Paul Shearsmith and KMAT performing at the Hundred Years Gallery in 2012.

Trumpeter Paul Shearsmith passed away a few days ago in Stuttgart, aged 78. One of those many presences on the UK free improvisation scene known to—and as—one of the faithful—his German Wikipedia page is extensive, his English Wikipedia page non-existent. So is cultural memory.

Shearsmith grew up in Tadcaster, Yorkshire, where his father was the local blacksmith. Influenced, in his words, by the BBC Sound Effects library, on leaving the Leeds School of Architecture and moving to London, he attended jazz gigs by Stan Tracey. Here, as he tells it, he would stage a weekly heckle. On the basis of this, he was invited by drummer John Stevens to attend his workshops, playing a battered pocket trumpet he’d bought second hand with Stevens and the Spontaneous Music Ensemble and with the London Musicians Collective at the Little Theatre Club in the West End and at the ICA back in the 1970s.

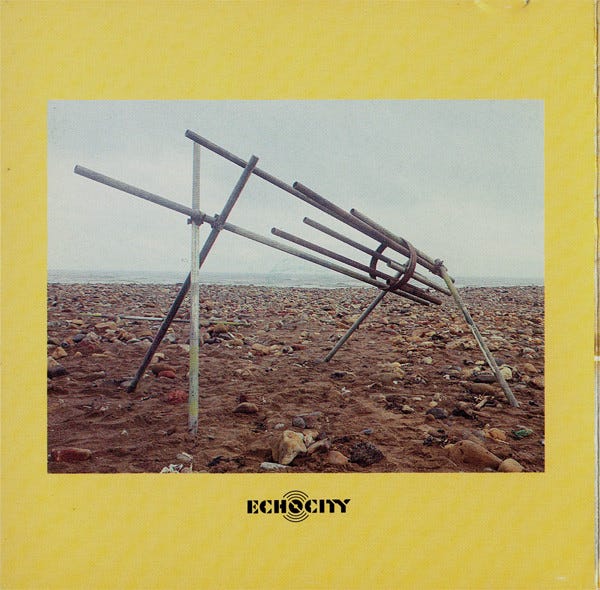

In the early ’80s, he travelled to Indonesia, where he came back with a ‘trompet’, a children’s instrument made from film canisters, a plastic tube, and a reed made from a balloon. Adapting this with a garden hose pipe as the ‘baliphone’, he met instrument-builder David Sawyer and through him joined the collaborative group Echo City with Guy Evans, Giles Leaman, Julia Farrington, Rob Mills, and Giles Perring. Starting in 1983 with a playground in Weaver’s Field in the East End, dubbed by the NME an ‘urban gamelan’, the group built what they called ‘sonic playgrounds,’ inventing tuned percussion instruments, made from old piping and other industrial and storage implements, including ‘batphones’, ‘fibrephones’ and ‘barrel drums’, and running workshops across the UK, Europe, East Asia and North America, including a collaboration with members of the Sun Ra Arkestra on the beach in the Isle of Jura, off the coast of Scotland. In Echo City’s work, music becomes sculpture, part of a public place and a participatory aesthetic. This is not about gigs or records, though they are a part of it, but about a more ongoing and more genuinely collective process. As Shearsmith put it: “I believe music belongs to everybody and can be made by anyone. Don’t let technique get in the way”.

These kind of public projects have always been a key part of UK improv, and, whether in Echo City or elsewhere, it was the spirit of collective playing that informed Shearsmith’s work, from his early work with Stevens to Maggie Nicols’s The Gathering, playing in the groups the Funking Poets and APE with the likes of saxophonist Big Mike Walter and poet Grassy Noel (for the latter, Shearsmith added fire extinguishers to his instrumental arsenal), or in the duo The Fujii with Japanese singer-guitarist, Koichi ‘Fuji’ Fujishima, who he met while the latter was busing in York, and latterly, with Ben Watson’s freewheeling AMM all stars.

Over the years, Shearsmith worked in an architecture firm, practiced photography, turned his car into a work of sculpture, played trombone, tubing, “tuned gas main”, and the baliphone in addition to his trusty pocket trumpet. Back in the day, I played in private a few times with Paul and the other members of KMAT, his trio with guitarist Keisuke Matsui and bassist Graham Makeachan, indefatigable host at the Hundred Years Gallery in Hoxton, where Shearsmith was a regular. It was soon after the election that saw Boris Johnson elected mayor of London: Shearsmith, he reported, had been playing in Ken Livingstone’s “battle bus”, blasting out socialist classics like ‘The Red Flag’. Around that time I remember anti-austerity protests, the student movement, the carnivalesque energies around the Hundred Years and its constellations, a warehouse near King’s Cross with a variant on Henry Threadgill’s Hubkaphone made out of old storage canisters for reels of film, a parade with bells through the streets of Hoxton organized by Mary Lemley in memory of Gabriel Hardisty-Miller, running into Grassy Noel going the other way up the street on a protest where, suddenly, everyone was going joyfully in every direction at once, and the street briefly reconfigured itself, as on protests it does, lines of poems, lines of music that refused to line up or be counted, out of time. And Paul Shearsmith’s pocket trumpet, piquant and strong in the wake of Don Cherry, blowing out little blasts of light.

Free improvisation in the UK and elsewhere developed as a social music and in this often unheralded way it continues, in venues like Hundred Years, the late lamented Iklectik, or the slightly more publicly-visible scene around Cafe Oto. It’s a music that's often politically connected to the traditions of left wing politics that have for decades been under steady attack from both the Right and the Labour party in its Blairite or Starmerite configurations: as well as the Livingstone Battle Bus, Shearsmith recorded an Iraq war protest song, and the Hundred Years Gallery has recently been raising money for the people of Gaza. Heard by small audiences, the music is not ‘popular’ by record industry terms—or the kinds of ‘focus groups’ by which Starmerite lurches to the right are justified—but it is more fundamentally than that a people’s music, one that, because it does not make money and is barely tied to market demands, aims at exploring only itself and its world, that draws, in spirit and sometimes in letter, on the traditions of protest in folk musics of various kinds, in free jazz, in experimental theatre or film and in the various experimental incarnations grouped under the headings of prog-rock or (post-)punk (Guy Evans of Van der Graaf Generator and Susie Honeyman of the Mekons both played in Echo City). The music stages a counter-history and a different way of being to all the various lies and erasures of memory surrounding it.

That was the world Paul Shearsmith believed in. That was the music that Paul Shearsmith made.

3 comments:

A man full of passion, British wit, an open mind and a huge heart! We will miss Paul a lot.. 🥲❤️🚙

paul was into sport especially cricket, rugby league and squash.The latter at the hornsey club where he represented the club with plenty of energy and enjoyed the few pints after. He will be missed by Jim,Des, Simon,Sean and many others including myself as an interesting and friendly guy. John Linden

was just posting about how to create a tuned 'bali-phone' when I discovered that the person who turned me onto this instrument, Paul Shearsmith passed away in March of this past year.

It's my birthday suddenly, but I am gutted! Paul had an enormous influence on me. My wife and I met him and his lovely and talented musician wife, Bettina or 'Betti' in London on my first appearance at the very first live looping event in London.

Post a Comment