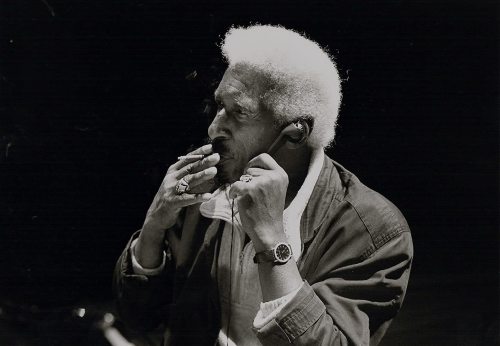

[100] Ganja and Hess (1973, dir. Bill Gunn)

Manthia Diawara posits Melvin Van Peebles’s ‘Sweet Sweetback’ and Bill Gunn’s ‘Ganja and Hess’ as emblems of the two trajectories of U.S. Black Film in the 1970s: ‘Sweetback’ as Wright’s ‘Native Son’, ‘Ganja’ as Ellison’s ‘Invisible Man’. If ‘Sweetback’s genre approach channelled certain icons of rebellion—albeit along strongly masculinised and easily-commodified lines—‘Ganja’ represents a far more elliptical and experimental approach that uses the ostensible framework of genre cinema (the vampire movie) to probe anxieties, to present crises from multiple perspectives rather than resolving them through masculinised identification, and to maintain open form as a key principal of what might Black cinema might be. Butchered, re-edited and variously mangled over the years, it’s now possible to watch both Gunn’s intended version in all its avant-garde fascination and to compare the expository scenes shot but then removed from the final cut, only to be restored for the re-cut exploitation-movie version retitled ‘Blood Couple’. Watching these scenes only serves to emphasize just how strange and dream-like Gunn’s editing renders the final product: almost every deleted scene provides a piece of plot information that would contextualise and make narrative sense of the scenes we see in the final version as floating fragments, disconnected and elliptical fragments heavy with a symbolism that won’t fully reveal itself. The film indexes class tensions—Ganja marries up for financial security, has bourgeois pretensions, delights in lording it over a servant—while Hess sequesters himself away from society as such in a quasi-aristocratic mansion (the equivalent to Dracula’s castle), feeding on sex workers and intern/assistants, his class position as an academic anthropologist connecting both to occulted knowledges connected to African survivals—the remixed chants and flashbacks of ghostly African figures associated with the moments of possession and blood lust that constitute his vampirism—to a class parasitism that’s also ambiguously positioned in relation to myths of African savagery and their Afrocentric challenge (or reclamation). Drug addiction forms another layer in these swarms of symbolic parallel, along with the collective ecstasy of the church, depicted in an astonishing, documentary-style sequence that Spike Lee’s staged re-enactment for the mediocre remake, ‘Da Sweet Blood of Jesus’, comes nowhere close to matching. Ultimately, Ganja achieves an ambiguous independence, the men in her life both finding it impossible to reconcile themselves to the contradictions they live through: Hess’s climactic, guilt-ridden repentance and self-annihilation through subjecting himself to the shadow of the cross form a parallel to the earlier suicidal ideation of Ganja’s estranged husband (Gunn himself) for whom the demands of art and the torments of racial expectation form a deadly cocktail, while Ganja herself chooses to live as a vampire, eyeing the naked young man who dashes in slow motion over Hess’s corpse and then facing the camera in a series of jump-cut shots in which her facial expressions seem to freeze, then compose themselves, ending in an ambiguous smile that seems at once intensely melancholic and imbued with a conspiratorial satisfaction: power at what cost? In a society predicated on vampiric economic forms, entangled in the social processes of gendering and racialisation, along with projections and imaginations of historical origin (the African past), this conclusion comes to seem both a kind of victory and the ultimate capitulation. Gunn won’t let us read it any one way, and the film remains exceptionally rich: a reinvention of the vampire film—of the horror film per se—as a key work of Black American experimental cinema; as a meditation on desire, art, power and exploitation; as a beautiful and frightening fever dream as Ellison’s invisible man in his basement, and in many ways stranger.

99) Losing Ground (1982, dir. Kathleen Collins)

‘Losing Ground’ highlights gender and racialisation whilst refusing to be a message movie, according its subjects the same reflective possibilities the familiar white bourgeoisie of Euro-American art cinema. Shot in burnished colour, Collins’ film is visually stylish without being either tragic or comforting, to catch the ebb and flow of conversation without being tied to realism. Married to a philandering painter (Bill Gunn), Sara Rogers (Seret Scott) is a philosophy professor whose dedication to the life of the mind—both hard-won in terms of both gender and race, and a kind of protective screen against the vulnerability to which she might otherwise be subjected—comes up against the suggestion of alternative experience through her research into ecstatic experience and her attraction to the older movie star (Duane Jones), with whom she’s starring in an experimental short film. (Gunn and Jones—the latter most famous for ‘Night of the Living Dead’, the former a maverick and mistreated director—both memorably appear in Gunn’s own ‘Ganja and Hess’, and their presence is an important part of the film.) The competing—or apparently competing—tendencies Rogers perceives in herself come to be partially figured through the abstracted narratives of the short film itself, a take on the ‘tragic mulatta’ narrative (via an allusion to ‘The Scar of Shame’) which at once reinforces the connection of death, forbidden desire, and racial stereotype, and, in its production, suggests ways of integrating art, the sensual and the intellectual that Rogers has previously denied herself. Meanwhile, affected by Victor’s latest affair, Rogers feels herself unmoored—losing ground, as the film’s title has it—in a manner that at once suggests possibilities and the shaky walkway on which she’s constructed her way of being in the world. The film ends in a kind of parody of resolution—the fatal shooting that ends the short film observed by Victor as Sara breaks down, the boundaries of performance, identification and control breaking down. This is not a film that tries to tie up its loose ends or resolve its dilemmas, and all the better for it.

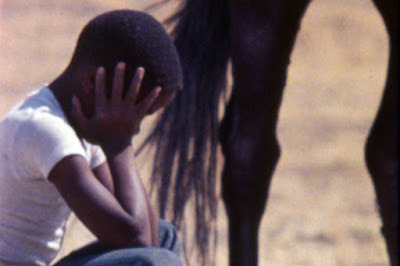

[98] Nothing But a Man (1964, dir. Michael Roemer)

Ivan Dixon plays the good-hearted but troubled railroad worker who falls for, and marries, the preacher’s daughter, their attempts to build a life disrupted by his failure to hold down a job—effectively blacklisted when he starts attempting to organise his fellow workers—and the tensions of class differentials and the climate of racist surveillance and gendered expectations. Dixon’s wife is played by Abbey Lincoln, then in the process of challenging the images for which she was being prepared—the chanteuse-siren or the tragic jazz singer—having been involved in political activism and recorded some of the most important political jazz albums of the decade. Here, her performance is unaffected, subtle and moving. Dixon and Lincoln reconcile by the film’s end, though whether or not they’ll make it is open to question, and his lashing out in an incident of domestic violence offers a disturbing shift in register that can’t be driven from memory by the ostensibly ‘happy ending’. Throughout, the film doesn’t romanticise, editorialise, or patronize—quite remarkable, given its white directors—and, as such, it stands as one of the finest early examples of what—with some qualifications—we might call ‘Black Cinema’. (David C. Wall and Michael T. Martin provide a useful consideration in their essay ‘Nothing But a Man and the Question of Black Film’). This is a film that displays love and intimacy in ways that go well beyond cliché, yet which refuses to reassure. No wonder Malcolm X was a fan.

[97] Emma Mae (1976, dir. Jamaa Fanaka)

Jamaa Fanaka would soon take the L.A. rebellion down the blaxploitation road others rejected—‘Welcome Home Brother Charles’ as perhaps the most extreme depiction of the myth of black male hyper-sexuality seen in film, whether as intentional or unintentional satire—but ‘Emma Mae’ is a subtle and personable film that eludes any of the generic categories placed on it in its marketing (the re-edited version as ‘Black Sister’s Revenge’ is a particularly egregious case). Its titular heroine comes to the big city as a naïve ‘country girl’, falls in with a drug dealer who goes to prison after resisting the cops, goes on the run herself, starts schemes to get him out of jail—schemes that appear to borrow from genre pictures (the car-wash from the teen movie and the bank robbery from the heist movie)—and finally leaves him after he reveals himself to be the cheating egotist we’ve always suspected him to be upon release. The plot can be somewhat wobbly—particularly given those generic lurches, and characters who never quite seem fully integrated, like the elder Black Nationalist who serves as mentor to this group of teenagers for reasons that are never quite clear—and for what is a conventional narrative film, it can occasionally become derailed or unstuck. Yet, in the main, it successfully negotiates the traps of stereotype—imbricated as they are with the pressures of genre film-making and the exploitation of suddenly marketable modes of Black identity. Above all, it’s distinguished above all by the performance of these actors, none of whom are well-known, and its sympathetic portrayal of Emma Mae herself—at once naïve and nobody’s fool, a refreshing depiction of a protagonist who is neither idealised nor demonised, and who ultimately comes through accepted as part of a group yet refusing to compromise herself.

[96] Portrait of Jason (1967, dir. Shirley Clarke)

Shirley Clarke’s entire cinematic output engages with displacements of otherness—as a rare female filmmaker in an intensely masculine world, as Jewish, as a bohemian, she chose to depict another marginalised community—that of Black life in New York in ways that identify and displace in troubling fashion. Clarke’s films were undoubtedly pioneering in terms of both form and subject matter. While ‘The Cool World’ attempted to marry its documentary strands with more conventional bounds of the melodrama, to mixed success, the more experimental ‘The Connection’ had more explicitly engaged with the strained relation between the bohemian filmmaker and the Black working class subjects they depicted and exploited (in the case of that film, jazz musicians waiting for a fix). ‘Portrait of Jason’ goes further yet, both in its status as documentary—the camera rolls on its subject, the queer performer Jason Holliday as he’s interviewed off-camera by Clarke and her (Black) partner Carl Lee—and the uncomfortable exposeé both of its subject’s and its own motivations. Holliday is a hustler, a performer—these are modes of survival. Clarke’s and Lee’s demands that he ‘tell the truth’ and ‘reveal himself’—that he perform the role of the tragic or manipulative gay man—try to break down the very performance they encourage. Holliday, of course, understand that it’s all performance—as when he performs the role of the subservient servant to his white employees, or hustles for drinks and love, he can’t afford to let the mask slip. Drunken vulnerability, tears and apologies are thus their own performances. Clarke demands that Holliday suffer, then tells him that he’s not suffering. More tears, more stories: “what else ya got?” Holliday is celebrated as trickster, as purveyor of cool, as exotic sexual deviant, yet his sexuality is threatening to Lee, his race an object of complex curiosity to Clarke: both of them appear to find Holliday threatening and fascinating in equal measure, and the images we see on screen appear to wrestle with this sense of disgust and love (a love which Clarke says only came through in the editing, the filmmaking at the time approaching an act of revenge for things Holliday had done, or was perceived to have done to hurt her and Lee). The film comes to seem like a struggle between Holliday—on-screen—and Clarke and Lee—off-screen. It’s unclear, by the end, how the power relations have shifted, who has ‘won’, what we’ve learned. Is Holliday’s image his own, or has it been stolen by Clarke? Has he turned the tables or is he defeated and exposed? Rarely is the struggle for authorship of a film laid bare. But then again, rarely are films—‘documentary’ or otherwise—so stripped-down in their conception and execution: every frame contested, raw and troubling.

[95] Not Reconciled; or, Only Violence Helps Where Violence Rules (Straub-Huillet, 1965)

A miracle of editing, this trumps Resnais’ ‘Muriel’ for the speed and concision of its shot sequences, turning a reasonably straightforward, if sprawling story of three generations of a German family during the two world wars into a labyrinth of detail, equivalence and juxtaposition that demands total attention from its audience at every moment. As well as making its point about the recurrences of history, and, above all, the return of Fascist politics under gentler guises made in more condensed form in ‘Machorka-Muff’, this model of the engaged spectator will form the basis for the recitations and tableaux of their subsequent career. Both elements–the extreme speed of editing and the reduction of ‘cinematic’ technique (editing, camera movement, and so on)–are not so much opposites as different ways of modelling such attention and reflecting on historical equivalences and gaps, often through the prism of literary texts (here, as in ‘Machorka’, a work by a Heinrich Boll). These two early films further suggest that political rage and analytical clarity are by no means opposite forces, as they’re so often portrayed. As the film’s title suggests, reason and human dignity are on the side of the elderly woman who tries to shoot a politician, rather than on any gestures of placatory moderation and reconciliation, and this refusal of reconciliation happens on the level of cinematic form as well as narrative. Still challenging and vital.

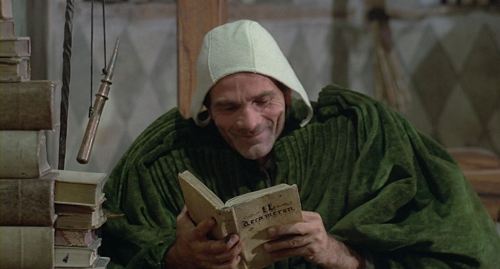

[94] Machorka-Muff (1963, dir. Straub-Huillet)

Very early Straub-Huillet, still within the bounds of the fiction film, with an incisive, bitterly satirical portrait of a former Nazi officer inaugurating a military memorial that will rehabilitate his former superior and open a new military academy in its grand tradition. Close-ups of the newspaper he reads at a cafe lay out the context of re-militarisation in Adenauer’s West Germany–dream sequences in which the officer appears to unveil numerous copies of himself attest to his egomania, perfectly of a piece with the masculinist, nationalist cult that barely even attempts to hide its continuities with Nazism. Machorka-Muff is also a self-confident philanderer, moving on to his sixth marriage–an aristocratic match–and admiring himself in the mirror with narcissistic delight. ‘An abstract visual dream, not a story’, proclaims the preface, and the fetishistic attention to detail that characterises both Muff’s military ‘propriety’ and the way that the screen is split into precisely co-ordinated fragments of the larger whole anticipate the intensely swift editing of ‘Not Reconciled’ at a slower pace. As effective a warning against the after-effects of Fascism as any. ‘Will the public swallow it?’ wonders an interlocutor about the unveiling. The answer is instant and absolutely self-confident. ‘The public swallows everything’. The film challenges its audience to prove otherwise.

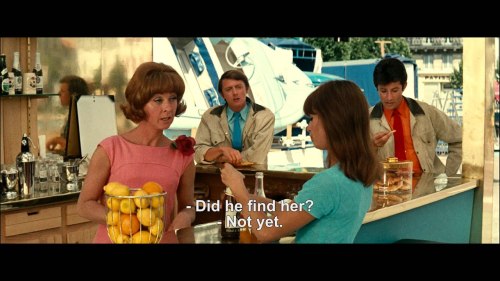

[93] Prima della Rivoluzione / Before the Revolution (1964, dir. Bernardo Bertolucci)

Bertolucci’s psycho-sexual obsessions have always seemed a strange fit with his concern with revolutionary politics: the one transplanted onto the other, but the two so imbricated within the films themselves that the substance beneath the undeniable style can be hard to discern. Here, it’s incest–apparently as reaction to a homoerotically-tinged friendship with a young Communist–that provides an outlet for the self-hating young bourgeoisie who ultimately settles for his position in society, marrying his normative girlfriend and taking the career path expected of him. If Pasolini–for all the faults in his exploitative relationship to the young men of the subproletariat–has come, by ‘Salo’ at the very least, to articulate a theory of the interactions between sexuality, consumerism and the shifting mores of Italian society, one that can take account of the defeat, through incorporation, of the sexual revolution, Bertolucci’s obsessions are both more ‘accessibly’ filmed and less articulate. Bertolucci’s preoccupation with homosexuality–which he seems to regard with both openness and fascinated horror, thus here places left-wing political comradeship and homoerotic attraction as something like equivalents, yet in the later ‘ll Conformista’, he implies that such attraction is also in some ways tied to sadistic Fascist constructions of masculinity. Might the disillusioned bourgeois of ‘Before the Revolution’ have become the complicit conformist of the later film? We might well entertain the possibility. As it stands, the film is somewhere between an incisive self-critique of the bourgeoisie and a confused projection of sex onto politics that provides analysis neither of the politics of sex nor the sex of politics.

[92] Vitalina Varela (2019, dir. Pedro Costa)

Costa moves from the implications of elements of his previous films—the stories told by Vitalina Varela, first presented as a kind of cameo in ‘Horse Money’—as part of a kind of daisy chain link, a gauzy web of connections etched in shadow, the vagaries of memory, the whispered incantations of repeated tales, which makes viewing the films, as each new work supplements, perhaps even contradicts the last, impossible not to project back on the former in the light of the latter. Abandoned by her husband in Cape Verda, Vitalina comes to Lisbon for his funeral—which she missed by several days—and resolves to stay in his shack as a virtual recluse. The film once more concentrates on loss—the failure of a love relationship—and the fractured interactions that constitute the social environment in which the one left alone finds themselves, yet, once more, these are to an extent mitigated by acts of communal support. Yet Vitalina’s gendered critique—directed to a priest played, once more by Ventura—suggests that such support may benefit from patriarchal networks (as ‘papa’, after all, Ventura incarnates the patriarch). Vitalina condemns the priest played by Ventura for the pity he dispenses to the husband who abandoned her in Cape Verde, and who died alone in Lisbon: “Men favour men. When you see a woman’s face in the coffin, you can’t imagine her suffering.” Costa notes that, in real life, when Vitalina first came to Lisbon after he husband’s death, she was left alone in her deceased husband’s shack for days. ‘Vitalina’ closes with a flashback: Joaquim and Vitalina building their house together in Cape Verde, before Joaquim left for Portugal. ‘Vitalina’ is a film which has so often been about close-ups of faces and cramped spaces, yet Costa sets up this shot, a moment of intimacy which might traditionally be shot with a closer focus from a distance. Viewed from longshot, we cannot hear and can barely see the couple’s interaction. We might note here Vitalina’s gendered labour—carrying a brick on her head up to the roof where her bricklayer husband applies the cement—and her gesture of affection—putting her arm around Joaquim—which appears to be rebuffed, as she goes and stands on the far side of the roof, looking out to sea (Costa has described the Cape Verdean women left behind as ‘sentinels’). At the same time, one could read the Cape Verde flashback in combination with the moment when Joaquim’s friends visit Vitalina, coming together to fix the leaking roof of the shack. Even if all these relations tend to fall apart, they are at least attempts at working together to ease poverty and loneliness. One of Joaquin’s friends recalls their meeting in prison, the development of their connection: yes, we’re all shits and we cheat and lie, both to others and each other, but we also look out for each other. As in ‘Colossal Youth’ and ‘Horse Money’, this open ending can be either as affirmations of hope and possibility—from the darkness to the light, literally in the case of ‘Vitalina,’ which moves from the shadowy world of present-day Lisbon to a sun-lit flashback to her Cape Verdean past—or reaffirmations of existential misery. Rather, like the ‘sentinel’, these films pay witness and keep watch.

[91] Cavalo Dinheiro / Horse Money (2014, dir. Pedro Costa)

It’s impossible not to read Costa’s Fontainhas films in dialogue: to see ‘Colossal Youth’ without then seeing how its concerns morphs into ‘Horse Money’ and ‘Vitalina Varela’. Both taken together and separately, and in large part through their intensely collaborative nature, Costa’s films create a community that acknowledges, rather than attempting to suppress, fracture, loss and separation. The community of Cape Verdean migrants are subject to workplace accident, suicide, the pain and indifference of hospitals and welfare offices and other bureaucratic spaces which promise only mere survival, often accompanied with the threat of punitive discrimination, surveillance, exclusion and deportation; it’s this background that takes centre stage in ‘Horse Money’. The performers here tell both their own stories and those of others, and in which events are re-staged, either verbally or in ghostly, symbolised recreation, in ways that render them more, rather than less, ambiguous. This is a film about loss: a loss might equally be tied to the breakdown of domestic relationships, the ravages of addiction and poverty, or the political circumstances of a coup d’etat, of metropolitan racism, or the failure of decolonial revolution. ‘Horse Money’ seems to suggest this as something approaching existential condition: visiting Ventura in a hospital, a compatriot opines: “We’ll keep on falling from the third floor. We’ll keep on being severed by the machines. Our head and lungs will still hurt the same … We’ll be burned … We’ll go crazy … We always lived and died this way … This is our sickness.” Yet this class-specific experience is linked to specific, if haunted, spaces associated with the repressive or ‘benevolent’ aspects of State power—hospitals, prisons, offices (in which a worker might symbolically wait for their salary for 20 years), factories in which a worker’s guts are spilled by machines, documents which grant the bearer the rights of protection and subsistence and are constantly shuffled, displayed, inspected, held to under the surveillance and monitoring of the state. Stuck in the elevator, endlessly between floors, or the subterranean corridors of a building that’s at once hospital, prison and asylum, the film takes place in an endless nocturnal limbo. Yet, even within this nightmare world, there are also moments collective care than those of the State’s bureaucratic apparatus, the classist and racist indifference that extends or withholds housing, food, money to the bare minimum, that replaces outright racist hostility and violence with slow, rather than fast death. Costa describes his film as acts of ‘revenge’ against the Portugese state on the behalf of immigrant populations who are ‘doomed’ from the moment they set foot on a plane. But whose revenge? And what is the relation of revenge to hope? As the film ends, Ventura leaves the hospital: the camera lingers on a set of knives in a window, harking back to his story of injury in a knife fight. Tool of self-defense, index of trauma, or symbolic fight in the war of the oppressed? Perhaps all three.

[90] Juventude Em Marcha [Lit. ‘Youth on the March’] / Colossal Youth (2006, dir. Pedro Costa)

The English language title to the film does not provide a literal equivalent to the Portugese original–’Juventude Em Marcha’–a decision that apparently originates with its director, who likewise translates ‘Cavalo Dineiro’ as ‘Horse Money’ (rather than the more literal alternatives such as ‘A Horse Named Money’). While the English title emphasizes scale, a cultural reference point beyond the specific locus of the Cape Verdean immigrant community on which it focuses, and thus a point of access for European audiences mystified by this underrepresented world, the Portugese has a specific valence it’s useful to consider: a revolutionary slogan from the Cape Verdean independence movement, it renders youth as mass or class rather than the English language suggestion of youth as property or thing, designated by adjective rather than verb, suggesting something static (a statue, a colossus) rather than action, activity, movement. As such, it loses the contrast, central to this and to Costa’s other Fontainhas films, between the revolutionary hopes associated with youth and with decolonisation as they fade with time, with ageing, with loss of various kinds, with the effects of workplace discrimination, industrial accident, drug use, housing precarity, the failure of the metropole or the colony to usher in the new era promised by the end of Fascist dictatorship and its rule at home and abroad. Movements or moments that might have seemed at the centre of things—the decolonising moment’s contribution to changing the course of world history, the beginning of a new life for Cape Verdean migrants to Lisbon (Costa likens them to ‘pioneers’)—retreat once more to the condition of the marginal, the marginalised, the cast-off and discarded, to conditions of loss both metaphorical and literal: the Fontainhas neighborhood literally razed as the film was shot; or performers from previous films who had died by the time the next film was to be made. In ‘Colossal Youth’, we follow Ventura—a Cape Verdean migrant labourer whose arrival in Madrid coincided with the racist gangs whose targeting of migrants rendered the Carnation Revolution a very difference experience to that of middle-class whites such as Costa. In recreations of those moments—though they’re not immediately identified or obvious as such—Ventura and his friend Lento sit in the protective shack they’ve built, listening on a scratchy portable turntable, to Cape Verdean band Os Tubarões’ song ‘Labanta Braço’, a jubilatory celebration of independence in Cape Verdean creole which urges its listeners “Grita, viva Cabral” (‘Let’s cry out, Viva Cabral’). (Ventura will later sing this song, a capella, at a dinner with one of his ‘daughters’, having told the story of how he met his wife, finally seducing after he mocked her singing at a Cape Verdean independence celebration and she playfully hit him over the head with a flagpole.) The first time we hear the song, lines skip and repeat as Lento compulsively scratches the table on which the turntable has been placed with a pen, before Ventura gently stills his hand, holding it in a gesture of pacification and comradely friendship—later repeated when he holds hands with present-day Lento in a burned-out apartment and recalls the great fear of death they both had in the 1970s, hiding in the shack, subject to workplace accidents (Ventura, may indeed, have died in the 1970s and appear in the present as a ghost.) This gesture cuts across the time-frame. Ventura is no saviour—he’s more in search of salvation himself—but in this moment, reaching across time and towards another, he suggests the mutual embrace of solidarity and survival for those brought sometimes daily, face-to-face with death: those who might be best understood, not as the victims of capitalism, but its survivors. It’s through Tubarões’ recorded invocations of Cabral—and Ventura’s a capella repetitions of them—that Colossal Youth manages to convey the ghostly, unfulfilled past imaginings of a viable collective future that were still, in the early 1970s, a possibility: in the skipping, diegetic transmission of ‘Labanta Braço’ , that the ghosts of unfulfilled revolutionary promise are transmitted. Hiding from white supremacist police violence in the midst of a revolution that, for whites, promised a more general liberation, it’s Os Tubarões’ music that maintains (in both sense of that verb) the presence of Cabral’s drawn-out revolution in the colonies–a revolution that, as Cedric Robinson notes, precipitated the Portugese domestic revolution in dialectical fashion. The imperfect transmissions of a tinny recording; are containers for that which is not realised, the personal dreams of romantic fulfilment, the political dreams of Cabralism, of unity and liberty from imperial domination, from the far consequences of underdevelopment that extend far beyond nominal independence, or of immigrant integration into an apparently democratised metropole. It’s in these moments that the ghosts of leftist movements against political tyranny survive; in the catachrestic non-sequitur of skipping records, unanswered letters, unfinished revolutions, nascent worlds yet to be.

[89] Casa de Lava [Lit. ‘House of Lava’] / Down to Earth (1994, dir. Pedro Costa)

It was thanks to the filming of ‘Casa’ that Costa’s experience of encountering Cape Verdean migrants—relatives of those he met in Cape Verde, to whom he delivered letters on his return— radically changed his approach. Rather than the sympathetic colonial/leftist filmmaker travelling abroad, the director looks within: and rather than casting national narratives within the framework of fiction, embraces a collaborative approach shaped by the stories of non-professional actors themselves. Costa may be the public voice of these films; may be the one who puts them together, who frames them; yet without his performers, the films would not exist. This is more than the usual testimony to the power of the actor, shaping an already conceived storyline, script or conceptual frame, but the shaping of those elements by the performers themselves, a blending of realit(ies) that refuses the roles of subject-object, of documentary or fictional framing, but blends these roles in a more complexly collaborative fashion. That was to come, though. What of ‘Casa de Lava’ itself? Shot on Cape Verde itself, the film features a conventional—if ambiguous, stretched and dreamlike—narrative and the performances of professional actors, focusing on the figure of a white nurse (the Cape Verdean charge she accompanies literally mute), mediated through the intertextual references to Tourneur’s ‘I walked with a Zombie’ (itself the product of various racist myths concerning voodoo practice). It boasts compelling performance from Isaach De Bankolé as the patient—compelling even when reduced to a quasi-zombified state—and a hauntingly strange atmosphere, drawing in large part on the bleak power of landscape, something of an additional performer in the film. Impossible to tell how this film would seem without the knowledge of Costa’s subsequent work: one might say that Costa himself reduced it a footnote in his own career, as the question to which his later films provided the answer.

[88] Sans Soleil / Sunless (1983, dir. Chris Marker)

The key question, beyond revolutionary romanticism, is what happens after independence, Chris Marker wrote of Cape Verde when assembling for ‘Sans Soleil’ footage shot during the Angolan and Guinea-Bissaun independence struggle of the 1970s. For Marker, Cape Verde served as a potent figure for points of access, of entry or exit. Located in the central Atlantic ocean, and inhabited only upon discovery by Portugese explorers in the 15th century, it was the first European settlement in the tropics, and a key stopping point during the Atlantic slave trade, and its independence struggles during the era of decolonisation—along with its innovative linkage with the struggle in Guinea-Bissau, spearheaded by Amilcar Cabral—suggested new ways in which internationalism might be incorporated into a praxis of liberation. Likewise, the efforts of the Guinean filmmakers suggests what Cesar calls “the promise of a militant cinema of emancipation, born from the struggle as a praxis of liberation”. Yet in ‘Sans Soleil’, the Guinean archival footage, along with Marker’s images of Cape Verde, serve as indices of failed hopes, of the failure of both political struggle and the aesthetics of what he calls ‘revolutionary romanticism’ which invests in that struggle a hope for the future of the world. Over footage of Cape Verdean ports, queues at stores and labour on building sites or market places, Marker’s narrator comments: ‘Rumor has it that every third world leader coined the same phrase the morning after independence: “Now the real problems start.” Cabral never got a chance to say it: he was assassinated first. But the problems started, and went on, and are still going on. Rather unexciting problems for revolutionary romanticism: to work, to produce, to distribute, to overcome postwar exhaustion, temptations of power and privilege.’ Originally planning to make a film along the lines of the agitational, collective work developed with the SLON and ISKRA groups, Marker subsequently reshaped footage shot through the 1960s and 1970s into a video-essay meditation as much on his own role as on the broader narratives of which his footage provides a slice: a meditation on memory and on ways of narrating history, rather than that narrative itself. Including the footage shot by the Guinean filmmakers—Cabral embracing fighters, shaky black and white images that appear to be shot from within guerrilla conflict—Marker presents a doubly-lost moment of possibility, in which the documentation of African independence struggles by African filmmakers both fail. “Who remembers all that?” asks Marker’s narrator at one point, referring to the Cape Verdean-Guinean liberation struggle. “History throws its empty bottles out of the window”. Much of this filmmaking activity was lost when cannisters of film were thrown into the street during the civil war at some point in the 1990s. As Marker notes, hearing the stories of the sheer hell of such guerrilla warfare makes a mockery of those who described theirs as ‘guerrilla filmmaking’. If, at one stage Marker travelled the globe, documenting the revolution, documenting new modes of living–in footage that was, as in his early film on Cuba, often banned within Euro-American contexts–and emphasizing film-making as a collective process, later films like ‘Sans Soleil’ take the very same footage as the basis for the melancholic reflections which have as their overarching theme the failure of global transformation promised by radical movements in Europe and Third World struggles in Europe’s colonial ‘possessions’. The out-of-time nature of that footage, material to be re-inscribed, alternately written over or uncovered in a kind of politicised Proustianism, a palimpsestic reflection on defeat, needs as its corollary Marker’s science-fiction image of the future traveller, the traveller from the year AD 4000 in which earth has become a world of total recall, viewing with compassion the sadness mixed with aesthetic pleasure–the forms of art, of cinema, the failures of memory and desire. Noting the problematics of the gaze he projects onto the Cape Verdean women he films until they cast their gaze back at the camera, Marker ends his film on the image of the Cape Verdean woman who locks eyes with the camera for a fraction of a second–the exact length of a frame of film–Marker appears to hold this out as a possibility, if not of mutual contact, of the resistance to objecthood, and the possibility of a self-creation that would not need the mediation of the white, male filmmaker, world-traveller, revolutionary romanticist. Yet, as with much of the footage in the film, Marker feeds these images into the image-synthesizer of the (fictional) Japanese artist Hayao Yamanoko, producing solarised, distorted images that distort and transpose their sources into blotches of irreal colour and indistinct, amorphous forms. Feeding the footage into the machine serves as a surreal analogy for the mediations that exist between filmmaker and object, the problems of colonial framing, and the vagaries of historical memory, that are Marker’s subject. The returned gaze, the flicker of tacit acknowledgment of performance, suggests the possibility of an artistic response–to frame oneself, rather than to be the always-framed—a fragile, yet vital force against the power imbalances of a ‘world cinema’ whose legacies are still firmly rooted in colonial power relations.

[87] Glauber O Filme, Laborinto do Brasil / Glauber the Film, Labyrinth of Brazil (2003, dir. Silvio Tendler)

This documentary centres around footage of Rocha’s funeral, with the conceit of Rocha’s life and work as a ‘labyrinth’ that mirrors that of Brazilian politics and culture—the labyrinth in question rendered in cheesy computer graphics that pale in comparison to the technical means of Rocha’s films. As such, it places personal legend—easily encouraged by Rocha’s larger than life personality—over the specifics of his films, though there’s sometimes useful information from the talking heads. Probably neither the best introduction to Rocha’s work nor a particular in-depth or satisfying experience for those who know it better—but perhaps that mid-range is what it’s after. That said, any reduction of the wild cinematic ‘poetry’ of Rocha’s films to the ‘prosaic’ form of the talking-head documentary is going to entail an unavoidable reduction, and the labyrinth conceit is at least imaginative. And certainly, it’ still a vital resource those interested in Rocha’s work—particularly given the difficulty of getting hold of the other major Glauber documentaries such ‘Anabazys’, directed by his daughter Paloma focusing on ‘O Idade do Terra’.

[86] A Idade do Terra / The Age of the Earth (1980, dir. Glauber Rocha)

Given the difficulties he faced in assembling money to make films, and the obscurity of those he did manage to make, Rocha’s outspoken media presence had been his major role since 1969 at least, and it now entered into the films. This is a key weakness: a kind of egoic messianism, losing more and more political sense as he praised military dictators, with scenarios for ambitious films which could, in all likelihood, never be made. Both epic summation of Rocha’s career and an incoherent end-of-the-line, ‘A Idade’ is like almost nothing else in cinema. We find one more the allegorical figures whose interactions are epic and poetic rather than realist, though we’re also presented with near-documentary scenes, interviews and chaotic, seemingly improvised moments which appear closer to performance art (or, to be less kind, amateur theatre). Rocha claimed that the reels of the film could be shown in any order—history as linear order is firmly rejected for the repetitions and non-sequiturs that are held in place by mythic overlays which at the same time provide the fulfilment and solution to history. Is this a mystical escape from reality, the result of political impasse? Absolutely. But at times it’s no less breath-taking for that. The allegorical forces this time are four ‘Christs’ who are also the four horsemen of the apocalypse, St George, and so on, and their female counterparts—Aurora (sunrise is an important figure for the film), Magdalena, the queen of the Amazons. A businessman-imperialist, the hulking and Aryan ‘John Brahms’ staggers through the city in hysterical displays of sadistic power. These figures move around in public spaces in sequences that appear improvised, shot amongst traffic or in crowd scenes with puzzled onlookers, or in cramped interiors with Rocha’s own voice shouting offscreen at the actors to scream their lines ‘ten times louder’. Rocha further destabilises time by often including multiple takes of the same lines, repeated as many as five times—the ‘military Christ’ sitting in front of a café and proclaiming that, even if he uses violence and ignores human rights, he upholds essential ‘spiritual’ rights—and what would appear to be ‘outtakes’—Brahms collapsing and apologising to Glauber for his weaknesss; Rocha’s infant daughter banging at a piano. The shifting alliances of the film’s allegorical figures, in their gendered pairings and their various speeches, provide uneasy mapping of betrayal, power and, at times, possibility. The gringo imperialist, Brahms, appears perpetually on the verge of collapse, yet that collapse never comes: political stasis is the overwhelming feel, despite the surge of action and event and the promises to provide a more democratic future Brazil, couched in the language of mystical, syncretic Christianity. This is a paradoxical teleology without end in its interchangeable reels, the film can have no conclusion. In what is probably the film’s key sequence, Rocha yells out an incoherent voiceover speech to footage of the ‘Black Christ’ as St George, holding aloft a garish Expressionist icon of the crucified Christ, in which he claims the ultimate political ambition should be to defeat death itself. Rocha’s voiceover—which, in its halting pauses and streams of language, sounds improvised rather than scripted—explains the genesis of the film as a life of Christ inspired by Pasolini’s murder. Pasolini serves as the corpse from which a new, third world Christ can emerge, as Rocha preaches an incoherent political gospel in which a transformed Christianity serves as the beacon of global hope, along with a vision of Brazilian ‘democracy’ that functions beyond ‘capitalism, socialism, communism’. This utopian, ultimately nonsensical vision—which also claims that the ultimate political ambition must be to defeat death itself—has to be expressed in manifesto-like words in order to give some coherence to what see onscreen, even as the film itself seeks for a visual ‘trance’ based on fragments of language, overwhelming and jarringly intercut blasts of sound, from Villa Lobos to carnival music and improvised free jazz, that rejects the cohesion Rocha’s speech seeks to impose. The whole film is a total blaze of overkill—too loud, too long, with the maximum of excess as fundamental methodogical starting point—that cannot and does not end. Ismail Xavier call this the limits of national allegory as methodology—while apparently mythic structure presented in Rocha’s previous films is ultimately grounded in a historical basis, it fails when it comes to the present of the 1980s, of a decade lived under military dictatorship. Rocha in essence admits as such in his voiceover description of the utopian city project of Brasilia, an analogy, it would seem, for his own film: “strong irradiation, light of the Third World, a metaphor that doesn’t come true in history, but meets a feeling of greatness, the vision of paradise”. This is a matter of faith: but faith, while it might at times seem the only possible way to survive a dictatorship with no end in sight, is hardly adequate on its own. Unable to account for the profusion of elements brought into the audience’s view, ‘A Idade’ asserts the positive force of Brazilian syncretism against the violence embedded in its history and as a way beyond the crippling underdevelopment fostered by American imperial interests in the region. But this nationalism—even if it seeks to counter the mendacious nationalisms of religious and military power—ultimately cannot see a way out of them, falling prey to a disunited model of national unity that veers near to complicity with the repressive forces that governed the nation, against which Glauber might at times have staked his life.

[85] Cabezas Cortadas / Cutting Heads (1970, dir. Glauber Rocha)

The more Glauber Rocha talked about cinema, polemicizing in the pages of Brazilian and European film journals throughout the 1970s, the less well-received were his actual films. His European-made films, in particular, are very rarely discussed in any detail in English language criticism, and almost never seen more widely. ‘Cabezas’ may be one of the most obscure. In some ways reminiscent of the Pasolini of ‘Porcile’ and ‘Teorema’—in its casting of Pierre Clementi, in its bleak Mediterranean landscape, and its staging of a drama engaging with syncretic mythology—it also seeks—as did Pasolini’s ‘Medea’ and ‘Oedipus’—to examine and counter the focus on tragedy with the Greco-European tradition. In ‘Der Leone’, the violence undertaken by allegorical figures was a clear parallel to Third World revolutionary struggle; here, it forms a kind of mythic overlay which at once suggests revolution and king-killing, while focusing on pagan figurations of death and rebirth, of cyclical renewal. Shakespeare’s Macbeth—a key study in political power and the transition from feudalism—is used to suggest the dynastic drama through which exiled dictator Porforio Diaz—at once Juan Peron, Batista, and Franco—understands his own role. Macbeth-Diaz comes to stand for the thanatopic force of western tragedy, an infantile irrationalism disguised as rationalism through the desiccated trappings of ceremony—crowns, telephones, horses, swords, scenes of foot-washing to an interminably repeating ceremonial dirge. The severed heads of the title are, perhaps, the heads of ‘reason’ (the Greek bust paraded in front of Diaz in the mud), echoing the seven-headed beast invoked in ‘Der Leone’—as well, of course, of the decapitation of the king whose rule is over ‘Cabezas Cortadas’ was financed by a Spanish communist filmmaker and producer Ricardo Munoz Suay and shot in Spain. Ironically, Rocha moved from one country in which the dictatorship had begun to clamp down on film production to another where Franco existed enormous censorship power (Bunuel, whom Rocha cites as a key influence on this film, ahd gone into exile in Mexico in the 1950s—details). Yet because the film was not overt in its references to Francoist Spain, it escaped censorship there, though it was censored in brazil and could not be shown until later in the decade. Though the film lacks the oral saturation of Rocha’s other films, it is punctuated throughout by fragments of popular songs such as ‘Sabor A Mi’—also borrowed for the unforgettable book of poetry and visual art by another South American exile, Cecilia Vicuña, a couple of years later. These songs are sometimes sung by Diaz, sometimes by members of the collective group representing ‘the people’: they are zones of contestation. In the film’s conclusion, Clementi’s silent scythe-wielder has executed the old king and crowns a figure aligned with the Virgin Mary, while the crowd sing a song of faith, healing, death and rebirth. The crown is held up both as a tool to be replaced (kingship as such) and as something ambiguously to be taken up. One of the people could step up and become the new dictator, or they could remove the king function altogether. Myth keeps repeating, but perhaps each successive repetition will break out of the cycle, while avoiding the disastrous suppression of the past.

[84] Der Leone Have Sept Cabeças / The Lion has Seven Heads (1970, dir. Glauber Rocha)

Ironically, it was at the height of his fame as an exponent of a specifically cinema that Rocha was exiled from Brazil and began to operate within a European framework, seeking funding wherever he could. ‘Antonio das Mortes’ had effectively put Brazil on the international (read: European) cinematic map, providing a populist left-wing icon that combined the appeal of the ‘Zapata westerns’ with that of the left-leaning arthouse crowd, coincided with Rocha’s (self-imposed) European exile, yet Rocha was now cut off from the folk practices which gave his early films their force: the cangaceiro myths of ‘Antonio’ and ‘Black God’, the cadomblé of ‘Barravento’. His embrace of identity as a ‘tricontinental’ filmmaker, and consequent depiction of the Third World thus in turn becomes more generalised, at once suggesting solidarity along the lines of tricontinentalism, and reflecting an unmooring from the specificities of Brazilian cultural production. During the 1970s, Rocha shot films in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (‘Der Leone’), Spain (‘Cabezas Cortadas’) Italy (‘Claro’) and, as part of a collective production, the documentary ‘As Armas e o Povo’ on the 1974 carnation revolution in Portugal. In other words, he participated in the political questions both of the European ‘West’ (including its dictatorial, military aspects) and the decolonising ‘Third World’. Beginning with ‘Der Leone’, Rocha gives new meaning to the term ‘international coproduction’. If this new confluence of state and private funding arose in part from the inability of national cinemas to compete with Hollywood, it also enabled the production of a notably left wing, third wordlist cinema—the ‘Zapata westerns’, films like Bertolucci’s ‘Novecento’, Pontecorvo’s ‘Battle of Algiers’ and ‘Quiemada’. The film’s cast is international and, though the film is shot primarily in French, each the five languages that form its title are also spoken. Rocha thus insists, while operating from a perspective informed by the particular experience of brazil, that the film is international, in terms of filmic influence—he mentioned Brecht, Einstein and godard in relation to this film, along with cinema novo—and the issues of colonialism, an international phenomenon. ‘Der Leone’ differs from almost all existing models of political cinema: the Maoist—but white and European—left found in Godard’s work from ‘La Chinoise’; realist depictions of revolution (Pontecorvo); neorealism; the attempt to create empathy for the struggles of the oppressed. Instead, he turns to allegory and dream, not just as one element, but as influence on total structure, at once stressing the technological mediation of cinema in a firmly materialist manner and insisting on the importance of an apocalyptic, revolutionary mysticism to its conceptualisation of politics, resistance, revolution. Thus, Rocha at once emphasizes the defamilisarising—‘modernist’—elements of his previous work, bringing together a secular, materialist tradition—Brecht, Godard—with the ecstatic, the mystical and the musical that differed sharply from such models. If Rocha’s Antonio films had borrowed their figuration from existing folk myth and, to a lesser extent, film trope—St George, the cangaceiro, the landowner, the cowboy—the allegorical canvas here is broader and more international. Unlike Godard—who avoided Africa—or Pasolini—whose African and Arabic settings were, to say the least, romanticised—Rocha took seriously the possibility of Africa as part of the tricontinental axis. His African extras are not anthropological specimens but real people, sometimes laughing at the actions they’re asked to perform: in one key moment, the camera zooms past the European actors and lingers on the faces of the crowd who watch them with a kind of defiant bemusement that extends to the filmmaker himself. The scenarios sees the tricontinental revolutionaries—associated with Zumbi, the Black Brazilian founder of the quilombo community Palmares, with African leaders such as Cabral, and with Che Guevara—unite against Marlene, the Aryan figure identified with the seven-headed beast of the apocalypse and with the mendacious forces of money and European colonial ideology, and her henchmen—a series of European mercenaries and the neo-colonialist ruler from the African national bourgeoisie. At the films end, a procession of militants in guerrilla fatigue slowly march up the hill, singing a revolutionary song. The protagonists of ‘White God’, Paulo in ‘Terra em Transe’, or Antonio in ‘Antonio das Mortes’, who end those films stuck on the edges of things with no way out—the coast, the desert, the endless road—with no way out. Here, however, the militants, unlike those isolated figures, move as a group and march with a purpose, even if it’s not clear where they’re heading. Moreover, their song unites art and struggle: the song and the machine gun, the spear and the dance are connected. Rocha’s exilic internationalism is thus refigured as space of possibility as well as the product of political catastrophe. At this point, there was evidently a world to win.

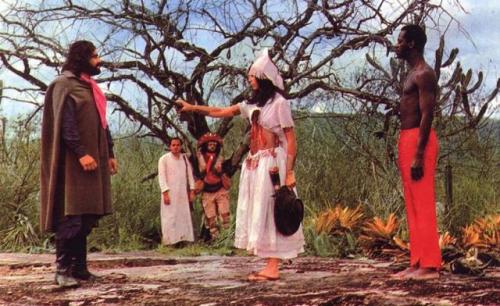

[83] Antonio das Mortes (1969, dir. Glauber Rocha)

Back to the sertao after the world of urban politics in ‘Terra em Transe’, this, perhaps Rocha’s best known film, focuses on selection of archetypal figures: the cangaceiro and the black male saint (Saint George) and white female saint who accompany him, opposing the landowning coronel—representative of the old order, losing his grip—and the modernising underling who attempts to enact equally exploitative land reforms with US investment, with the bounty hunter Antonio das Mortes, who kills the last remaining cangaceiro, realising the errors of his ways and joining with the group of followers now deprived of their leader, while also realising his own ultimate irrelevance, as a positive force, to their struggle, as he trudges along, alone, by the side of the road the bears the trucks associated with U.S. imperialism. The film ends ending in a kind of parody of the western shootout, opposing the heroizing idea of violence as redemption, yet drawing on violence and archetypal forces of good and evil such as St George and the dragon drawn from folk myths as collective and syncretic modality. Rocha noted that, in an underdeveloped, rather than modernised country, Brazilian uprisings came from slaves and peasants, not from the proletariat. In Rocha’s films, people speak in poetry. Rocha draws, not on the ‘naturalistic’ dialogic modes of neo-realism but on the heightened discourse of oral tradition, of folk poetry, of song. As far back as ‘Barrevento’, dialogue is less narrative, functional or naturalistic, than a mode of ‘theatricality’ closer to the traditions of ritual, religion and folk practice, of folk drama—as well as to Brechtian and avant-garde techniques, insofar as these might also be informed by such practices. These films are symphonies of sound and image, intermedial works aiming to create an aesthetics of film that is not based on an aesthetics of the natural, the psychological, the narrative or the linear, but a canvas writ larger than life. Rocha, as a middle-class Protestant filmmaker from the city who comes to endorse a form of syncretic rural folk Catholicism associated with the sub-proletariat, to an extent overlaps with Paulo Martins from ‘Terra em Transe’—the relation of the filmmaker to often desperately poor subjects, such as the extras who give ‘Antonio das Mortes’ much of its life, is one at once of class contradiction, solidarity and potential exploitation. While Rocha at one point claimed to be ‘psycho-analysing’ the traditions of the people—an ambiguity that echoes that of Fanon’s writings on folk practice within decolonising movements—his films suggest something less clear-cut, an attempted fusion with those traditions that doesn’t pathologise them, but uses them to reorientate the language of reason itself. The focus on the north-east, on peripheral regions, also had ramifications in terms of the film’s material circumstance. During the shooting of ‘Antonio’, Rocha and his left-wing crew, on location in Brazil’s Northeast, faced a choice: either return to the urban centre and likely be jailed, tortured, or killed; or stay where they were and finish the film. The decision was made: both in terms of personal survival and political effectiveness, the film was paramount. Its legacy, a kind of folk opera of shifting imagery and sound, is a vital contribution to Cinema Novo, to Third Cinema, to cinema in general.’

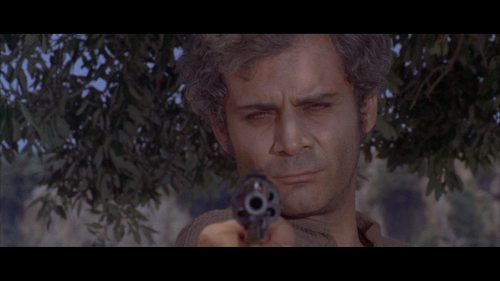

[82] Terra Em Transe / Entranced Earth [Land in Anguish] (1967, dir. Glauber Rocha)

Rocha here focuses, not on the underdeveloped peripheries of the country, but the centres of urban political power. As a film, its editing, shot composition and soundtrack bring it closer to the vocabulary of the European New Wave—whose experimentation is taken a step further in a barrage of visual and aural information—and its focus on an alienated poet-intellectual, torn between class loyalty and a sense of justice, certainly fits with the paradigm of the European art film. The intellectual in question, Paulo Martins (on the right of the photo above) respectively aids, then turns against, first a right-wing Catholic nationalist and then a left-leaning populist politician (in the centre), both disgusted by and exceeding them both in cynicism and contradictory political moves. The forces of American capital hover all the while. Alternating between the allegorical—conducted in something of the vein of street theatre, as the relations between different class interests take vividly archetypal form—and moments closer to realist dialogue, the film also stages numerous confrontations between art and action, the pen and the gun, our ‘hero’ beginning and ending the film by writing his cryptic, surreal words in the sky with a wildly-brandished machine gun after the military coup which has seen him fatally shot in an escape attempt. So Martins is another Rocha protagonist fleeing, caught between contradictory forces—but the populist energies of the underdeveloped are not present here. This is, instead, a record of a catastrophic series of moves which ensured the decades-long military dictatorship: the overthrow of the Goulart government in 1964, and the cementation of military power in the constitutional changes of 1967. Myths are shown, not as revitalising forces, but as those wielded by corrupt figures—the Catholic politician evoking the missionary zeal and religious fanaticism of the original colonising forces and of the Inquisition—against which a secular intellectual class has little to no reply. Only the activist Sara (left of the photo above), who’s been tortured in prison and who, in comparison to her sometime lover Paulo, refuses to waver in her commitment to the struggle, provides a voice against such catastrophe, juxtaposing Paulo’s ‘hunger for ideas’ with the presence of actual hunger, his ‘tortured’ mental struggles with the actual torture she faced in prison. If it’s often unclear what viable forces are left to which one can commit after the advent of a dictatorship, it’s the fact of this commitment that lingers.

[81] Deus e o diabo na terra do sol [Lit. ‘God and the Devil in the Land of the Sun’] / Black God, White Devil (1964, dir. Glauber Rocha)

Where do the protagonists of ‘Black God’ run to? They—a husband and wife on the run—have spent the whole film fleeing–from the murder of the boss who refuses to pay for dead cows which first renders them fugitive, to the murders committed for and eventual murder of the religious leader (the ‘Black Saint’ of the film’s English title) they next take up with, to the murders committed for and the death of the cangaceiro, the folk bandit (‘White Devil’) who provides a further . Each unit in which they find themselves in some way offers an articulation, however imperfect, for their struggle against the social forces that exploit them and keep them in poverty: the religious cult given over to millenarian prophecy, to brutal tests of strength, and to acts of violence which seem at once forces of social justice and indiscriminate, fanatical killing, the cangaceiro’s gleeful proclamation of ‘evil’ and war against the owner classes equally prey to displays of egomaniac male power and sadistic brutality. Once these are destroyed by the state, in its own acts of brutal violence which slaughter the cult members on the mountain where they’ve prayed; once the cangaceiro is dead, tracked down by the ambiguous bounty hunter Antonio das Mortes—a kind of class traitor maintaining ‘law and order’ through extra- (or semi-)legal violence whose ‘conversion’ to the cause of the people will form the basis of this film’s internationally-successful sequel—their only resort seems to be the sea itself, the farthest limit of the country, the point of no return. The sea is a vital location in Rocha’s work: as the scene of the birth of modern Brazil, of violence and colonialism: the suppression of native populations, amplified in Rocha’s next film, ‘Terra em Transe’, as the right-wing politician strides onto the beach, the flag of the Inquisition in one hand and a cross in the other, and the imported labour of the slave trade—present through the cadomblé register of ‘Barravento’. For its part, ‘Black God’ strains throughout at the limits of the coast, of arid interior and marine exterior. The film’s ‘black saint’ repeatedly claims that the sea will merge with the sertao (the arid farmlands of the country’s underdeveloped northern regions in which the film is set). This impossible union suggests a tension key in Rocha’s work: between the succeeding waves of invaders, at once exploiters and exploited, from the indigenous population, to African slaves, to the ‘white’ poor, to the ‘white’ modern urban bourgeoisie. For the sea—the space of those who are racialised (the Black fishing community of ‘Barrevento’ or the white coastal cities that give Brazil its international image)—and the centre—a region of intense underdevelopment. Coasts are places of arrival and departure, a reminder of Brazil’s European colonial past and the underdevelopment which renders that tension still present. Rocha went on to a career staked on his internationalism, as a self-proclaimed tricontinentalist who went on to make films in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in Italy, and in Spain. But his friend Regis Debray nonetheless suggested that Rocha always approached both politics and aesthetics through the lens of revolutionary nationalism: the coast as a figure for the landings and departures that could never quite be fully made, or never made without violence, rupture, fracture, an aesthetics of dreaming that might equally become an aesthetics of nightmare. Where do the protagonists of ‘Black God’ run to? Everywhere and nowhere. Their lack of options attests to an ever-present dilemma, all the more so, a good half-century on, in the age of Bolsonaro, of the continued super-exploitation of native land, of ever-more brutalising racism and alliances with American capital: the question of a political future, and the available means of a national cinema with which such a future is intimately connected. The protagonists’ descendants might be said to symbolically run down that coast still.

[80] Barravento (1962, dir. Glauber Rocha)

In a sense apprentice work—a production taken over when one director abandoned the project, and in turn abandoned to be completed by a third—this film is both an anomaly within Rocha’s output and an important anticipation of his later concerns. His first engagement with folk practice and syncretic religion—here cadomblé, in other films, its Christian inflections as they manifest in the mythic figure of the ‘black saint’, St George—is markedly ambivalent, even downright hostile. Yet it’s vital to make a distinction between the didactic dialogue which calls for the rejection of superstition from a materialist, socialist basis, and the energies to be found within those ‘superstitious’ forms as they’re documented by the camera—the chants, drumming and singing that will provide such an important part of both texture and argument in ‘Antonio das Mortes’. This distinction suggests a contradictory—though possible generative—ideological conflict beyond that staged in the film’s narrative. Members of the fishing community can proletarianise themselves by moving to the city and learning methods to join their struggles to those of the workers’ movement—in particular, circulating around the ownership of the nets with which they fish, ‘loaned’ to them at extortionate prices by urban capitalists. Thus, the film’s ambiguous hero, who’s begun the narrative by returning to the village from an initial period in the city, full of contempt for its ‘backwardness’, leaves once more with a resolve to help transform that community. Yet along the way, he’s shown himself morally dubious in his actions—at once castigating and hypocritically using the forces of cadomblé ritual he castigates in ways that map onto sexual desire and conflict. Rocha’s subsequent films will learn to move from an aesthetics of hunger to an aesthetics of dreaming, to use his terms—from the representation of poverty to an attempt to derange style itself in a way that gains from the insights of the oppressed (including, and perhaps especially, the ‘superstitious’ repository of imagery to be found in folk religion) rather than simply presenting their oppression as disaster to be solved by the science of dialectical materialism. The film itself lacks the visual excesses of Rocha’s later work, its narrative at least ostensibly cleaner and more coherent, its visual language less extreme, its palette one of black and white contrast that lacks either the bleached bleakness of ‘Black God, White Devil’ or the explosion into colour signalled by ‘Antonio das Mortes’. Yet moments are as haunting as anything in his filmography—a drumming circle upon the ‘hero’s’ return—the space of the sea as location of trauma and possibility, from whence the titular figure of the ‘barravento’ or ‘turning wind’ provides a metaphysical transmutation of the originary forces of the Middle Passage. As such, it suggests a relation between the (largely Western) vocabulary of vulgar Marxism and the racialised presence on the peripheries of the nation, granted a degree of semi-independence that both arises from and challenges conditions of underdevelopment. And it’s to a synthesis of these forms that Rocha will increasingly reach towards: a rejection of coherence that stresses improvisation, energy, and the potentiality contained within aesthetic/religious forms that cannot be subsumed to ‘scientific’ laws.

[79] Aruanda (1960, dir. Linduarte Noronha)

For Cinema Novo figurehead Glauber Rocha, Noronha’s short, semi-documentary film was the foundation, presenting an ‘aesthetic of hunger’ against the ‘aesthetic of digestion’ (and consumption) that governed the myth-making of official Portugese cinema, which it countered with “characters who eat dirt, characters who eat roots, characters who steal in order to eat, characters who kill in order to eat, characters who flee in order to eat, characters who are dirty, ugly, skinny, living in filthy, ugly, dingy homes”, and for which it was criticised of ‘miserablism’. But the family shown here are not simply victims: the film shows their impulse to continue, to survive, to build; humour, intimacy, humanity. They’re the survivors of a quilombo, the descendants of those who ran away from the slave regime, and though they have to survive within a semi-arid landscape, their separation from an affluent urban landscape within underdeveloped regions an index, not only of their defiant legacy, but of the continuing racialised, classed and regionalised imbalances of Brazilian society. The film presents those who have refused and have been refused ‘integration’ into the broader body politic: its title suggests the Afro-Brazilian religious conception of a spirit world, of embodied spirits who take the form of the ‘wretched of the earth’, a syncretic form with political ramifications. As such, it gestures towards the revitalising myths which Rocha will find in such communities, which serve to present hunger and misery, not in fatalistic fashion, but as a dialectical source for new myths, new ways of political and cinematic thinking.

[78] Monangambé (1968, dir. Sarah Maldoror)

Maldoror’s ‘Monangambé’ plays out a similar scenario to the feature-length ‘Sambizanga’: the visit of a wife to her imprisoned militant husband—with a more darkly comic frame and a more avant-garde soundtrack and visual style serving to illustrate both the extreme brutality of the situation, the ironies of paranoid misunderstanding, and the psychological effects of torture (in the shadowy scenes of the imprisoned man traumatised by torture). Its title—a warning, literally meaning ‘white death’, of the approach of slavers, and subsequent colonial powers, and then as signal to gather during the liberation struggle of the 1960s—performs a linguistic reversal suggesting the importance of contextual knowledge, and it’s this sense that the oppressed can utilise language as a weapon that remains opaque to the colonialists that leads to paranoia such as that seen by the prison authorities here. The prisoner’s wife promises him a ‘complet’—that is, a three-course dish, food for someone deprived of proper nutrition—misunderstood by the prison director as a three-piece suit, and thus as the reward for escape from prison, leading to renewed sessions of interrogation and torture. At once stroke, prison authorities exercise near-unlimited power within the confines of their domain, sadistically wielding torture whenever they feel like it, and are revealed to have little true understanding of what they’re dealing with—a misunderstanding that can perhaps be exploited. The soundtrack by the Art Ensemble of Chicago emphasizes discontinuity over mimetic guidance, the independent parts that constitute the individuals within a freely improvising ensemble, and of the tracks of visuals, soundtrack and speech that constitute a film. This is a film about the risky ambiguities of language and of the emotional truths that go beyond language, not as existential concerns, but as the arena of real political struggle, of real consequence, for which cinema finds an experimental vocabulary. Maldoror’s films of this period are films in process—films subject to an extreme precarity of material circumstance, such that an entire film might be lost mid-way through film-making, which are forced to improvise and adapt in their methods, and which suggest a kind of improvisatory viewing as well. Virtually unseen within the canonical habits of Western film consumption, they’ve lost none of their power.

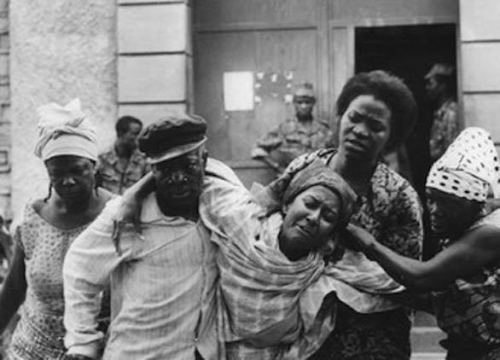

[77] Sambizanga (1972, dir. Sarah Maldoror)

Maldoror’s vital film was made for practical purposes—to document the struggles of the Angolan War of Independence, and the widespread imprisonment and torture of members of the MPLA, at a time when the war against Portugese colonialists was by no means over. With its cast of non-professionals and its absence of visual flourish, Maldoror’s film emerges from and speaks to its circumstances: functional film-making, which doesn’t mean a suspension of ‘quality’ for the contextual, but which makes a strong claim for a mode of cinema that cannot be disentangled from ‘context’, in which form and function match. The film is neither the exposée of neo-realism nor the humanist of ‘poetic realism’, but something entirely its own. The scenario is simple, but has its heart the willed obscurity of a colonial regime who lock away and murder those who challenge them in secret: Domingos, an MPLA militant, is abruptly kidnapped by colonial authorities in a horrific dawn raid of the village; his wife Maria walks from prison to prison, and the film follows her journey, and that of a network of clandestine militants who seek to obtain information on Domingos’ location while themselves remaining ever-careful to avoid exposure. It’s a woman—Maria—and an old man and a young boy—the pair who watch the prison for those who have been secretly deposited there—who form the central points of identification, and while a superficial viewing might suggest that the film reinforces normative gender roles—Maria’s entire focus is on her husband, rendering her in that sense secondary to a political struggle figured as male—that would miss the point. Maria’s grief and uncertainty is genuine, her task is practical: screaming Domingo’s name outside the prison is a practical, political act, as well as a raw welling-up of grief. And the collective network which seeks to aid her, and which can only emerge through mediated forms of communication, the slow process of connection, the discovery of information piece by piece, involves men, women and children, suggests a model of the society that might emerge once the struggle is one, eventually coming into focus in the closing performance of song, a public statement of solidarity and resolve, a joyful memorial for the dead. Made ten years after the events it describes the film is able to close with end titles that note the progress such struggle ensured, even if that struggle has by no means by entirely won. Though Domingos dies, Maria’s persistence, along with that of the network of other militants who receive the news of his death, and who will soon go on to storm the prison, suggest qualities of survival and defiance that assume both a personal and a collective level. A luta continua.

[76] Hyènes / Hyenas (1993, dir. dir. Djibril Diop Mambéty)

After the twenty-year period of silence following the success of ‘Touki Bouki’, Mambéty’s second film gives its satire a more analytical frame. The quasi-allegorical narrative structure explores the relation of past to present within a specifically—though exaggerated—political frame; its events are specifically set in a collective context, where the continuing legacy of imperialism as it effects relations gendered, sexual and economic relations in the (post)colony. Returning to her village as a fabulously wealthy citizen, for whom wealth is also index of damage, literal prosthesis—the arm made of gold!— Linguère Ramatou is something like ‘Touki Bouki’s’ Anta some decades on, returned to take revenge on Dramaan Drameh, the man who abandoned her and has since taken up a role as a comfortable, well-liked bar owner—and a kind of de facto, unofficial mayor—within the still impoverished town. The devil’s bargain—that her wealth will be that of the village if they execute him—is not only index of personal revenge, a kind of just deserts for the past sins of patriarch—Drameh paid false witnesses to testify that he was not the father of her child, leading her to be driven out of town and to a career as a sex worker—but of the inhuman and dehumanising bargains of global capital, the mendacious ways in which continuing underdevelopment and the power relations of the centre-periphery relation structure the life it’s possible to live. Ramatou simply serves as the agent of the ways in which collectives are divided—whether by the structures of gendered power relations or by the ‘hyena-like’ rapaciousness the promise of money brings. Such economic structures rely on the mythic realities that any dream can be bought, and that its fulfilment will invariably come at the expense of others. Through a satirical broad-brush, Mambéty seeks to make such bargains specific, rather than the abstract underlay of virtually every human interaction; it makes a vivid and convincing case whose laughs have the sting of accuracy.

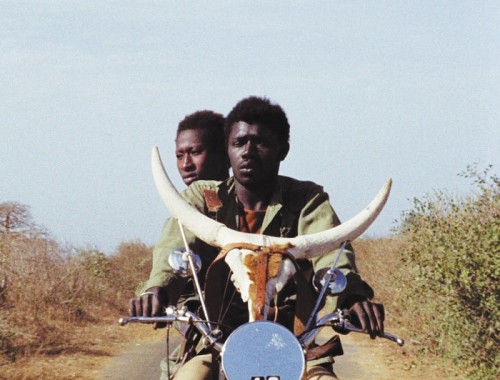

75] Touki Bouki / The Journey of the Hyena) (1973, dir. Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Young couple Anta and Mory roam around on a motorcycle and try to think of the best way to steal a large quantity of cash in order to escape to France, their dreaming of Paris is rendered on the soundtrack through the increasingly grating fragment of Josephine Baker’s ‘Paris, Paris’ as leitmotif, an incessant loop, the siren call of the metropole to which only one will ultimately respond when it’s time to board the ship. The film constantly jump-cuts between subjective impression and objective frame, occupies the gap between dream and present circumstance, the rebelliously joyful and derisive rejections of anarchy of the equally unmoored drifting of the disillusioned. Structured around a loose narrative—more wish than fulfilment—its satirical exaggeration occurs somewhere between reality and fantasy, surreal flickers at the edge of the observed that borrowing their visuals both from the iconography of cinema—the motorbike, with its unforgettable cow-horn mounting rendering it something from an adapted western, the various illegal schemes to get money with their suggestions of the Hollywood outlaw—and from public life and its presentations of wealth and power—the sequence where our heroes imagine themselves as politicians in a gaudy parade—but also, in less self-contained a manner, in the truncated evocation of the way that personal emotion blurs, cuts and slices clear and logical narrative, as in the early sequence when Anta believes Mory to be dead, fallen off the cliffs, loss and death soon turning to erotic encounter. Caught between unattractive options, with few prospects in site, the rejection of the alienated despair of expected social roles and routes leads to a different sort of alienation: aimlessness, drifting, being, escaping through the freedom of the road, Easy-Rider style—a freedom that ultimately seems to lead nowhere, the bike totalled by a thief who lies dead in the road. These dreams are haunted by death—from Anta’s mistaken grief to the film’s most notable icon, the cow-horn mounting, itself contextualised by the opening sequences of a slaughterhouse rendered in unsparing detail. That’s not to say it’s fatalist or existential, but neither does it seem to place a huge amount of belief in cinema as educational tool found only a few years earlier in Sembène’s ‘Le Noir De…’, widely cited as it is as the first full-length independent production on the African continent. Open-ended and ambiguous, ‘Touki Bouki’ doesn’t construct an argument or make a plan, and its near-nihilism perhaps what rendered it attractive to precisely those Hollywood filmmakers (Scorsese) whose exploration of crime and defiance it recontextualises and plays back. But unlike those films, its tone—at once brash and elliptical, satirical and melancholic—has rarely been matched.

[74] Le Noir De…/ Black Girl (1966, dir. Ousmane Sembène)