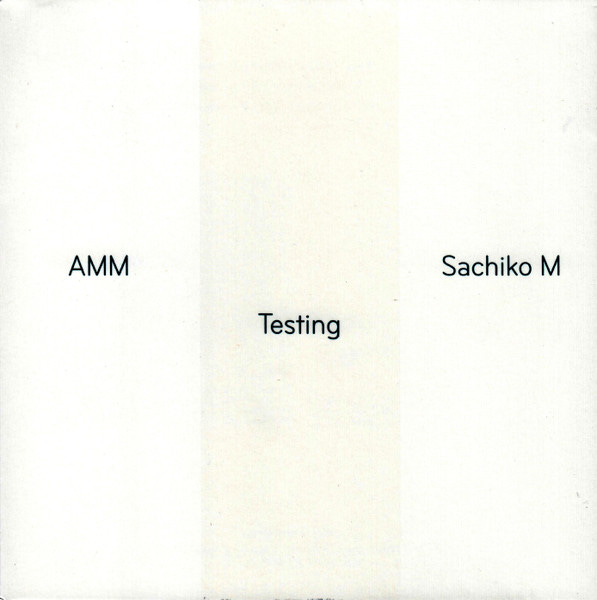

Mid-December 2004. The Museum of Garden History, Lambeth. AMM—Eddie Prévost on percussion and John Tilbury on piano—perform with Sachiko M on empty sampler, a performance a little over an hour long, unearthed from Tilbury’s archive and released in 2025 as Testing. (The album is available from the Matchless Recordings website here.) We begin with a duet for sine wave and the rumble of muffled traffic familiar around old buildings in London, the stone and the earth vibrating with vehicles unknown when they were built. Collisions of time.

Today as I put the CD on, I have floaters in my eyes, and trying to focus them sideways on a point in the distance as you’re meant to, things start to blur and swim in the middle in the field of vision. The start of the music something like that, too. It’s several minutes before we hear a tone from the piano, the overtonal ping of a note with the string dampened by finger or object. Bending, pressing and holding the piano’s inner strings, varieties of pressure and weight can lead to the subtlest shards of resonance intended and unintended. Tilbury has been working this area for decades and each note is inflected with the history of that practice: a practice of instantaneous carefulness, patience and intense listening. Prévost’s cymbals and tam-tam are invariably bowed: percussion reinvented as bowing rather than striking, a sound sustained by an incessant movement of the arms, but not a traditionally rhythmic one. Percussion becomes a stringed instrument and the piano a kind of muffled, tuned percussion played quietly and slowly. Machines are turned against themselves, identities swap and blur.

A sudden and exquisite arpeggiated chord. Broken and rolled, the piano as harp. The snows started to melt yesterday and the temperature today leapt up by around ten degrees. The world outside the window, muffled for a month in the snow, suddenly comes to life again, and sounds from outside mingle with the performance, so I can’t tell if the birds or church bells I’m hearing are coming from the recording or from the newly-brightened daytime outside. There’s a particular quality of hush to this recording, as if the implacable harshness of Sachiko M’s test tones, buoyed on the feather down of bowed or struck piano string and metal were a kind of austere cocoon, a drained lullaby suffused with a mourning attentiveness. The scrape of percussion is like a rusted gate, a door, the piano’s ping a gentle tap. Gaining admission, quietly exiting. At one point a police siren; at another, the choked utterance of what sounds like a sampled voice; at another, a sound as if someone were quietly whistling to the side. Seymour Wright’s liner notes link the music to plant growth, to the plant cultivation in the museum’s history, to dissociative fugue states, where one temporarily loses all sense of who one is or where one is. (As Alessandro Giustiano puts it, Sachiko’s sounds (for the most part) involve “no attack, do not offer mediation or guidance.”) And yet both Sachiko M and AMM have never sounded more like themselves, a practice of identity as dissolution.

Prévost plays a “stringed barrel drum”, a wine barrel he took from an old Italian restaurant on the Strand where AMM used to eat and repurposed into an instrument. With its added strings, it sounds somewhere between a guitar, a koto, and a lute; the upper end of a string bass, and the sound one gets from stringing rubber bands over a box to make a child’s guitar; a delicacy chunky and crude, answered by Sachiko M’s electronic rumble, crackle. Music as salvage: the empty sampler, the empty barrel, the piano, its interior treated, as per Annea Lockwood burning or flowering pianos, as a source of endlessly modified growth, of resonators and resonating devices, string and hammer and key, a finger or an object added and taking away. At once clear and always blurring the edges, the music seeps in like the cold Wright describes on that night, seeping in from the Thames and its tides, sweeping in from the outside, bleeding into skin and stone. Like plants, musicians, too, have to weather the winter: often in freezing venues, wherever can be rented or found, to prepare, to test, to take and transform the place they’re in in the gentlest of ebbs and flows, of incremental growths, of giving and taking.

Stuart Broomer in his review talks of the music’s opening as “a study in the ineffable”. But this is also a study in the palpable. It is about presence, however stretched or suspended. Sounds that die and are succeeded by others. AMM’s second album was, after all, called The Crypt, and in their repurposed industrial sounds they perhaps refract something of the musician’s pasts, already haunted: the echoic clang of the factory, the sounds of metal striking, sparks flying, ships hauling into docks where Prévost’s grandfather worked, the post-war damage in London and other cities. In 2015, AMM performed at the Museu Industrial de Bala do Tejo in Portugal, a performance later released as Indústria. And as AMM’s music continued through the 1980s and out the other side, those characteristic sounds, their boom and swell and crackle, had come to speak all the more of the post-industrial wastelands left in Thatcher’s wake. (On the other side of the ocean, Detroit techno: both creative responses to ongoing conditions of production.) The histories, like those of the Museum of Garden History and other spaces in which AMM have performed, could be traced back even further. You might even go as far back as Prévost’s Huguenot ancestors, fleeing persecution in France. The Huguenot exodus gave the English language its word ‘refugee’, from the French réfugié ‘gone in search of refuge’: the kind of history all too easily forgotten in the current anti-migrant hostility seeded in Britain and across Europe.

The music is not “about” any of these things. Yet they surround it, are the world in which it moves. Presence stretched, suspended; sounds die and are succeeded by others. Yet in that moment of sustain—piano pedal, sampler’s infinite spread, the way a bow stroke maintains a static sound, paradoxically, through movement—and in their recorded after-life, they are never more alive.