subliminal to be strictly counted,” harmonic language “that isn’t so much minor-key as surpassingly ambiguous….” These elements are present on Time Lines, although the tone colors of the title track are disarmingly bright. Tardy festoons the album with ravishing clarinet and bass clarinet. The piano sound is vast. “I’ve made it a project to figure out how to record the piano,” Hill commented. “The key is not to approach it as an accompanying instrument. Instead of instruments accompanying each other, have equal volume on all, so they all can stand on their own. Otherwise it throws off the quality of the performance.”

As critic David R. Adler Notes, a “stammering” motif occassionaly surfaces in Hill's work, and you can hear that in the main melody of this track. Whether a conscious or unconscious impulse, it's one that underscores the genuine and searingly individual quality of Hill’s output. His art may be a perpetual work in progress, premised on instability and a willingness to experiment in public, but Hill is always after something specific: “These magic moments,” he says, “when the rhythms and harmonies extend themselves and jell together and the people become another instrument. These are things that are priceless and can’t be learned; they can only be felt.”

(10) TRINITY STREET CHURCH, March 29 2007 (FINAL PERFORMANCE)

Video at http://trinitywallstreet.org/calendar/index.php?event_id=39988#

Hill's most famous work is 'Point of Departure'. And I think that title perfectly sums up the impulse that he represented, and that lies behind so much great jazz, and music from all genres - the ability and willingness to push boundaries, to head out for the unknown, to buy a "ticket to nowhere" as Wayne Shorter puts it, creating work that's based on the knowledge and forms of the past but has the vitality and freshness of the future.

All this was present in his last performance, at Trinity Church in New York, from March 29th this year. A recording session had been scheduled by Blue Note for April 18th, but sadly Hill was unable to make it, and so this presumably constitues his final performance, or at least his final recorded performance. As can be seen from the video of the concert, Hill is clearly frail, his hands shaking as he moves them over the piano, his grey suit hanging off his bony arms, and the music is perhaps not as assured as in his heyday, but enough of his personality comes through to warrant me playing this. In a sleevenote from the late 60s, Hill seemed to regret the fact that he was regarded solely as an intellectual, abstract musician, when he valued the more rootsy R&B and Soul/Gospel influenced jazz that was also a part of the blue note label (He wrote "Rumproller" and was proud of the fact). I think that balance between serious, intellectual, somewhat avant-garde musicianship and a more grounded, earthy feel comes across here - the music has a sort of solemn, understated eloquence that perfectly suits the church surroundings in which it was recorded, yet with tangy traces of jazz modernism that, far from clashing with the more traditional aspects, make them even more rewarding. Take a look at the video - the Andrew Hill trio, with Hill on piano, John Herbert on bass and Eric McPherson on drums, recorded at Trinity Church in New York on March 29 2007, with a liturgically-based composition called "Before I..." Rest in peace.

EARLY SIDEMAN TRACKS

And, as a bonus, here are some rare early tracks featuring Hill as a sideman: first, on a few 45 RPM singles recorded under the leadership of bassist David Shipp; then, at a concert given at St Louis, Missouri in 1961 (as this is ripped from a bootleg LP, we can't be exactly sure about the details, but it was probably originally a radio broadcast); and finally, the title track from a little-known 1963 album by the strikingly original alto saxophonist Jimmy Woods called 'Conflict'. Full discographical details for all these early tracks (and, indeed, all of Hill's recordings) should be easily available at the superb Jazz Discography page at jazzdisco.org.

http://rapidshare.com/files/28473669/Early_Sideman_Tracks.rar.html

And make sure to visit andrewhilljazz.com, where you can download MP3s of a solo performance Hill gave at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London.