Jürg Frey: clarinet // Radu Malfatti: trombone // Angharad Davies: violin // Dominic Lash: double bass // Sarah Hughes: zither // Kostis Kilymis: electronics

Jürg Frey: clarinet // Radu Malfatti: trombone // Angharad Davies: violin // Dominic Lash: double bass // Sarah Hughes: zither // Kostis Kilymis: electronics

"The being ensemble, or together, does not merely depend on the accuracy with which each reads his part, but in the intelligence with which he feels its peculiar character and connexion with the whole; whether in the exactitude of phraseology, the precision of the movements, or seizing the instant and degree of pianos and fortes..." // The London Encyclopaedia, Or Universal Dictionary Of Science, Art, Literature And Practical Mechanics, Comprising A Popular View Of The Present State of Knowledge. (In Twenty-Two Volumes. Vol. VIII. 1829.)

But this is part of the hierarchical model of (musical) ensemble: later in the same passage we read, “It belongs to the masters, conductors, and leaders of an orchestra, to guide, check, or accelerate individual performers, and to keep them together.” Now the model of musicians reading from a score, guided by composer and by conductor, is not something that one must necessarily reject in its totality, as was vigorously asserted some of the more vehement statements from that generation of free improvisers who first began to formulate their methods in the 1960s; of course not. But note the term “masters,” the assumption that ensemble, or chorus, implies subordination to a leading, guiding light, the masses under their king, their judge, their chief of police, the ultimate arbiter of taste. Leadership within the improvised ensemble is crucial within African-American improvised musics departing (following on from) jazz: no one challenges the leading roles of Cecil Taylor, or Sun Ra, or Anthony Braxton, within their ensembles, as dictatorial imposition. Yet might we not also (‘also’, rather than ‘instead of’, because no model is absolute), find some mode of accommodation between composition and improvisation, the following of a score and the space for the individual interpretation of a particular line, in a leader-less mode of ensemble-being, or being-ensemble, which follows on from the enacted anarchy of John Cage’s late ‘number pieces’?

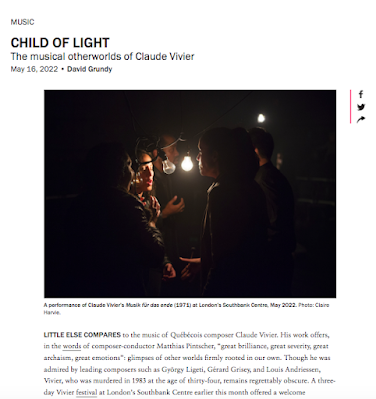

Such questions pertain very much to the concert held, on June 28th, at St Columbus Church in Oxford, organized by Richard Pinnell, and featuring a sextet of musicians in composed and improvised work falling somewhere within the territory marked out as ‘Wandelweiser’ music. Before entering the write-up proper, I should thank Richard for putting on this event, and for the clear effort of thought and care expounded in its presentation. One got the sense that the occasion as a whole – and the printed programme which accompanied it in particular – was his attempt to work through concerns latent in the critical reception of this work over the past couple of years, but not often explicitly made the exclusive focus of discussion – and consequently, despite the relatively poor audience turn-out (as, sadly, is to be expected), that it was an enterprise of some importance. Thus, the short essay entitled ‘Wandelweiser and Improvisation’ (available in the PDF version of the programme

here) was subtitled ‘The Dangers of Reverence’, and the programme’s placing on the church seats as a kind of hymn-book parodied that ‘reverence,’ even as the essay itself thoughtfully considered the importance that reverence, restraint, and a quietness of communal attention (qualities perhaps associated with certain forms of religious experience, church-based or not) might possess. Pinnell’s points with regard to the drawing in of audience as active participants in

listening, and the restraint of improvisational excess through compositional framework that yet, in its looseness, also restricts the ego-mania of a controlling composer figure, are ones very close to the way that my own thinking has developed on this topic. In relation to this, if the sparse audience was spread out through the church, rather than banded together in close or obviously communal quarters, and if many of them might have had their eyes closed for at least half of the music, that was the result of a feeling of ease and comfort within the surroundings – not the comfort of complacency or an unproblematic wallowing in beauty, but, as Pinnell again notes, a mood or mode of listening that may also be fraught with tension, the mechanics of close mental attention, and, to me at least, in the composed pieces by Jürg Frey and Radu Malfatti that made up around half the concert, feelings of austere yet wrenching melancholy and sadness.

Sarah Hughes and Kostis Kilymis are, as a duo, perhaps something of an unknown quantity – this was, I believe, only their second public appearance in this configuration (I’m sure they’ll correct me if I’m wrong). Though they appear as part of a quartet with Patrick Farmer and Stephen Cornford on the Another Timbre release ‘No Islands’, and are both involved in the running of improvised music labels – respectively, Compost and Height (co-run by Hughes and Farmer) and Organized Music from Thessaloniki – their presence as improvising musicians is less established, and one gets the sense that their work is at a stage of development perhaps further back than that of, say, the ever-present and enormously experienced Lash, or of Angharad Davies. I think, though, that this is precisely what made their set of interest, for me – its sometimes hesitant reticence, the logics or non-logics of its unfolding rough-edged in non-predictable ways that didn’t always seem intentional or even, quite, to work, but which roused the listening ear out of slumber and into a focussed following of trajectories and pathways taken or not taken.

I’m not sure if this is exactly the way to phrase it, but there was a simultaneous sense of the musicians being both rigorously in control, and of suddenly, and unexpectedly, having the rug pulled out from under their feet – after a long section in which Hughes rhythmically rubbed a bow up and down the side of the zither, she abruptly stopped to leave both musicians suddenly silent and sitting still, as if the performance was about to end. There followed a few seconds, not quite silent, in which Hughes might either have been performatively packing up, or continuing the musical endeavour, as she began removing mini clothes pegs which she had previously attached, as preparations, to the zither strings. It was a while before continuity re-asserted itself, before we were sure that the performance was definitely still under way -- and perhaps this is what I find valuable, and rare, in a mode of music-making, that, despite its methodological openness to and embracing of risk, all too easily falls into established pattern: that moment of uncertainty, the truly improvised moment, where one’s every move, one’s every gesture, will have a bearing on the course, the success or failure, of that particular section, even of the piece as a whole (for once a thread is lost, it’s hard to pick up again).

Kilymis’ electronic set-up was seemingly more capacious than Hughes’ simple amplified zither, consisting as it did of what appeared to be a couple of fans or motors, a selection of pedals, and a no-input mixing board, yet if anything he was the more reticent of the pair, seemingly hardly to touch much of the equipment on his desk. Indeed, at times he made Hughes seem almost busily active, note following note in, if not rapid succession, then enough speed to form what might be described as semi-melodic shapes – though her occasional exploration of the gentle, harp-like thrum of a plucked open string was reined in enough to avoid seeming merely ‘atmospheric.’ Similarly, while drones (with their propensity to fill, or to alter the space) are a fairly stable and staple element of much music of this kind, the pair tended to avoid such fixed stretches, with only one section provoking the imperceptibly slow head nod accompanying such sustained aural washes. The set ended with the barest continuing tick, left running without intervention by Kilymis – he, Hughes, we the audience, all sitting listening there to the machines’ insect heart, beating just within audible range. Here one might recall the paragraph from Pinnell’s essay in which he comments on the way in which the audience are drawn in as participants in a close listening of the kind required from, and demanded by and of, the musicians themselves. Whereas in the composed, or semi-composed music of the Wandelweiser Group, this implies a participation in structural process – anticipating, working out, revelling in the at least partially pre-determined manner in which a piece unfolds – in the case of Kilymis’ and Hughes’ improvised performance, it also seemed to mean a kind of detachment from the act of producing sounds themselves, the occasional moment – such as that ending – in which the musicians seemed as removed from, or puzzled by what was being heard as the audience. I am certainly over-egging the rhetorical pudding here: all the way through, the duo were making active decisions, thinking hard about what to play – witness Kilymis’ frequent half-glances up at the audience – even if Hughes’ demeanour can at times seem casual-tense, as if she were simply playing in private, displaying a certain un-weightiness of gesture. But I do want to stress the way in which, not only in this duo set, the collective sound that is created is a genuine collaboration between those who make it and those who experience it, the two indeed crossing over at points: to

hear the music is indeed to

sound it in a particular way, to allow it the space to breathe or to be itself. It is not only about the way the music sounds, but about how

you sound, to paraphrase Amiri Baraka – how you sound, and how the venue sounds, or allows sounds to be heard, how everything in that situation sounds and is sounded, whether through the smallest bowed whisp or whisper on the zither, or through the generation of an almost ecstatic sleep strum through the tiniest of tinnitus tones, whether through the gurgle of a stomach, the compressed hiss of steady breathing, or the muffled sounds of the quiet city outside.

Following that opening set, Jürg Frey’s ‘Time, Intent, Memory’, a piece composed especially for the concert and performed by the full sextet of Hughes, Kilymis, Dominic Lash, Angharad Davies, Radu Malfatti and Frey himself. If Wandelweiser music is often thought of as austere or minimal in the extreme – Radu Malfatti’s more stripped-down, smaller ensemble work, Manfred Werder’s gnomic text instructions –Frey’s pieces seem somehow fuller, despite their similar economy of means; seem to distill certain harmonic aspects of twentieth-century classical music to a transformed essence, like drops wrung out of a cloth, exploring the simplest of harmonic or rhythm notions and worrying away at those single ideas, through repetition and incremental transformation (in the tradition of minimalism, of course), through an unashamed delight in the creation of beautiful sound – even as that sound, to the non-initiated, may seem to embrace, or at least not to shy away from, the occasional harshness or clash, discord not refused for imposed blandness of total accord. The notion of a whole tradition of music stripped down or back to a shorn, ghost-canvas is, of course, not an unfamiliar one – I’m thinking of pieces I’ve recently witnessed by Helmut Lachenmann and Luigi Nono; of Luciano Berio’s (in)completion of an unfinished Schubert manuscript, ‘Rendering’; and also of the ghost-romantic music of Russian composers such as Valentin Silvestrov. And for sure it’s there in dub and dub-step, in hip-hop’s stretching out over fragments and shards from records that sound out of the past, whether in celebrated nostalgia or détourned, mocking irony. Yet Frey’s filtration of musical history – the intense accumulation and concentration found in a single note, a single chord; indeed, the ‘time, intent, memory’ packed within it – would seem less overtly to present itself as a dialogue with, or haunting by the past; even as elements go back to the very basics of folk traditions – the sounding of particular drone-based formations, the ‘imperfection’ of a sounded tone – even as there always seems a read-in referentiality to each sound and silence (there are times when a melody spins off in my head as I listen, a line taken for a walk from the single point which in actuality is being sounded at that moment). Indeed, it is these very points of ‘referentiality’, or suggestiveness, that are also the most purely moving or beautiful parts of the music (no need here, I think, for scare-quotes around those words).

Despite its conceptual-philosophical title, then, the piece heard tonight had its impact primarily through subdued, non-manipulative emotional pull, centring, or so it seemed to me at least, around a mournful melodic phrase that was broken, or extended, in, round and with silence. Ensemble as unison, clear lines in simple harmonizing. Pick up and echo, like lines starting and stopping at different points on canvas blankness. Instrumental timbre in echo, Malfatti’s trombone, Lash’s sonorously low bass, Hughes and Kilymis held e-bow’d and electronic tones in background merge, Davies and Frey the melodic movers, Frey’s clarinet here by far the most silvery, straightforwardly beautiful of all the sounds. A pigeon, coos (on the roof?). Laughter, dimmed, passing. Bruno Guastalla’s breathing, 2nd row. The scratch of my pen nib, writing this. Violins’ held note in waver. Malfatti, a trombone sound so soft it seems sub even the distant traffic rumble, granite strings and clarinet in, now the cavernous effect of Malfatti’s muted instrument, almost but not quite beating frequencies, the ensemble texture not ‘doomy’ exactly, nor serene (two default modes for much minimal experimental music these days), but its measure is grave and slow and sad. Simon Reynell’s extended stomach whistle.

The piece’s formal architecture, as it appears on first experience: two notes, generally, sounded by clarinet or violin, then other instruments coming in, it overlaps, goes on, with breathing sections, say one minute of silence (waiting / pause / rest) in between. Davies’ trembled high string and Frey’s clarinet in desolate throatache, clarinet call, those low moans, not loquacious enough for song, tho it’s all

contained, formal, is

not inarticulacy. Yet at times this is what it seems, constantly reaching towards, failing to reach, starting back at the beginning again to reach towards, full articulacy, loquacity – towards that ‘gabbiness’, perhaps, that Radu Malfatti so descries. Put it another way: this is saying the same statement over and over, beginning it again, reiterating or -writing, or -scribing or –speaking, it; for a point of comparison, think maybe those repeating parallel elements in Charles Ives’ ‘The Unanswered Question’, as referenced in Evan-Maria Houben’s ‘Druids and Questions’ – the questions those pieces raise with regard to time / memory / change. It take time to iterate. Yet it’s all done, set out, transparent, pretty much on first statement. That simultaneous clarity and complexity of idea, intent. Or in passing those acoustic effect / events / coincidences ‘exterior’ to the music (of course, as any one with even the most fleeting acquaintance with Wandelweiser knows, nothing in the environment can really be ‘exterior’ to the music, the music expanding out to capaciously include that environment, however fragile and easily-disturbed such a balance or encompassing might in experienced actuality be). The church bell sounding the hour, first as background tintinnabulation, in the ensemble spread out, then as an explicit reminder of passing time, punching out the seconds as punctuation to silence, Frey acknowledging its explicitness and appropriateness with a little smile. And now his breath clarinet becoming a dialogue with it, a counterpoint, held ground / extension set against the small sounds of repetition, repeated. The ensemble sets out now what seems almost a resolution-chord, with sorrow still imbued, and still the bell, tolls.

A third page of the score, collectively turned. Rustle. More space fragmented melodic in what seems to be a recontextualisation of previous material from the other sections of the piece. Ending with the most amazing ensemble chord in granite contour, like the sound you hear as all slips out, the final mourning song or breath for the end of the world, and the most intense silence after, probably shorter than it seemed, inhabited and filled by the swelling, receding ghost of that chord, afterglow swims over horizon, sinks. Clap clap.

Afterwards I discover the actual formal structure of the piece, beyond speculative or effusive conjecture. Chords and pitches are all written out, individual notes placed in columns, over several pages, with chords at the bottom of those pages, yet each musician is allowed to make their way through the score at their own pace, at a vaguely-agreed root temp of 40bpm. Thus the previously noted overlapping of lines, and thus the fact that any unison that occurs is the result of simultaneous decisions made by different musicians: ensemble as the collectively-decided and negotiated sounding together of separate lines, rather than imposed, homogenous mass. The restraint of this particular group of musicians, their un-showy, un-fussy approach to the score, is thus central to its successful rendition: one must pay attention to the way in which one realizes the piece, one cannot simply play the notes on the page, safe in the full indications of the composer’s pre-decisions. This is not, however, merely an opportunity for each individual to stamp the muddy foot-prints of their own ego all over the shop: and that this sextet was not in the least concerned with such manoeuvres might be indicated by the fact that all members of the group were given the possibility of playing short (notated) solos, and yet only Frey and Lash played theirs – the latter ending with a resonant thrummed pluck that, for the briefest moment, seemed to summon the ghost of Jimmy Garrison into the church.

A second improvised duo to follow: the combined strings of Lash and of Angharad Davies, Davies, sawed bowing motion in slip-string control (in which the sounds hover around a general field of semi-pitched timbre, but with numerous delicate variations around the edges), rubber-banded string pluck, just one or two notes placed exactly in almost-tandem with Lash’s bow-on-bass-body-rub, wood scritch and scratch. The most exquisite quietness at times, but also, particularly in Lash’s playing, a more obviously reactive ‘improv’ impulse (though one might ask, what was the echo / unison of lines in the Frey piece if not reactive, albeit in a different, more obviously restrained way?) – the result, it would seem from subsequent conversation, of a deliberate attempt not to play a ‘Wandelweiser-style’ improv, while remaining within the spirit of the event as a whole and keeping the gab in check.

Finally, an interval preparing us for the concert’s closing piece: Radu Malfatti’s ‘Darenootodesuka’, the title a Japanese phrase meaning ‘whose sound is it?’ (perhaps a quotation from that important Malfatti collaborator Taku Sugimoto?), the ramifications with regard to the ‘ownership’ of sounds, the fostering of collectivity, the activity of listeners and of environment elevated alongside the activity of musicians, and so on, already discussed at various points above. As in the Frey, mutating ensemble chords seemed to be ‘lead’, or pre-empted, by Davies’ violin. At first, the silences that had permeated ‘Time, Intent, Memory’ were largely absent, continuity not felt as pulse, but gradually changing organic drone, Frey’s clarinet meshing with Hughes’ e-bow’d zither and Kilymis’ laptop, Malfatti and Lash low-blending, Davies again alternating two or so desolate notes, more, an entire tone row, as melody, ascending and descending the stave in simple figure; simple, again, a limited actual number of notes, but in varied combinations, re-iterations, permutations; and again this interest in mournful almost-melody, in the

sound of the ensemble, its timbre, its textures, and in the relation of parts together but in parallel not-quite unison, overlapping rather than entirely coinciding. Like the Frey, perhaps even more so, it was quietly devastating at times, as darkness outside the church in dark blue falling. The first section, 12 minutes – for the first eleven of these, each musician playing the melody one to five times, with breaks in between, then sounding, in the final minute, an ensemble chord; a timed silence; section two. Once held note. Shorter silence. Now Lash leading, others coming in. Frey and Davies, held notes with patient semitone descent, each voice stating the melody again descent and over, taking it up, holding, leaving. (Club-bass-boom from outside pub creeps in as brief minor disturbance. After the concert was over, as everyone left, an off-key karaoke rendition of ‘My Way’ spilling out of the door.) Simplicity of the materials, their patient not-elaboration, not-development, not-‘unfolding’ (as that word implies the other two), making the statement in the time it needs, over and over, in ensemble repeating, turning up then down and not leaving, descending and rising and not leaving. The ground, pitched together drifting apart and back, how long can a voice hold (a note), instrument in wood and breath, electronic, each part heard and distinct and together ensemble announcing, constituting, not with tension fraught as slow emerging – always emergent, always there, in that initial transparency revealing, and then revealing, and revealing, in material re-sounding, lay this out and you hear it, it’s not a complexity game, you

can contain the information, here, in your hand, in your head, in your ear, it’s on the surface, you’re in the surface. The descent / ascent as it whoosh-slides with the laptop sine // in the surface rocking, maybe, sadly cradled, or quite still, breath and closed eye // the lowing of Malfatti’s trombone, as if in hollows and mists muted, veiled. Longish silence // the unison sound, refreshed, shortly sounded, slight silence, almost, not quite silent, still the air resounding, stating chord as knell, as almost spoken utterance, twice, of one word. Silence. Again ensemble, differing (not violin (now violin. The descending part of the melody again in play // longish section of all that again. In cycles, encycled, the line, the tail spins on itself it turns, the trail encircling, encircled. And utterance stops. It starts. In continuum, holding, just overlap morphing. In silence it stops. Again it starts. The musicians, had paused, put down, now take up their instruments. The sound is new each time the pause – the full silence – refreshes. “do i cease to exist in between waves of sound?” (The rhetorical question, from Francis Brown, appended to the CD release of a previous performance of this composition, on Malfatti’s B-Boim Records). The answer is no. Again shortly stated. And ending, the piece, on that tail whisper. The echoed fragment as final reminder, cut statement, stated, end. Fading with the darkness. Intensity. The scores’ instruction: to play each note as if finding it for the first time. ‘Rather timidly’. All sounds calm and very quiet. Might one not recall here Miles Davis’ instructions to John McLaughlin during the recording of ‘In a Silent Way’: “Play as if you don’t know how to play guitar”?

“do i cease to exist in between waves of sound?” I do not cease to exist but my existence is altered by those between-states, as it is altered by those waves of sound. ‘Between’, that word inevitably now recalling the 2006 Rowe / Nakamura collaboration on Erstwhile. In other definitions: ‘in the space separating’ // ‘in portions for each’ // ‘among.’ What it is between is between individuals, between notes, between audience and performer, between both groups and between the sounded and sounding environment: the points are dual, it is dialogue, to be between things there must be two, or more – multiple, ensemble.